When Second Homes Are a Primary Concern

When 14 men were arrested in a plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer in October 2020, most attention focused on the U.S. domestic extremism threat. The thwarted attack also highlighted public anger over health restrictions put in place for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Executive protection (EP) professionals, however, would have noticed another critical aspect of the case: upon concluding that the Michigan State House would prove a difficult target, the conspirators planned to kidnap Whitmer either at her personal vacation home or at the Michigan Governor’s Summer Residence on Mackinac Island. In an audio recording of the planning, one of the culprits suggested that the group hire a realtor to find the exact address of Whitmer’s vacation home, then collect information on the surrounding area.

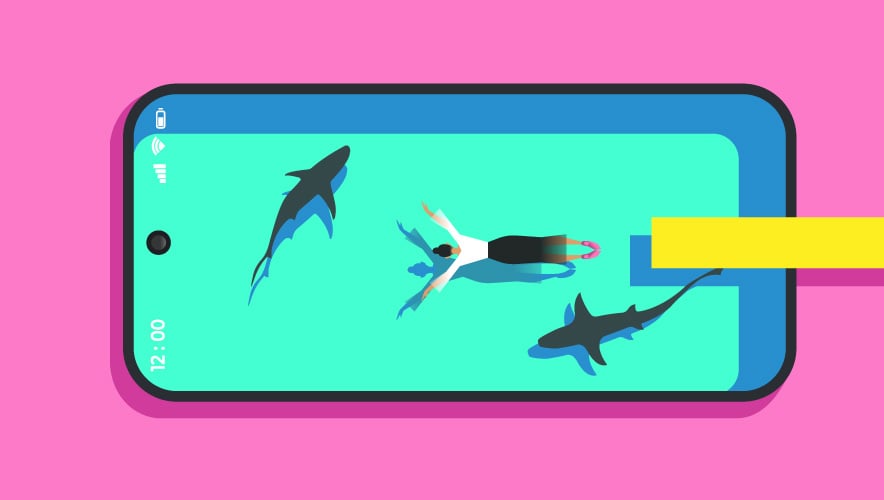

Second homes and vacation homes are supposed to be sanctuaries, and the people who decamp there usually treat it as such. But public figures, corporate executives, and high-net-worth individuals who own these properties often neglect the essentials of executive protection that they practice in their offices, on official travel, or in their primary abodes.

“At times, CEOs let their guard down when vacationing or staying at their second residence. They sometimes forget that ‘risk travels’ and have a tendency to expose themselves unnecessarily to these risks,” says former Boeing CSO Dave Komendat, whose range of responsibilities included EP.

The would-be Michigan kidnappers understood that. This article offers advice on how a corporate security department or executive protection team can help make these places of refuge both rejuvenating and safe for clients.

At times, CEOs let their guard down when vacationing or staying at their second residence.

The COVID-19 Effect

The COVID-19 pandemic that may have triggered the Michigan State House plotters also shifted the EP landscape. Corporate executives, Hollywood actors, tech millionaires, investment bankers, day traders, professional athletes, and anyone else who could afford to flee crowded areas flocked to remote—yet Internet friendly—locations such as Big Sky, Montana; the Catskill Mountains in New York; Sun Valley, Idaho; Bar Harbor, Maine; Turks and Caicos, Barbados; and Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

This exodus had two major impacts on EP. First, security directors, agents, and GSOC staff found themselves in the dark about their executives’ living arrangements. In many cases, they were unfamiliar with the properties and had to scramble to conduct assessments and to identify gaps and risks at the property, in the neighborhood, along transportation routes, and elsewhere.

Second, locals sometimes viewed these arrivals as an invasion of the elite, which could raise prices, drain local resources, and disrupt life in the community. Irked residents could themselves pose a threat. In fact, Londoners who escaped to seaside residences during the height of the pandemic received threatening messages from locals.

SponsoredInside the Shadows of Alt-Tech Social Networks: The New Haven for Threats Against ExecutivesIn recent years, criminals and fringe groups have started moving to a growing collection of “alt-tech” social networks. And as a result, these communities have become breeding grounds for doxxings, false rumors, and violent extremists – posing a serious risk to executives and high-ranking employees. So how do protectors respond to this threat? |

Risk Assessment

An EP program should start with a standard risk assessment, including risk identification, analysis, evaluation, and prioritization. The following topics represent a good start for an assessment, but protection professionals should tailor questions and dig deeper depending on the details specific to the employer, principal, and location.

The local lowdown. Protective teams should access data on crime, hot spots, and trends, and ascertain the area’s threat profile. They should also assess other factors specific to the neighborhood, town, region, or country. For example, what is the physical geography and topography? Is the home on the seaside, on a mountaintop, in a city, or on a flood plain? Security preparation and response could vary significantly based on those physical features.

In one case with which the authors were involved, a few months into the COVID-19 shutdown an executive purchased an additional home in a rush private sale, sight unseen except for some photos. The home was in a rural area in a different state than his primary residence. With winter came a storm, and the home suffered major water damage. The executive learned that the house was in a flood zone, which the seller had failed to disclose. The security team responded by evacuating the executive, finding him new accommodations, and providing protection at his temporary quarters.

Dealing with the fallout took the executive away from what could have been ample productive time for the employers, says longtime executive protection specialist and trainer Bob Oatman, CPP. Oatman stresses that facilitation of everyday tasks, allowing executives to get more done for the business, is a major component of EP duties.

In addition, EP specialists should familiarize themselves with the local culture, the different dialects or languages spoken there, and the politics of the region. In another move that occurred during COVID-19, an executive purchased a home and the neighboring property in another country, but he didn’t fully understand the culture of his new town. He planned to tear down the existing house and build an enormous mansion with pool, tennis courts, and other amenities.

Many residents opposed the construction of large houses and the presence of “big money” in the area. When activists learned of the executive’s plans, they protested and sabotaged the construction. In response, two members of the EP team moved into the residence to secure the construction site while the executive remained in his home country. As it turned out, the executive donated generously to the community, the antagonism dissipated, and residents accepted the construction.

It is likewise critical to be familiar with local laws, regulations, and ordinances. Executives could run afoul of the law and gain unwanted attention through a seemingly innocuous action such as using a yard sprinkler while water use limits are in place.

Another, often neglected, aspect of a threat assessment is to ascertain the local perception of principals, their families and friends, the principal’s employer, and the employer’s product or service, Komendat says. British royals Prince William and Princess Kate had to scuttle a trip to Belize in 2022 when their plans aroused a debate about the UK’s colonial legacy.

The very presence of ultra-wealthy people in rural areas might also inspire pushback. Celebrities such as Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel were blasted for riding out COVID-19 in a luxurious community where the local medical infrastructure couldn’t tolerate a significant influx of patients.

The presence, proximity, response, reliability, and trustworthiness of emergency services are another critical consideration. That includes law enforcement, fire services, and emergency medical care. Additional private security resources may be required as well, such as camera repair, so their availability deserves thought.

Cyber considerations. EP professionals sometimes overlook the cyber aspect of residential protection. Areas to review may include any online views of the principal’s property, such as on Google Maps or realtor sites, as well as information about the home’s location, such as address, photographs of the house, and social media posts by companies or individuals that have provided services at the residence.

If executives wish to feature their home in an architectural publication or the like, security should urge them to insist on confidentiality. Not only should the owners not be identified, but the publication should also offer only minimal, general information about them. The publication, photographers, writers, and editors should be asked to sign nondisclosure or confidentiality agreements.

Residents. The heart of executive protection, of course, is physically protecting the principal and his or her family, staff, guests, and entourage. The security team should research the public profile of the principal and family, including publicly available views, opinions, positions, donations, investments, and so on.

Social media also merits attention. While security may want to limit the family’s posts on social media, that may be an important method of communication for the family or organization. No one is going to stop Elon Musk from tweeting, for example, though many executives and families would benefit from learning the consequences of posting and the basics of good cyber hygiene.

Protective Measures

Once a risk assessment has been conducted, appropriate measures can be put in place. The basics of physical security include perimeter protection–such as gates, fences, sensors, and cameras—as well as alarm systems, doors and locks, and video surveillance.

Cameras must be adequate to the task they are performing (e.g. low-light for outdoors nighttime use, sufficient resolution for identification). Both principal and backup transmission methods should be considered, such as coax cable and Internet. Security should determine whether feeds will be monitored, by whom, how often, and where, as well as how data will be recorded, stored, and retained.

CPTED features can go a long way toward improving residential security. Landscaping, lighting, signage, and other tricks of the trade can discourage criminals and create witness opportunities.

The results of the risk assessment will inform the deployment of an EP team, along with the client’s lifestyle and risk appetite. Areas to cover include the number and gender of agents, their placement inside and outside the property, their specific hours duties, and the chain of command. If vehicle travel is necessary, plans should be made for advances, security drivers and close-protection details, and perhaps personnel in a following vehicle.

Agents should prepare for guests to the house, vetting them in advance if possible, Oatman says. This should include repair technicians, maintenance staff, party guests, postal carriers, and even children arriving for sleepovers or play dates.

A set of post orders or standard operating procedures should set expectations for the engagement and expected behaviors, Komendat adds. For example, the principal may want to keep a low profile or, alternatively, be seen in the company of overwhelming force.

Oatman, who has provided executive protection and trained thousands of EP professionals during a 40-year career, emphasizes that the privacy needs of clients heavily influence the protective posture. He was recently involved in a protection program for an entertainer who moved with her family to a temporary residence while doing a gig in a city known for its high crime rate.

Oatman’s team balanced the client’s desire for discretion–she had the agents sign nondisclosure agreements—with robust protection from street crime and other incidents. The protection team included professional security drivers who were highly familiar with the area, knew the safest routes, and liaised with police to identify potential trouble spots. Fluid communication was critical, especially by text messaging, to choreograph departure and arrival times. Key to the successful engagement, he says, was the initial introduction of the EP team to the entertainer and her family, which established trust, confidence, and compatibility.

SOPs should also dig into daily behaviors, such as expectations that the agents not bring peanuts or gluten into the residence because of a child’s medical condition. They should also set forth standards for interaction between the protection detail and the residents, such as never having weapons visible or using only specific appliances.

If the principal insists on a lower level of protection than the risk analysis calls for, the protection firm should consider turning down the contract. Inadequate or insufficiently vetted personnel can lead to trouble.

In a 2017 case, a partner at a prestigious Washington, D.C. law firm was shot during a home invasion while he was in a vacation villa in Turks and Caicos. Two intruders bypassed the alarm system and overpowered a single security guard to enter the villa. When authorities discovered the guard, he was “lightly bound” by his own shoelaces, raising the possibility of inside assistance.

Family and Other Guests

What happens when the principal isn’t on site, but family, friends, associates, or contractors are using the residence? The approach depends on a risk analysis.

While the principal owns the home, the employer has an interest in protecting its valuable assets (executives and their well-being, etc.) and reputation, even when the executive isn’t there. For example, an attack on a college friend who is staying in an executive’s home could lead to negative publicity and an economic hit for the company.

Most executive second homes should at least have alarms, cameras, sensors, and other systems that are monitored by the company’s GSOC. The presence and quantity of protective personnel—residential details, drivers, and EP agents—often results via an agreement between the principal and the employer. If the spouse and children of a highly visible executive are staying in the residence without the principal, they will almost certainly require a residential detail, drivers, and perhaps other EP agents. For the college friend using the house for the weekend, monitoring via the GSOC plus an overnight agent in a car outside the residence may suffice.

Don’t Forget

When setting up protection for a vacation home or secondary home, the following factors are often overlooked.

Ensure that an adequate infrastructure is in place for conducting business online and by cell phone, which requires robust high-speed Internet and cell service. While protection details often identify emergency responders, they may not check response times for those services. They may overlook contacts for emergency residential services involving outages or interruptions of electricity, heating and air conditioning, water supply, and plumbing. Disruptions in areas such as postal services, grocery delivery, and snowplowing should be planned for as well.

A common shortcoming in protecting second homes involves using security systems that do not integrate with or are incompatible with the system used at the primary residence. Having all properties on the same system is more efficient and secure, Komendat says. EP personnel should ensure that remote access to systems is available 24/7, including camera monitoring and recording, code changes to the alarm or access control systems, and alarm activation and deactivation. Camera placement should at least cover the perimeter of the house and project a reasonable distance away from the property. Interior cameras, if necessary, should be discussed with the principal.

Should a problem with a security system occur, it would be beneficial for security to have established a preexisting relationship with local security vendors. Such a relationship can be critical when, say, a power surge or flood creates high demand for the few security technicians in town.

Having all properties on the same system is more efficient and secure.

Similarly, EP staff shouldn’t forget to create relationships with local law enforcement. Komendat urges protective teams to physically meet with local officers to establish a rapport and to better understand what happens near the executive’s home. An existing relationship also facilitates an effective police response.

“I always stressed to our teams that they should meet the local watch commander or their equivalent as a courtesy and ask for help or insight,” Komendat says.

Some issues recur depending on the type and location of the property. For isolated homes, rodents gnawing on wiring can interfere with power and phone and Internet service. Local fauna can trigger motion sensors and produce false alarms. Homes along the coast are susceptible to hurricanes, moisture damage, erosion from salt, and even attackers from the sea. Owners of cold-weather mountain residences should anticipate impassable blizzards and perhaps snow melt and falling rocks. Agents should plan for emergency departures through such conditions as blizzards, floods, or mudslides.

Even sophisticated EP programs can be undone by simple mistakes or errors in communication. Protectees should have phone numbers for all the agents, who should make sure that their devices are charged. Agents should also always have phone numbers for the nearest police station, fire department, hospital, and ambulance service. And by no means should they post on social media during their engagement.

One of the most common mistakes involves lax controls. The authors are aware of many cases in which ex-employees and vendors retained access privileges well beyond what they required, sometimes for years. Principals often forget to change codes on doors, gates, and garages. Sometimes the code was even used by the previous homeowner.

Though attacks on secondary residences remain rare, they present a rare opportunity to breach an executive’s world when their guard is down. It’s up to EP practitioners to provide the protection that gives principals and their families sorely needed peace of mind and body.

Michael Gips, CPP, is the principal of the consulting firm Global Insights in Professional Security and a member of the Advisory Board of Cooke & Associates. Harry Arruda is the CEO of Cooke & Associates, a firm specializing in executive protection. He previously held senior global security positions with a life sciences company and a financial institution. Both authors are members of ASIS.