Q&A: Using Data

As the threat landscape has changed, security leaders have had to adapt. It is infinitely important that the leaders responsible for safety and security on university and healthcare campuses comprehend and strike a balance between needs versus wants as they build their programs to respond to changes. In this four-part Q&A, learn how four security leaders in healthcare and education tailor security programs and expectations using data, outreach, and partnerships.

←Introduction

Data collection is only one half of the puzzle. Now that we have the data we need, what do we do with it? In this section, Frank Spano, John Dailey, Bonnie Michelman, and Lisa Terry discuss converting data into actionable intelligence and balancing data against experiences, gut feelings, and organizational mind-sets or opinions to find middle ground.

After we get the data, how can we determine what we want to happen? What actions do we need to take?

Frank Spano: When compared with refined intelligence, raw data can often be overwhelming. Upon collection, data should be analyzed, confirmed, and applied in a way that advances the particular requirement. For example, simple statistical data that might satisfy reporting requirements under the Clery Act may prove insufficient for more complex evaluation such as internal institutional research or external accreditation review. As a result, one of the critical aspects of statistical data management is to have a solid understanding of the intended goal the data seeks to advance or support.

John Dailey: Once we have the data, sharing across the organization is important for transparency and solutions. Data is a living thing, and the mission or data creep begins when you don’t stay on top of it.

Not all data is created or used equally. For example, when compared to propped door alarms which are unique situational occurrences, data collected from card access—which is used for everything from access control to dining services and other on-campus purchases—provides fewer tangible data sets from a security perspective but much more relevant data sets from an operational perspective. Such information is usually tied to a specific individual and can be used for forensic or investigatory efforts, but they have limited applicability in identifying and responding to an immediate threat when compared to, say, a propped door alarm.

Bonnie Michelman: Analysis by the management team needs to be extensive to determine what services need to be augmented or eliminated, where resources many need to be moved, where additional training may be important in the organization and what security technology needs modification or enhancement. Procedures and policies may need to be created or adjusted based on data.

It is critical to share the data and its implications with the entire security staff (which often doesn’t happen) along with relevant departments so they can help be part of the solution. The danger is getting data that should drive a change or a new procedure and then not doing anything once the risk is known. Having routine meetings with a multidisciplinary group of colleagues to review the data and discuss modifications to operations makes this a formal and consistent expectation for everyone.

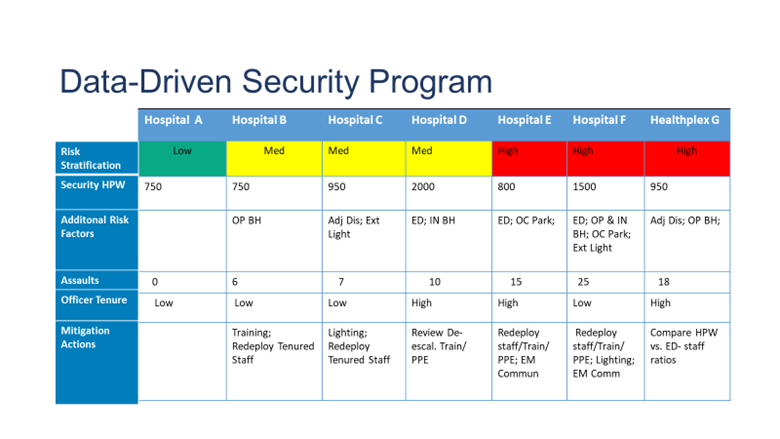

Lisa Terry: Developing a risk stratification model similar to the example that I have shared below (and based on a similar model from Katherine Eyestone and Shon Agard, MS, CHPA in the Journal of Protection Management) is very helpful is organizing and displaying the data and follow-up actions.

The green, yellow, and red colors are risk heat map colors based on CAP index scores. The HPW are the hours per week that security officers are physically on site at that location. The additional risk factors at each location include outpatient behavioral health unit located on-site; high adjusted discharges (high number of outpatient services); lack of exterior lighting; emergency department (ED); inpatient behavioral health unit; and off-campus parking for staff or patients. Reported assaults are important to note. Officer tenure can be important if turnover is high and appropriate training is not occurring. Mitigation and follow-up actions may then be deployed (and displayed), as necessary.

How can we balance the data we get with our experience, gut feelings, and organization mind-sets or opinions? How can we find middle ground?

Spano: Perhaps thankfully, technology still isn’t at the level where it can replace the inherent gut feeling that comes from decades of personal and professional experience interacting within and outside the campus community environment.

In everything from data analytics to on-ground community engagement and customer service, there is little doubt as to the continuing value of human interaction and experience as a critical component of tactical, operational, and strategic decision-making and application.

That said, there is a time for reliance on the gut feeling and a time for reliance on the data. Oftentimes, this is a combination of the two, and it provides an excellent platform to present and consider a series of potential solutions or outcomes. Trust your instincts, but verify through data.

Dailey: Data isn’t always going to match up perfectly. But when it doesn’t, we rely on subject matter expertise and professional opinions to guide the institution toward the truth.

Case in point, when we encounter potential data points that may not add up when reviewing Clery Act data, we rely on individuals who have advanced specific knowledge and training—to include our general counsel—to identify the proper course of action. We reinforce this through face-to-face meetings to review each and every potential Clery Act reportable.

The data is the data. What the institution is looking at us for is to anticipate next issues—issues created or enhanced by national or local events, as well as those arising within the campus community itself. In the security and law enforcement community, anticipating what’s next is somewhere between the gut feeling and our personal and professional experiences, which help guide our anticipatory actions. That said, we have to be careful not to adhere solely to those gut feelings at the detriment of paying attention to the information and intelligence we’re receiving. The data may lead us a different way, and we have to be open to that.

Michelman: Getting experiences and feelings from a credible number of multidisciplinary employees (and even patients) may help to navigate this balance with metrics and data that has been obtained. Surveys and risk assessments also help with this.

I think this question is important because data is a tool but not a perfect science. Getting the feelings and feedback from many may offer trends that are accurate and that data doesn’t achieve. Asking lots of questions of your security staff, frequently, and meeting with nurses, physicians, and those from other role groups to understand the climate and concerns will go a long way. This is also important for abating incorrect information that has become publicized or discussed and share accurate activity and response instead.