Context and Perception Matter in School Security

Violence in K-12 schools has altered both the perception and reality of the safety of the school environment. The human cost has been tragically high. But there is a forgotten victim in all this—the entire K-12 school system of the United States has been, to an extent, victimized by the incidents at Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, Oxford, Uvalde, and all the rest. School violence has fundamentally altered the modern K-12 experience in both the general perception of school safety and the operational reality of the school day.

School shootings are devastating, but thankfully, they are still quite rare. In the vernacular of emergency planning, they are “low frequency, high impact” events. But the 24-hour news cycle and the public dialog on social media both fixate on the worst incidents, which fosters intense scrutiny and, too often, a near-siege mentality for education professionals. Students, parents, educators, and security professionals are all struggling to come to grips with this altered reality.

From a security perspective, schools consist of three distinct yet deeply interconnected elements. First is the facility, including the buildings and its related “hard parts,” such as access control, doors, fences, locks, and video surveillance systems. Second is the operational platform. These are the policies, procedures, and common practices that define the ways a school functions. Last is the school community, including the students, staff, and parents. While the human element is where most security lapses occur, it is also people who must use the available tools and implement the processes effectively to make a school more secure. This has overwhelming implications for school climate and culture.

When school climate and culture are used in school security discussions, they generally refer to student supportive services, anti-bullying initiatives, behavioral threat assessments, and other student environment issues. But overall, school climate refers to the general feeling or perception by students and staff about the safety and security conditions in their school. This means that the climate and culture of a K-12 school has an enormous impact on both the perception and the operational reality of a school’s safety and security efforts. For a school community, perception is their reality, and that perception can either mirror reality or significantly clash with a school’s exposure and legitimate security conditions.

Consider the castles vs. prisons paradox. The buildings can appear quite similar, and even the physical security systems and practices can appear very much the same. It is their purpose that differentiates them. Prisons control dangerous people and keep their exposure to the community at large at a minimum. Castles protect their residents and assets, keeping nefarious individuals out.

Similarly, schools provide a safe and secure environment for the students and staff to facilitate the education of society’s most important asset. But do stakeholders feel that security measures are keeping malicious elements out and maintaining a safe space or confining students in a restrictive space? Are security measures perceived as reasonable and appropriate or hyper-vigilant and intrusive? Most importantly, do the security measures foster or hinder the development of an effective educational environment?

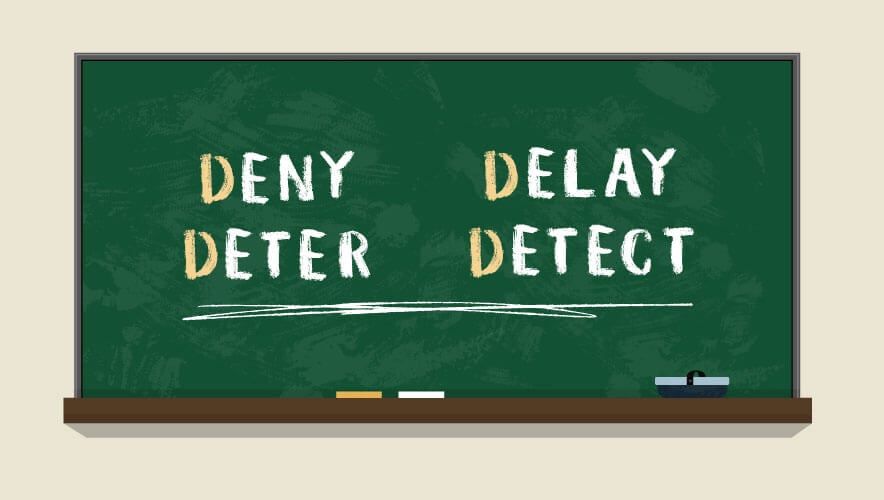

The use of highly visible and intrusive physical security measures in schools can often be seen as deterrence measures. Deterrence is a nebulous and difficult concept to quantify, particularly in the school environment. Deterrence assumes a rational actor, capable of accurate assessment of the environment they intend to attack. Most school shooters are not rational actors.

Additionally, the use of such measures can have an unintended effect. Staff and students can interpret highly visible and intrusive school security measures as an indication that the risk to the school is far greater than it really is. This perception will cause increased anxiety for both staff and students, negatively affecting the educational environment and the ability to both teach and learn. This need not be the case.

If climate is the perception of a school’s security measures, then culture is the acceptance and effective use of or rejection and ineffective use of a school’s security measures.

Following every high-profile incident of school violence, there is intense pressure for schools to do something. In response, schools can hastily implement measures that do not address their risk profile and have no long-term sustainability, but they make people feel good in the aftermath of these horrific incidents. This is the knee-jerk reaction of overcorrection.

Security measures that do not involve school staff in their development and are highly intrusive of the educational process run the risk of fundamentally altering the perceived nature of school. In these scenarios, it will be difficult if not impossible for schools to implement and sustain the security measures—there just isn’t enough buy-in for the perceived level of disruption.

Equally concerning is under-correction and the failure to reasonably address the lessons that unaffected schools could learn from someone else’s misfortune. The normalcy bias promotes returning to business as usual after an incident. There is immense institutional inertia in schools, and change does not come easily. Security professionals need to help schools guard against this.

When working with schools and engaging with their staff, security professionals need to understand the tyranny of the immediate concerns that overwhelm educators every school day. Concern about acts of school violence is an issue for educators, but of much more immediate concern is the lack of two substitutes with school starting in two minutes, the angry parent waiting in their office, the late buses, the restroom out of order, and a dozen other issues that require an immediate resolution. A building administrator told me, “The stuff that you talk about is what keeps me awake at night. It’s not what consumes my time and energy every day.” Keep this in mind when trying to help educators make security a priority.

Effective school security implementation requires both a security-friendly school culture and an education-friendly security posture. Effective school security accepts the competing operational realities that exist in a healthy school environment. The needs and exposure will be unique for each school, so a comprehensive risk assessment is an indispensable initial step. The second step is understanding the educational context for the measures we recommend. A balanced, effective, implementable, and sustainable school security plan will require intentional collaboration, thoughtful consideration, behavioral change, enculturation, and time.

Security professionals understand effective security practices. Educators understand the context of their educational environment. Security has a primary focus on the creation of a secure environment. Educators have the primary mission of education. Security lives in the world of “when, not if.” Educators live daily with the tyranny of the immediate. It will be incumbent on security professionals to understand both effective security and educational context. More secure schools will require common understanding, collaboration, and the good faith efforts of both groups to create the castle for learning that all schools should be.

As an educator, I lament the loss of the educational environment from the pre-Columbine beginning of my education career. As a school security professional, I regret the necessity for my expertise in today’s educational environment, but I actively embrace the challenge.

Guy Bliesner is a founding member of the Idaho Office of School Safety and Security, and he serves as a school safety and security analyst assigned to schools in southeast Idaho.