Who’s Liable for an Active Shooter Incident? Expectations Are Changing

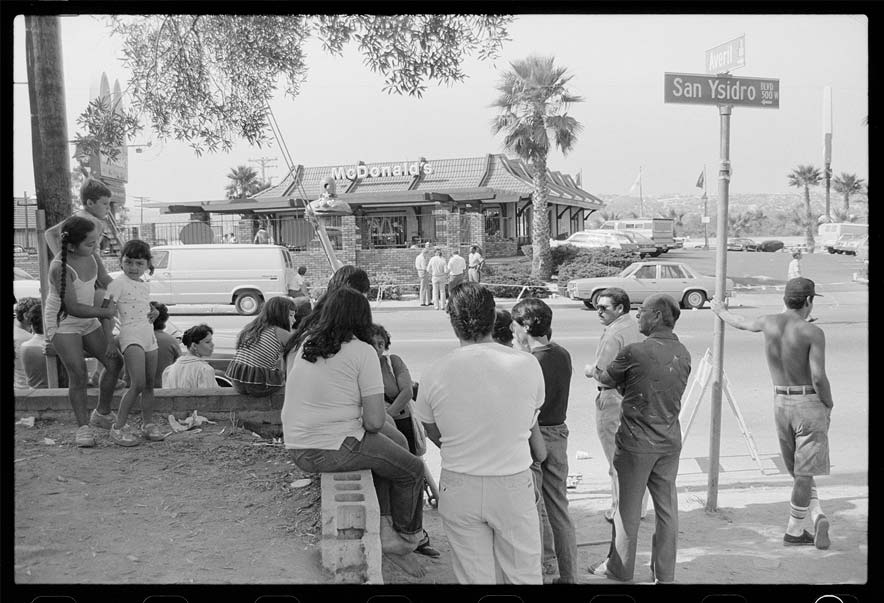

A gunman opened fire on a McDonald’s in San Ysidro, California, in 1984, killing 21 people and injuring 19 others. The incident was one of the first modern mass shootings to be followed by a negligent security lawsuit. Victims’ families and survivors sued McDonald’s, arguing that the company was negligent because it did not hire private security for the restaurant despite its location in a high crime area. The court disagreed.

The “deranged and motiveless attack…is so unlikely to occur within the setting of modern life that a reasonably prudent business enterprise would not consider its occurrence in attempting to satisfy its general obligation to protect business invitees from reasonably foreseeable criminal conduct,” the Court of Appeals of California wrote in its decision (Lopez v. McDonald’s Corp), dismissing the case.

Today, however, mass shootings in the United States are not rare events. As of Security Technology’s press time, there had been 371 mass shootings—incidents where four or more people, not including the shooter, were killed or injured—in the first seven months of 2022 alone, up from 272 total in 2014, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

The increasing number of these incidents is having an impact on how courts assess liability when a shooting occurs because mass shootings are no longer as rare as a “meteorite falling” from the sky, says Michael Haggard, managing partner at the Haggard Law Firm, who is representing the families of two victims and a teacher injured in the 2018 Parkland high school shooting.

“Liability for businesses in mass shootings is something they should be very, very concerned about,” he adds. “Every business, every school better have a security plan to deal with mass shootings. And they better enact it because if they don’t, they are going to be found liable.”

A Shifting Landscape

How courts assess liability changes over time in response to precedent, new laws, and societal evolution. After attending a conference where the issue of liability in response to mass shootings was raised, Michael Steinlage, partner at Larson King, decided to dive into the topic.

His research resulted in “Liability for Mass Shootings: Are We at a Turning Point?” published by the American Bar Association in February 2020, which identified that before the 1966 University of Texas shooting, there were only 25 public mass shootings where four or more people were killed.

“Since then, the number of such shootings has risen dramatically, and many of the deadliest shootings have occurred within the past few years,” Steinlage wrote. “Of the 220 incidents that occurred from 2000 to 2016, nearly half (107) took place in an education, retail, or government/military setting.”

Additional insights from Haggard’s firm based on research from Harvard University and Northeastern University found that mass shootings are increasing. Since 2011, for instance, mass shootings are occurring every 64 days in the United States—up from an average of every 200 days prior to 2011. And six in 10 Americans are now concerned that a mass shooting could happen in their neighborhood.

Steinlage’s analysis looked at third-party liability for mass shootings—where an individual sues a business or another entity for causing alleged harm. He particularly focused on how, in most instances, business owners are not considered liable to individuals who are injured by the criminal acts of another person unless that act was foreseeable—such as the business receiving a specific threat in advance of an act of violence. Courts have also upheld that “foreseeability of mass shootings cannot be established through local crime rates or general evidence of a criminally active environment,” Steinlage wrote.

Since February 2020, Steinlage tells Security Technology that more companies are being sued for having some role in failing to stop or failing to identify a shooter before an incident. It has also become more difficult for those lawsuits to be dismissed in the early stages of the suit, given how the law has developed about the role companies should take in preventing these incidents and around the subject of immunity.

“It comes down to the scope of their duty, which is generally measured by the concept of foreseeability and is something a risk? Is it something foreseeable that they knew something about? And should therefore have a duty to do something to prevent it?” Steinlage says. “Traditionally, the courts said nobody could foresee or be responsible for random acts of violence from a third party. Over the years, courts have started to chip away at that and held that in some cases, these types of events might be foreseeable and there is some duty to take precautions against them.”

One recent case that struck away at this concept was Wagner v. Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. In 2015, a gunman had traveled with weapons to the Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs to wage “war” because the clinic provided abortion services, the U.S. Department of Justice said. The attack killed three people, including a police officer, and wounded eight others.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit argued that if the Planned Parenthood clinic had taken certain security measures, the gunman might not have been able to gain access to the building because he encountered more resistance—and could have been stopped before carrying out further violence, Steinlage adds.

The Planned Parenthood case was initially dismissed due to lack of foreseeability. On appeal, though, a higher court reversed the dismissal, and the Colorado Supreme Court upheld that decision to let the case proceed to a jury trial. In October 2021, a jury ultimately decided that Planned Parenthood was not liable.

To avoid this in the future, Colorado Governor Jared Polis in April 2022 signed into law legislation that clarifies landowner liability based on the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling. The Colorado law now says that foreseeability for third-party criminal conduct cannot be based upon whether the goods or services provided by a landowner are controversial.

Another major series of cases closely watched to assess how liability is shifting were civil lawsuits filed by the families of victims of the Virginia Tech University shooting. The attack was carried out by a student and resulted in 32 people being killed and 17 being injured. Initially, a jury ruled that the university was liable for the deaths of Julie Pryde and Erin Peterson.

Later, however, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned that decision because the university did not have a duty to warn students about the potential for criminal acts being carried out by a third party—in this instance, a fellow student.

Settlements of Note

Some recent mass shootings have led to major settlements on behalf of property owners and their insurance providers with survivors and victims’ families, such as the $800 million settlement from MGM to victims of a shooting targeting a Las Vegas music festival carried out by a gunman staying at an MGM property. But that does not mean that a jury would rule in victims’ favor in every case that went to trial, Steinlage adds.

For instance, juries might still be inclined to say the shooter is the true cause of damage and that a business could not always be expected to know it was a target.

“There is an argument that it’s just not fair to expect that a business should protect itself against a random person intent on violence,” Steinlage says. “Given how many guns there are in the United States, it’s an impossible task. I haven’t seen a court use that as grounds for granting or denying summary judgement on a legal basis, but you could see a jury doing that.”

Other tactics on changing the way liability is assessed are also in play.

Since 2005, firearm manufacturers have been shielded from liability from crimes carried out using their products under the U.S. Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act. But after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in December 2012, families of nine victims sued Remington—the manufacturer of the firearm used in the shooting—with claims that its product should never have been sold to the public. The case reached the Connecticut Supreme Court, which ruled that under state law the families could sue Remington for how it marketed its firearms.

Remington appealed the court’s decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to take the case. The company then agreed to a $73 million settlement with the families in February 2022, according to the Associated Press. The settlement amount is covered by insurance companies that represented Remington, which also filed for bankruptcy.

The settlement marked some recognition of the potential for liability, Steinlage says, adding that the same could be said for the MGM settlement. MGM was “fortunate” that it had a “significant amount of coverage that was able to pay out on the claim,” he explains. “But they wouldn’t have paid out if they didn’t think there was a real risk of liability.”

Since the announcement of the Remington settlement in February, the U.S. state of California has passed legislation—effective in 2023—that will allow state, local government, and Californians to sue gun manufacturers for the harm their products cause.

While the California law does not directly address school and campus security, Haggard says it represents a “huge advancement” for the ability to hold gun manufactures liable for mass shootings and mass shooting negligence.

“Now these cases are going to trial, so it’s an issue for every business,” he adds.

The Insurance Impact

With the changes in court proceedings and U.S. state laws, insurance providers may be requiring organizations to take additional steps to mitigate the threat of a mass shooting or might provide resources to implement those steps.

Marsh McLennan—a global insurance provider—underwrites active assailant coverage, also known as active shooter coverage or deadly weapons coverage, that also typically covers the costs of advisory services to help businesses assess their risk, conduct training for employees, and develop active shooter response plans.

Additionally, the policies typically cover property damage, business interruption, legal liability, non-physical damage, loss of attraction, reimbursement for consultant services and post-incident care, and additional security.

“Some of the earlier policies provided for enhanced security on the anniversary of an event on the assumption that in some cases, there’s a greater likelihood of something occurring,” Steinlage says.

But with the number of shootings on the rise in the United States, Steinlage says that policies may become more expensive. Analysis from the Insurance Journal found that costs for insurance protection from mass shootings rose more than 10 percent in the United States in 2022, with clients looking to purchase policies to cover $5 to $10 million compared to $1 to $3 million in 2018.

Steinlage also added that these policies may include more exclusions for the types of incidents that can be covered.

“There are already assault and battery, and firearms exclusions in bars and restaurants,” Steinlage says. “More and more of those types of exclusions are showing up in a broader range of policies.”

Policy and Technology

U.S. lawmakers are also changing their approach to firearms. In June 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden signed into law legislation that expands background checks for potential firearms purchasers under age 21, invests millions of dollars into intervention programs for mental health, tightens restrictions on trafficking guns and making straw purchases, and creates additional resources for local governments to implement red flag laws—which allow authorities to temporarily confiscate firearms from individuals determined by a judge to be too dangers to possess them.

The new law, however, does not make major changes to the number of firearms already in circulation in the United States, which means that security teams will continue to play a large role in preventing and responding to shootings.

With the school shootings at Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Uvalde, Haggard says that every school district should be looking at access control measures to protect their campuses.

“When you think of Sandy Hook, Uvalde, and Parkland, all three of those shooters came from off-campus. None of them were students who snuck guns in,” Haggard explains, adding that schools need to take a look at how people are gaining access to their campus, and the type of security that needs to be implemented to harden their access control.

Additionally, security measures should be in place to control access and screen visitors for events on campus—such as metal detection wands or bag searches at football games or musical performances.

Haggard also suggests campuses look to adopt technology that can automatically detect when a gun has been fired to initiate an immediate lock down and response.

“There’s technology out there that the minute there’s a shot, they can identify what type of weapon it is, notify the police, and more importantly, shut down the school,” Haggard says. “An alarm goes off, every teacher pulls their doors—reinforced doors—and every classroom is shut down. There’s no way anybody’s getting in there.”

One security measure that has been enacted in some areas—allowing teachers to carry firearms on campus—is not one Haggard recommends, however, saying it is not a solution to address an active shooter armed with an AK-47 or AR-15.

“If the federal government does not want to take away these weapons of military advancement, then target harden the schools,” Haggard says. “Access control, security out front, and other technology inside the school. That’s not chump change, but if we’re not going to get rid of the guns, we better do something.”

Megan Gates is editor-in-chief of Security Technology. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @mgngates.