Cause for Caution, But Not Alarm, as Monkeypox Spreads

Monkeypox would likely be a worldwide news obsession if the world was not two-plus years deep into a deadly worldwide pandemic. Should you be paying more attention to the emergence of this disease than you are? Here’s the latest information.

Monkeypox cases have been confirmed in 18 countries outside of the equatorial African countries where the disease has been a small, persistent caseload for decades.

On Monday, the United Kingdom Health Security Agency reported 36 new cases in England, bringing the caseload to 56—the largest outbreak outside of Africa. Spain and Portugal have also reported more than two dozen cases in each country, and several other European countries have confirmed cases. Israel was the first to confirm a case in the Middle East on 21 May, while the United States (three confirmed cases), Canada (two confirmed cases), and Argentina (one confirmed case) have confirmed presence of the disease on the American continents. In the Asia Pacific region, only Australia has a confirmed case, a traveler who recently returned from a trip to Britain.

Current evidence suggests that those who are most at risk of being infected with #monkeypox are those who have had close physical contact with someone with monkeypox, while they are symptomatic. This includes health care workers https://t.co/8ewHPaN0VN pic.twitter.com/Dn6EI2pYhe

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) May 21, 2022

By far the largest outbreak this year is in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which has reported 1,238 cases and 57 fatalities according to the World Health Organization. Nigeria and Cameroon have also reported multiple cases (46 and 25, respectively).

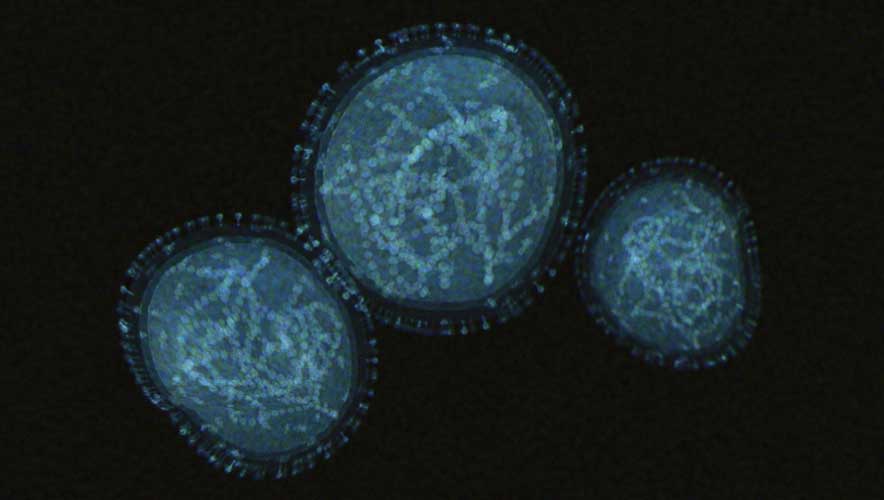

The basics: Monkeypox is a communicable disease, but it is not similar to the novel coronavirus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a New York Times explainer article, the disease was first discovered in primates in 1958, and first diagnosed in a human in 1970 in the DRC. Human cases of monkeypox generally results from close contact with an infected animal—typically a rodent of some kind, despite the name of the disease.

Since 1970 there have been small outbreaks of human-to-human transmission, mostly limited to a few hundred cases in Africa, which have occasionally spread to other countries due to travel. The current outbreak is the largest number of confirmed cases outside of Africa. While public health agencies are studying the situation, they stress there is no reason for alarm.

“As surveillance expands, we do expect that more cases will be seen. But we need to put this into context because it’s not COVID,” Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, the World Health Organization’s technical lead on COVID-19, said in a live online Q&A on Monday, the Times reported. “Transmission is really happening from close physical contact, skin-to-skin contact. So it’s quite different from COVID in that sense.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that “human-to-human transmission can result from close contact with respiratory secretions, skin lesions of an infected person, or recently contaminated objects. Transmission via droplet respiratory particles usually requires prolonged face-to-face contact, which puts health workers, household members, and other close contacts of active cases at greater risk.”

While the disease has had a resurgence in recent years, the WHO surmises this is likely the result of declining immunity derived from protections provided by smallpox vaccinations, which have been discontinued since WHO declared the virus eradicated in 1979. Reuters reported that WHO said there is no evidence that the disease itself has mutated to become more infectious.

As health agencies monitor the monkeypox outbreak, one of the steps is assessing the current stockpile of smallpox vaccines. Many countries keep doses of smallpox vaccine as a safety measure driven by fears of the potential of bioterrorism or biological warfare. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on 23 May that the U.S. has more than 100 million doses of the original smallpox vaccine, which would protect against monkeypox. A newer vaccine for both smallpox and monkeypox has also been approved.

The investigation into the European outbreak is centered on sexual activity at rave parties held in Spain and Portugal. Monkeypox has not been known to be prevalent in bodily fluids, so the transmission during sexual activity may be the result of skin-to-skin contact.

The Washington Post reported that most of the known European transmissions have been among men who have sex with men; however, experts stress that anyone can become infected through close contact with an infected person, including their clothing or bedsheets.

WHO reports that the “case fatality ratio has been around 3 to 6 percent,” though it should be noted that most cases through the years have occurred in areas without widespread availability of the most advanced healthcare.

It typically takes one to two weeks from before symptoms from an infection occur. The symptoms come in two waves, according to the WHO. The first period lasts up to five days and is “characterized by fever, intense headache, lymphadenopathy (swelling of the lymph nodes), back pain, myalgia (muscle aches) and intense asthenia (lack of energy).”

After fever onset, the disease manifests grotesquely, earning the pox moniker. A rash develops, typically on the face, palms of hands, and soles of feet. It can also affect the cornea and genital areas. From the rash, large pustule lesions can appear, which eventually crust up and fall off. “The number of lesions varies from a few to several thousand,” the WHO says. “In severe cases, lesions can coalesce until large sections of skin slough off.”