Editor's Note: In Sync

One night in 1935, naturalist Hugh Smith saw a bright flash of lightning along a river in Thailand. Then, lightning struck again. "In a reality-bending moment, all of the trees along the riverbank suddenly glowed in unison. Every tree on one side of the river for a thousand feet was flashing and going dark at the same time," writes Shawn Achor in his new book Big Potential.

Smith soon realized that the glow came not from lightning but from thousands of fireflies flashing in unison. Returning to the United States, Smith wrote about his findings only to be ridiculed from all sides. "Why would male fireflies glow in unison, which would only decrease their chances of distinguishing themselves to potential mates?" recounts Achor.

Scientists would later discover that Smith had uncovered a real phenomenon, and that the practice of synchronized flashing created a reproductive advantage for the fireflies. The success rate of male fireflies increased by 79 percent when fireflies flashed in unison rather than as individuals.

Focus then shifted to how the fireflies achieved this level of synchronization. "A few believed that there must be a maestro, a firefly that cues all the rest," according to Steven Strogatz in his book Sync. But the truth was far more fascinating. Fireflies do not have to see the entire group to coordinate the flashes, they only need to be in rhythm with their immediate neighbors.

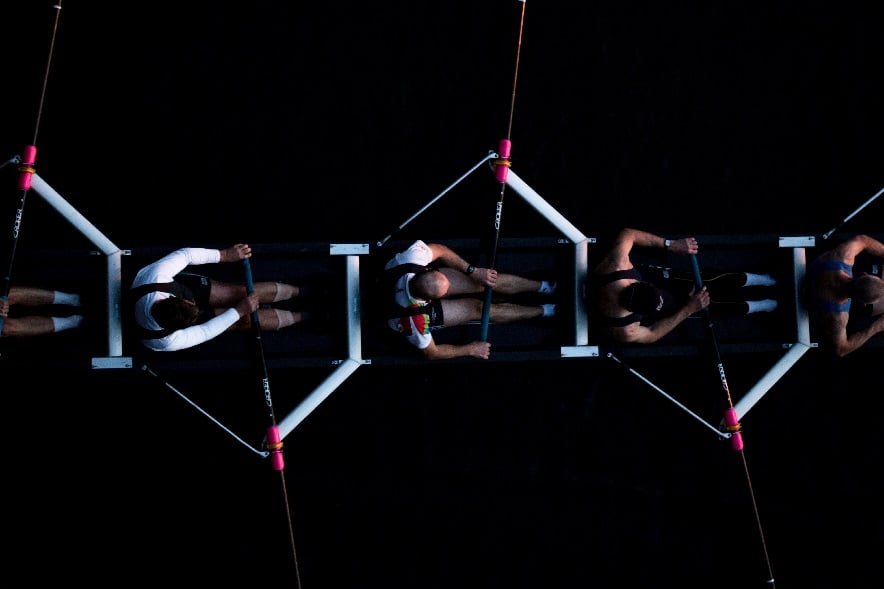

"In a congregation of flashing fireflies, every one is continually sending and receiving signals, shifting the rhythms of others and being shifted by them in turn. Out of the hubbub, sync somehow emerges spontaneously," writes Strogatz.

According to Achor, this firefly analogy perfectly illustrates the latest research into organizational success and personal happiness. Traditionally, Western culture has stressed the achievements of the individual, he notes. Organizational success, conventional wisdom says, is predicated on hiring the most successful individuals and letting them loose.

However, new research indicates that high achievement has little to do with the intelligence, creativity, or ambition of the individual. It is directly related to how well that individual can connect to other people. "It isn't just how highly rated your college or workplace is, but how well you fit in there. It isn't just how many points you score, but how well you complement the skills of the team," writes Achor.

Building and maintaining a successful team is critical to this month's managing article, "Performance Conversations: Checking In and Coaching Up," by Senior Editor Mark Tarallo. Typically focused solely on the success and struggle of an individual employee at one point in the year, reviews are pivoting to ongoing assessments of team members in their environment. Managers should attempt to meet employees where they are, as part of a team, instead stressing individual goals separate from the group.

"We now know that achieving our highest potential is not about survival of the fittest," writes Achor. "It is survival of the best fit."