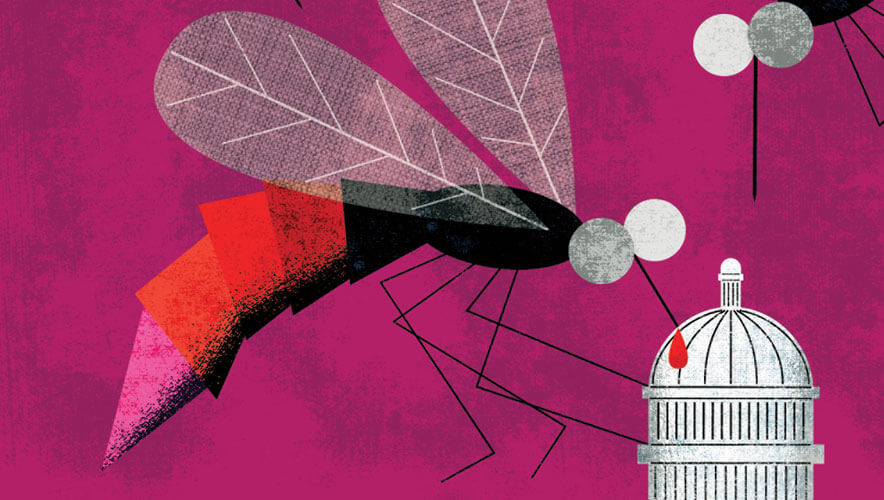

Urgent Calls for Bio Reform

Since the Zika virus started making headlines in January, the global health community has scrambled to address its spread in Latin America. The virus, which is primarily transmitted by mosquito bites, causes fever and rash in its victims, but it can also lead to birth defects in babies whose mothers contract the virus while pregnant.

Much like past global epidemics, such as smallpox, swine flu, and Ebola, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is addressing Americans’ fears: Will it spread to the United States? Will the CDC be able to control it? How will we know when it becomes an imminent threat in our communities, and how should we respond?

Although the CDC may be able to gain an upper hand on global epidemics, such as the Zika virus, the same cannot be said for more sinister biological events, such as an anthrax attack. The United States’ biosurveillance and biodefense activities are poorly coordinated, inefficient, and fragmented, according to multiple reports.

“Despite significant progress on several fronts, the nation is dangerously vulnerable to a biological event,” according to A National Blueprint for Biodefense. “The root cause of this continuing vulnerability is the lack of strong centralized leadership at the highest level of government.”

A number of federal agencies have had a role in addressing the threat of biological attacks since the 2001 anthrax attacks that killed five people and sickened more than 20. Detection technology, the study of biological weapons, and strengthened public safety protocols are all essential to protecting the nation from a biological event. But biosafety and biosurveillance programs in the United States have been plagued by setbacks and negative scrutiny over the past decade.

In 2014, multiple CDC laboratories studying anthrax, smallpox, and other dangerous pathogens experienced egregious breaches when live samples of the diseases were sent to laboratories with insufficient safety protocols, potentially exposing dozens of workers to the samples.

The BioWatch program, an early warning network of sensors that aims to detect biological attacks before widespread public infection can occur, has seen multiple setbacks, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) cancelled its efforts to improve the technology in 2014.

Similarly, the National Biosur-veillance Integration Center (NBIC) has come under the scrutiny of the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which found that the program is limited in its ability to enhance the national biosurveillance capability.

These incidents and more are addressed in the candidly written A National Blueprint for Biodefense, conducted by the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, which “examined the national state of defense against biological attacks and emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, of the order that could cause catastrophic loss of life, societal disruption, and loss of confidence in our government.”

The panel is made up of bipartisan lawmakers and biosurveillance experts, including former Senator Joe Lieberman and former Governor Tom Ridge. The report points to both naturally occurring threats, like the Zika virus, and biological weapons, which terrorist groups such as ISIS encourage followers to use, as grave threats to the country.

Information-sharing barriers and outdated detection technology contributed to the panel’s concerns, but the lack of centralized leadership, a strategic plan, or a dedicated budget comprise the greatest weaknesses in the nation’s biodefense, the report notes.

The document puts forth 33 recommendations on how to reform, fund, and organize the biodefense enterprise, with emphasis on empowering the U.S. vice president to lead the effort, prioritizing medical countermeasure development, and improving public-private partnerships to optimize industry participation. The leadership role should fall to the vice president, the report recommends, because he or she can take on the budget and bureaucratic hurdles that many federal agencies encounter.

Chris Currie, the director of emergency management and national preparedness issues at GAO, agrees that change in the biosurveillance enterprise is needed. Currie recently authored two GAO reports that focus on some of the programs A National Blueprint for Biodefense discusses. He tells Security Management that there are myriad federal agencies have some stake in biosurveillance, but there are inherent organizational, procedural, and information-sharing problems.

This is made evident in the BioWatch program, which has been receiving criticism since its launch in 2003. Since its inception, congressional studies, media investigations, and GAO reports have been conducted on almost every aspect of the pricey program—BioWatch has cost taxpayers more than $1 billion to date—from research and development practices to its effectiveness.

A National Blueprint for Biodefense puts it bluntly: “The entire BioWatch system is dying for lack of innovation.”

The currently deployed BioWatch system—Generation-2—has been around since 2005 and is supposed to detect the presence of airborne biothreat agents within 12 to 36 hours, although the National Academies has raised questions about Gen-2’s capabilities. Indeed, Currie points out that the BioWatch program was deployed in response to the anthrax attacks, and previous GAO reports have found that, in an effort to quickly deploy the program, DHS did not follow proper testing and acquisition procedures.

A few years ago, DHS turned its attention to new technology for BioWatch, known as Generation-3, that would essentially be a “lab-in-a-box.” Instead of having to manually remove sensors and test them for dangerous airborne particles, Gen-3 would autonomously collect, analyze, and report the status of samples.

The new technology would reduce detection time to less than six hours, compared to the current 12 to 36 hours. However, the acquisition of Gen-3 technology was abandoned by DHS in April 2014 after testing and financial difficulties.

“So basically, this new report is saying, ‘hey—you cancelled Gen-3 two years ago, it’s not clear what the next step in the program is, and you still have this existing program in cities around the country. What are we going to do with that, and how well does that work?’” Currie explains.

The 101-page report, titled DHS Should Not Pursue BioWatch Upgrades or Enhancements Until System Capabilities Are Established, revisits concerns about Gen-2 that have been brought up in previous reports, and it questions what steps DHS should take next in developing autonomous technology similar to Gen-3.

There are a number of issues with the current BioWatch technology, from the aforementioned lack of technical capability assessments to the fact that some of the Gen-2 equipment, which has been in use for more than a decade, is reaching the end of its life cycle.

Currie says that after DHS decided not to move forward with Gen-3, the responsibility of the future of the program shifted to DHS’s Science and Technology directorate, and it became unclear how the program would progress.

“Not a lot of attention was being paid to Gen-2 because the system was going to be replaced by Gen-3,” Currie says. “It’s been out there for a decade, DHS was moving towards an autonomous system, they were spending all our money and research on that. Gen-3 would drastically improve the speed and detection ability, so they pursued that. There wasn’t a lot of emphasis—and maybe rightly so—on going back and proving whether the current system did what it needed to, because it was going to be replaced.”

Ultimately, this most recent GAO report found that the lack of systematic testing means that “considerable uncertainty remains as to the types and sizes of attack that the Gen-2 system could reliably detect.”

The report also identified an alternative autonomous technology called polymerase chain reaction. But challenges remain in pursuing such a system. And as some Gen-2 equipment comes to the end of its life cycle, DHS must assess how to invest in the future of BioWatch.

A National Blueprint for Biodefense goes a step further and calls for the replacement of BioWatch Gen-2 detectors with a “21st Century-worthy environmental detection system” developed by DHS and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Another GAO report Currie authored, Challenges and Options for the National Biosurveillance Integration Center, assesses the NBIC, which was established in 2007 within the DHS and is tasked with “integrating and analyzing information from human health, animal, plant, food, and environmental monitoring systems across the federal government and supporting the interagency biosurveillance community.”

NBIC is responsible for coordinating the missions and resources of 14 federal departments and agencies that comprise the National Biosurveillance Integration System (NBIS) and for sending out daily biosurveillance monitoring lists and special event reports to those departments. Overall, the program was supposed to be the information-sharing hub for all agencies that support biosurveillance.

However, NBIS agencies told GAO researchers that NBIC’s products do not provide them with meaningful information—oftentimes, the agencies are already aware of the information the NBIC sends out. This is because the NBIC has limited access to actionable data, despite the program’s charge to be a premier resource for biosurveillance information.

“Apart from searches of global news reports and other publicly available reports generated by NBIS partners, NBIC has been unable to secure streams of raw data from multiple domains across the biosurveillance enterprise that would lend themselves to near-time quantitative analysis that could reveal unusual patterns and trends,” according to the GAO report.

Further, some agencies are reluctant to share their data with NBIC because they are unsure how it will be used—a classic federal information-sharing barrier, Currie says—and the program faces regulatory and legal hurdles in acquiring sensitive data.

“Sharing such information too broadly might have substantial implications on agricultural trade or public perception of safety,” the report notes. Overall, the NBIC’s mission is virtually impossible to achieve due to its lack of resources, Currie explains.

The GAO report recommends that NBIC refocus on gathering and analyzing “seemingly unrelated datasets,” instead of releasing daily reports with information that most of the agencies already have. Other options include strengthening NBIC’s coordinator or innovator roles, or completely repealing the NBIC statute and pushing funds to other biosurveillance programs.

A National Blueprint for Biodefense cites NBIC’s challenges as another reason why the White House should be more involved in biosurveillance.

“The lack of required interagency sharing of surveillance data means that NBIS can only function properly if the White House forces it to work,” the report says. “Without a strong and enforced executive order requiring agencies to cooperate on biosurveillance and detection, share data, and staff such a venture comprehensively, NBIS will continue to fail to fulfill its mandate.”