The Tase Craze

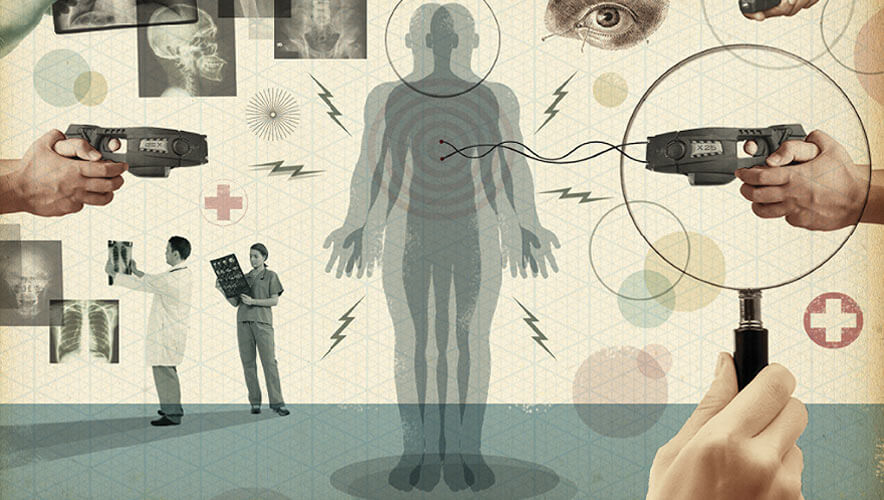

Taser use is on the rise worldwide, and with it comes more scrutiny and study, on both its health effects and its potential to reduce violence.

When it comes to policing tools, body cameras have been the focal point of public discussion and debate over the last few years. But there’s another device that is also increasingly being used worldwide and is receiving considerable scrutiny: Tasers.

Recent studies, including a new report from the British Medical Journal (BMJ) as well as other research and statistics, point toward two conclusions that may appear contradictory, but are actually not mutually exclusive. The BMJ report finds evidence that Tasers pose health risks of varying sorts.

Other studies, however, seem to support the argument that Tasers are an effective tool that may ultimately reduce the number of violent assaults, and sometimes even save lives.

Tasers, the electroshock weapons manufactured and sold by the Scottsdale, Arizona-based Taser International, Inc., have their roots in fantasy. NASA researcher Jack Cover, developer of the first Taser, was a childhood devotee of Tom Swift, the protagonist of a popular series of adventure novels. Cover has said that he was long fascinated by the weapon Swift used in the novels—a gun that could stun people with “blue balls of electricity.” And so, when Cover completed his prototype in 1974, he named it in honor of Swift—Taser is an acronym for Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle. However, Cover’s original model still used gunpowder and so was officially classified as a firearm by the government.

In the 1990s, Taser International Inc., working with Cover, developed a gunpowder-free version. From this work came the contemporary Taser, in which compressed gas is used to fire two dart-like barbed electrical probes. Police use these, most commonly, to subdue fleeing or potentially dangerous people, instead of subjecting them to lethal weapons. Tasers may also serve as a less violent alternative to submission methods, like chokeholds and baton strikes.

In recent years, the use of Tasers (which are sold to private citizens, as well as police) in the United States has grown to the extent where they are now part of popular culture. In 2007, a video of University of Florida student Andrew Meyer yelling “Don’t tase me, bro!” to a campus police officer became a national viral sensation.

YouTube features countless videos of Americans shooting themselves and their friends, for intended comic effect. The back-formed verb “tase,” defined as “to shoot a Taser,” is now included in American dictionaries.

Taser use has also grown around the globe. They are now used in 107 countries by more than 16,000 police forces. Worldwide, police used Tasers to shock people roughly 650,000 times during arrests and stops in 2013, according to the BMJ study.

In many individual countries, use is also on the rise. In the United Kingdom, for example, police officers not trained in firearms were first allowed to carry Tasers in 2009; Taser use then tripled between 2009 and 2013, according to the BMJ study.

But this widespread use is drawing continued scrutiny regarding the potential health effects of Tasers. The electrical probes shot out of a Taser deliver a pulsing 50,000-volt shock, which causes skeletal muscle contractions and pain. Some models also have a drive-stun mode, in which two electrodes at the front of the weapon are held against the body, causing pain but not muscle contractions.

According to the BMJ report, health risks from Tasers include eye injuries; seizures, especially for people with epilepsy; skin burns; muscle, joint, and tendon injuries; and pneumothorax, or a collapsed lung. The most dangerous risk, according to the report, is head injury from uncontrolled falls, which has led to deaths in some cases.

Moreover, an investigation by The Washington Post, which examined police, court, and autopsy records, found that at least 48 people died in the United States from January through November 2015 (about one death a week) during incidents in which police used Tasers.

However, the link between the use of Tasers and the deaths was unclear in the investigation. At least one of the deaths occurred when an incapacitated person fell and hit his head. Various causes of death have been cited in the 48 cases, including excited delirium, methamphetamine or PCP intoxication, hypertensive heart disease, coronary artery disease, and cocaine toxicity.

In the investigation, the newspaper was able to obtain either autopsy reports or cause-of-death information in 26 of the 48 cases. Of those 26, 12 autopsies mentioned the Taser, along with other factors, in describing the death, but did not directly attribute the Taser as the sole cause of death.

In addition, at least nine of the 48 cases involved individuals who were tased in drive-stun mode, where the electrodes are held against the body. Drive-stun is a more controversial method of using a Taser. Back in 2011—in a report titled Electronic Control Weapon Guidelines—the Police Executive Research Forum recommended that drive-stunning be discouraged, and only be “used in close quarters for the purpose of protecting the officer or creating a safe distance between the officer and subject. Absent these circumstances, using the electronic control weapon in drive-stun mode is of questionable value,” the report says.

However, another recent study, funded by the International Healthcare Security and Safety Foundation (IHSSF) and conducted by Duke University Medical Center, found that Tasers are an effective security tool in healthcare settings.

The study, released in October 2014, examined hospital safety and security practices, and evaluated how security practices, including the use of weapons by security personnel, can prevent and mitigate violence in hospitals.

The IHSSF study assessed incidents of violence in the hospital setting in a recent 12-month period, including the association between violence and weapons use among security personnel. According to study findings, handcuffs were the most common type of weapon available to be carried and used by hospital security staff (96 percent), followed by batons (56 percent), products such as pepper spray (52 percent), hand guns (52 percent), and Tasers (47 percent).

There was a 41 percent lower risk of physical assaults among hospitals with Taser-armed security personnel than hospitals that did not employ Tasers, the study found.

“This study shows a lower risk of physical assaults in hospitals in which Tasers (or similar devices) were available to security personnel, which suggests these devices may be useful tools for de-escalating and controlling potentially violent, or already violent, situations,” IHSS Foundation President Steve Nibbelink said in a statement.

Nonetheless, the group does not expect the study to be the final work on Taser use. “The debate continues about whether the availability and utilization of weapons by security personnel in the hospital setting is wise, especially the use of Tasers,” he added.

And as for Meyer, the college student who, despite his exhortation to the contrary, was in fact tased in the 2007 incident—he turned out okay. He later trademarked his phrase, and made some money selling his own line of Don’t Tase Me Bro T-shirts.