New Guidance Needed

With predictive policing and other strategic practices, technology is changing—if not transforming—law enforcement. But real-world budget constraints prevent all 18,000 U.S. law enforcement agencies from having access to any and all useful technology.

Thus, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), which serves as the national focal point on criminal justice technology, tasked the RAND Corporation with determining the current highest priority IT needs for U.S. law enforcement agencies. The report, High Priority Information Technology Needs for Law Enforcement, finds many needs. But a striking finding, according to the lead author of the report, is that one of the most pressing priorities is not for any one type of technology, but for more guidance, policies, and evaluation for the use of technology.

“What we thought we would find was the need for new technological widgets,” John Hollywood, senior operations researcher for the RAND Corporation, tells Security Management. “But what we really found, and what turned out to be the key theme, was the need for more knowledge about technology.”

The report focuses on three overarching findings, or three broad needs: to improve the enforcement community’s knowledge of technology and practices; to improve the sharing and use of relevant information; and to conduct research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E) of different facets of IT.

The report calls for RDT&E in seven key areas. For example, the report finds that research is needed on both the traditional technical development side of IT and the “nonmaterial” side, which includes policy and practices research. In the latter category is the need for more RDT&E aimed at improved use of social media.

“That played out in several ways,” Hollywood says. One was that law enforcement agencies could use social media to better communicate with the public, such as by sending out information bulletins over social media channels and broadcasting alerts about areas that should be avoided due to recent incidents. Another was better use of social media for “reverse feeds,” to solicit tips and intelligence from the community, Hollywood says.

As it happens, this need for improved social media use is consistent with a finding from another study, conducted by the ASIS International Crisis Management and Business Continuity Council, on the subject of how social media is being used in emergency management. The study, Social Media is Transforming Crisis Management, found that while 55 percent of police departments surveyed actively use social media in performance of their duties, there are three main barriers to better use: a lack of personnel or time to work on social media, a lack of policies and guidelines, and concerns about the trustworthiness of collected data. (See the September 2015 cover story for more details on the ASIS report’s findings in the private sector.)

In the RAND report, another one of the seven RDT&E findings is a need for improved health systems for enforcement officers, for both physical and mental health. Officers occasionally die in the line of duty for health reasons like heart attacks, which indicates a real need for physical health monitoring, the report finds. And there is also a clear need for improving the availability of technology related to mental health, such as telepsychiatric services, and other ways of responding to early warning signs, Hollywood says.

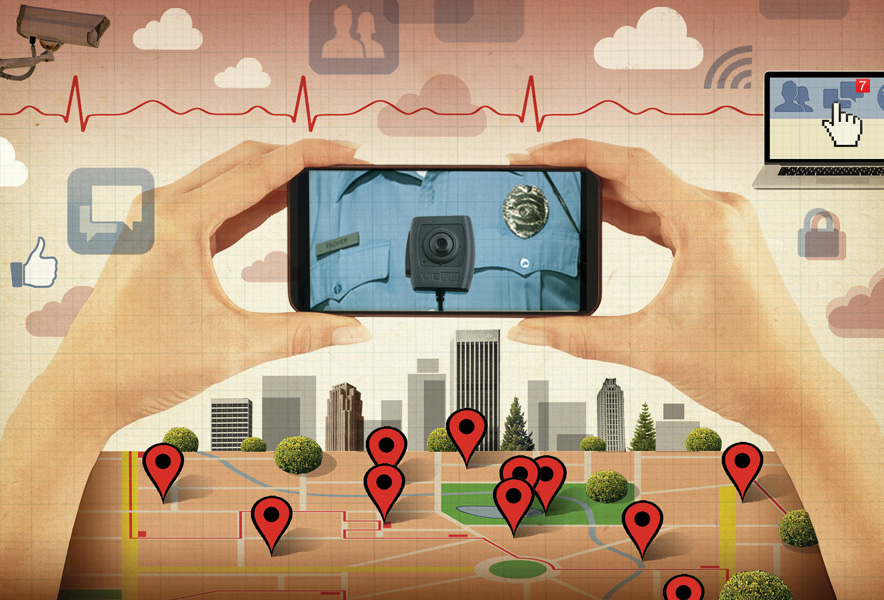

Another of the seven findings is a need for more RDT&E to improve deployable sensor systems, such as lightweight body-worn cameras. Body cameras are an area of technology that “just kind of really exploded” in the last few years in terms of demand and debate over use, Hollywood says. The report finds several needs in this area; first, there is a need for more comprehensive general use policies about when to record, when not to record, who should get access to footage and under what circumstances. On some of these issues, such as questions of access, there is significant variance in laws state by state.

Guidance is also needed on how to work with incidents that are covered by video from multiple perspectives, Hollywood says. “Officers on the scene have cameras. Bystanders are filming. And in some engagements, people who are involved in bad behavior are also filming,” Hollywood says. He mentioned an example he came across in his work, where a suspect charged with loitering and public intoxication started filming the interaction, then shifted the camera away and shouted, “Why are you beating my brother?”

Similarly, the report found a need for RDT&E for cybersecurity issues that come up with use of new IT tools—issues like data hacking and privacy concerns related to social media. Like body cameras, cybersecurity is an area where interest has risen tremendously, but police departments need clearer policies and more guidance. “These are law enforcement experts. They’re not experts in cybersecurity,” Hollywood says.

Besides the need for more guidance and policy, there is another crucial issue that affects the use of IT by law enforcement: moving forward, how will technology affect the relationship between law enforcement and the community it serves? That subject is covered in another recent report, Visions of Law Enforcement Technology in the Period 2024-2034: Report of the Law Enforcement Futuring Workshop.

As implied by its title, this second report envisions what the future of technology use will be like for law enforcement. Like the first report, the second report was sponsored by NIJ’s Office of Justice Programs, and was conducted by the RAND Corporation under the auspices of its Safety and Justice Program.

The report sketches out how criminals might use technology in the future, to give an idea of what law enforcement will be up against. “As emerging technologies develop further, one can envision, for example, cyberattacks on medical devices such as pacemakers or the use of the “Internet of Things” to identify targets or create situations that require police response,” the report says. “There is also the possibility of criminals embedding technology in public or private systems for later use.”

To combat threats such as these, enforcement agencies will be driven to increase their use of technological tools. For example, the report predicts that agencies will expand their surveillance capacities as the number and location of all types of cameras increases; that the use of cloud computing will increase in part to reduce physical infrastructure in agencies; that the use of advanced data collection and analytics will increase, to improve situational awareness for officers in the field; that the use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to monitor officer location will increase; and that there will be increased use of military-style equipment, such as high-performance wearable cameras that afford greater range of vision.

But along with these predictions, the report also raises a key question: will law enforcement agencies be able to retain public support for this ever-expanding use of technology? Or will there be a backlash and loss of support from a public that sees this expanded IT use as too intrusive, and possibly too militarized?

The report’s conclusion is that the path to a desirable future, where law enforcement is effective and its use of technology is supported by the community it serves, is built on three principles: information sharing, education and training, and partnerships.

Partnerships, such as with the private sector, the public, and nonprofit organizations, can help with the cost-effective adoption of new IT systems. Education should be aimed at officers on all levels, “both on the latest technologies and in their effective and least intrusive use,” according to the report. And information sharing must be two-way, so that it fosters an enduring relationship between the agency and the people it serves.

“It must provide rapid information dissemination and a vehicle to support clear understanding—both law enforcement’s understanding of community needs and desires, and public understanding of law enforcement needs and operational realities,” the report says.