‘Pen-Tested’ by a Hacker: What to Believe

When actors from the Babuk ransomware gang announced the start of their operations on underground forums in 2021, they advertised their services as special software to “show the security issues inside corporate networks.”

As the ransomware-as-a-service (RAAS) landscape has exploded during the past three years, more and more groups have taken a similar position to the Babuk gang, framing themselves as “penetration testers” and promising victims a comprehensive security report if they pay the ransom demand. Failing to pay the ransom, though, would result in public disclosure of the vulnerabilities—effectively leaving the company wide open to attack.

While these threat actors claim altruistic objectives in exposing security flaws, the end motive for these groups is to secure payment from the ransom demand. In reality, it is not altruistic, but a thinly veiled way of incentivizing the victim to pay up.

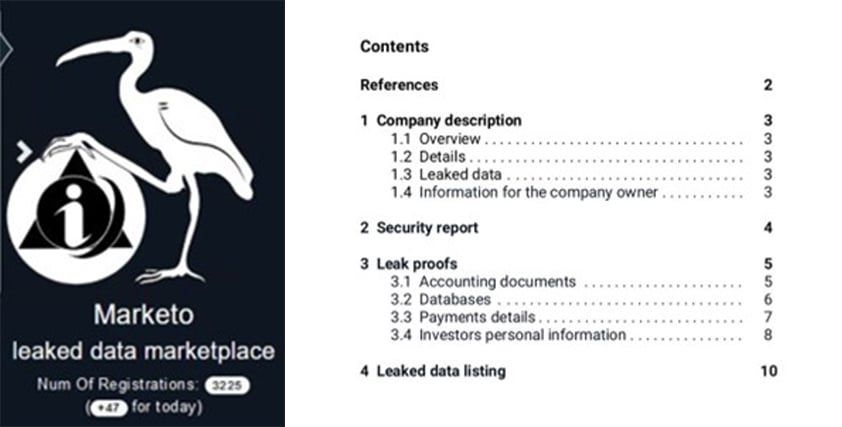

Through Kroll’s incident response and Dark Web monitoring investigations, we have observed a number of such security reports—both public and private. Reports vary from threat actors who respond with a one-line email such as “we guessed the password” to longer in-depth analysis breaking down the network by multiple criteria, such as in the case of the operators of the Marketo market (see Figure 1).

In other cases, threat actors have promised a security report but never delivered, leaving the company financially worse off and wondering whether their network vulnerabilities are about to be published online. Consequently, we recommend avoiding engaging with threat actors to obtain one of their vulnerability reports.

Instead, firms should engage with experts in this field of cybersecurity, either within their organization or through a third party. Two key things need to take place: first, response to the current threat actor situation, done in a way that is managed and mitigates potential damage. Second, we recommend a penetration test with a legitimate provider that can conduct a full and transparent assessment, within legal boundaries.

That said, it is interesting to understand what common vulnerabilities threat actors are focusing on. Key themes that we have identified across multiple reports include password hygiene, susceptibility to phishing emails, and legacy application vulnerabilities.

Password Hygiene

One of the most mentioned attack vectors from the sample security reports Kroll observes is the vulnerability of passwords, specifically passwords that are inherently weak or easily decrypted.

For example, one report referred to a domain administrator account being secured with a “password1234” complexity-level password. Worse still, threat actors noted that often these passwords were reused across multiple different accounts. In other instances, passwords that were saved in browsers made it easier for threat actors to laterally move across virtual and physical applications.

Susceptibility to Phishing Emails

As is well known, workforce susceptibility to phishing attacks has a significant impact on the number of threats able to gain a foothold in the network. Kroll has observed security reports, which pick up on this.

Some threat actors encourage conversations with employees on not opening emails with attachments from an unknown source until they are convinced that the file will not harm their PC. In other instances, it has been suggested that employees who open suspicious emails should be “punished with money,” perhaps suggesting that organizations fine end users. Actors also indicated that quality anti-spam protection, which checked email attachments for viruses, would go a long way to reduce the damage caused by a phishing email.

Legacy Application Vulnerabilities

Many reports note that the threat actor used “public vulnerabilities” to access networks, for example, the Log4j exploit or a virtual private network (VPN) vulnerability. There has also been reference to operating systems (OS) requiring updates in terms of their security criteria.

Other mentioned security flaws included the lack of multifactor authentication or the ability to bypass multifactor authentication via IMAP, legacy source code or applications that were still active or open to the Internet, and poor network segmentation. Interestingly, more than one report mentioned that networks with endpoint detection and response (EDR) or intrusion detection systems (IDS) were the hardest ones to intrude.

There are a number of mitigation strategies organizations can use to avoid being compromised by cybercriminals using these methods.

For example, maintaining and enforcing a password policy with rules for unique, complex passwords that include a combination of letters, numbers, and special characters. It is also wise to educate users on the dangers of password reuse. Enabling multifactor authentication (MFA) for login accounts will also serve as another protective barrier to keep threat actors out of your network.

When it comes to phishing attempts, it is important that organizations take a multi-layered approach to protecting their network. While the threat actor reports focus on user education for combatting phishing, we recommend combining that education with other security controls such as email spam filters to remove suspicious emails from the inbox and a managed detection and response (MDR) system to help identify and quarantine malicious activity before it spreads across the network.

Finally, organizations should take note that threat actors can and will compromise outdated software. They need a robust patch management program to identify and prioritize new vulnerabilities to update systems as appropriate.

With threat actors continuously finding new ways to compromise and extort businesses, it is imperative that organizations work twice as hard to protect themselves. Critical to this is regular penetration testing by a legitimate organization that can identify vulnerabilities and weaknesses that threat actors may attempt to exploit. Above all, organizations should remember that these are criminals who shouldn’t be trusted; just because they’ve found a way into your network, doesn’t mean you should trust their cybersecurity advice.

Laurie Iacono is associate managing director, Cyber Risk, Kroll. She assists clients with investigative and technical support in incident response and Dark Web monitoring. Prior to joining Kroll, Iacono managed the Brand and Consumer Protection program at the National Cyber-Forensics Training Alliance.

© Laurie Iacono, Kroll