Murders, Gun Violence Down Slightly in 2022

With new mass shootings every week and plenty of other violent crime stories in the news cycle, you would be forgiven if this fact catches you off guard: so far in in 2022, the number of murders in the United States has decreased slightly compared to the year prior, as has the number of overall deaths resulting from gun violence.

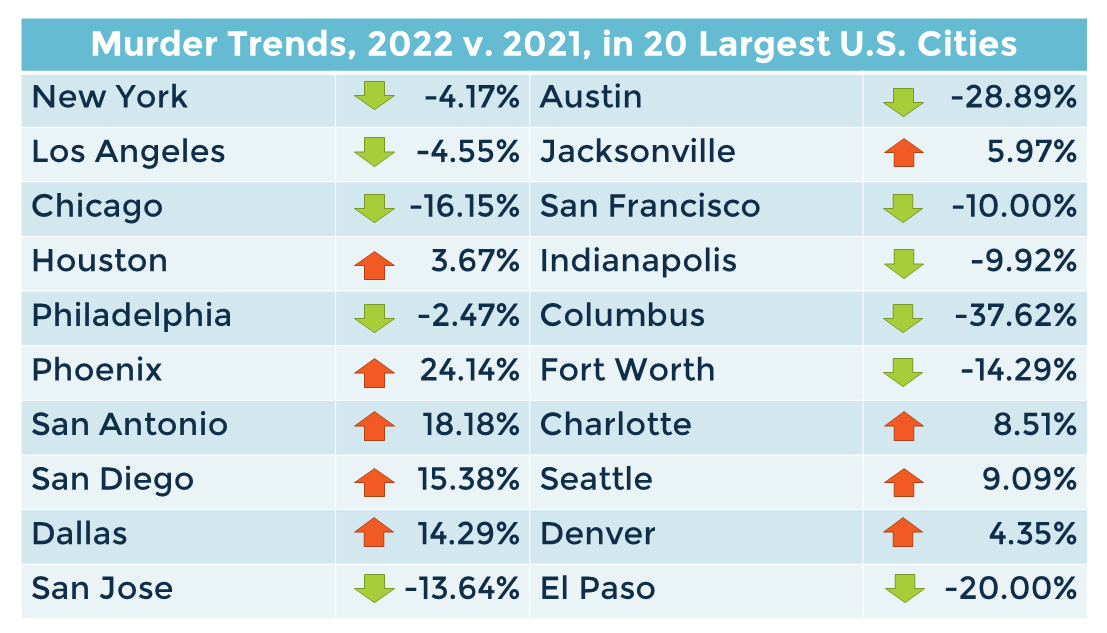

Data analytics company Datalytics has a real-time dashboard of murders. As of the morning of 9 August, it was reporting 4,850 murders this year, which is a 3.2 percent decline compared to the 5,011 reported up to this point in 2021. Of the five most populous U.S. cities, murders have decreased in four of them, with Chicago’s 16 percent decline leading the way.

However, the gains may be tenuous. Looking at the top 20 most populous cities, the number of murders has decreased in 11 of them and increased in nine of them. Also, Chicago alone accounts for 45 percent of the nationwide decline.

Data from the Gun Violence Archive reinforces the Datalytics slight downward trend thus far this year. In nearly every category that the Gun Violence Archive reports out weekly, there is a small decrease when comparing totals in 2022 through 8 August and totals in 2021 through 9 August.

See the two embedded Facebook posts below to compare 2022 to 2021.

From The New York Times article covering the trend:

“I would say I have a heavily guarded optimism,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

One reason for hope: The likely causes of the spike in murders in 2020 and 2021 are receding.

Disruptions related to Covid probably led to more murders and shootings by shutting down social services, which had kept people safe, and closing schools, which left many teens idle. … But the U.S. has opened back up, which will likely help reverse the effects of the last two years on violent crime.

The aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in 2020 also likely caused more violence, straining police-community relations and diminishing the effectiveness of law enforcement. That effect, too, has eased as public attention has shifted away from high-profile episodes of police brutality. A similar trend played out before: After protests over policing erupted between 2014 and 2016, murders increased for two years and then fell.

There may be several reasons the positive trend has escaped notice. For one, the decrease is small and could easily reverse itself in the last five months of the year. The Times article postulated that negative media bias—the “if it bleeds, it leads” theory—could be another reason. In addition, police departments across the country are under severe strain caused by shortages of police officers.

The Associated Press reported that Los Angeles is down 650 officers compared to prepandemic staffing levels. Portland, Oregon has lost 237 officers through retirement and resignation. Chicago has 1,300 fewer officers than they budgeted to have.

“We’re getting more calls for service and there are fewer people to answer them,” Philadelphia Police spokesperson Eric Gripp told the AP. “This isn’t just an issue in Philadelphia. Departments all over are down and recruitment has been difficult.”

The problem is not isolated to the biggest cities. Reports from Whittier, California; Alpharetta, Georgia; and Deming, Oregon, show the issue is widespread across the country.

As a result, the AP reported, police departments have had to change the way they police: “Many have shifted veteran officers to patrol, breaking up specialized teams built over decades in order to keep up with 911 calls.” The article described how the changes affected the Los Angeles police department, which disbanded its animal cruelty unit and reduced forces on human trafficking, narcotics, and gun details.

The AP and CNN reported that police departments have adopted bonuses and stepped up recruitment to wider areas among other tactics.

In an editorial in the San Diego Union-Tribune, former San Diego office Manuel Rodriguez provided additional recruitment and retention strategies, including childcare facilities for officers working night shifts and “providing tenured officers the opportunity for professional development to gain experience in other areas of the agency by allowing them to work specialized assignments for a two-week period.”