Pay Attention!

How can human operators avoid becoming exhausted on the job, or stay alert while driving for long periods of time? How can security guards ensure that they don’t miss a critical alert during a long shift?

The Human Factors and Applied Cognition program at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, is conducting vigilance fatigue testing with subjects to find out more about how and why mind power becomes depleted, and how to best replenish it. Subjects at the institution’s Arch Lab are given a variety of tasks to perform in a range of scenarios.

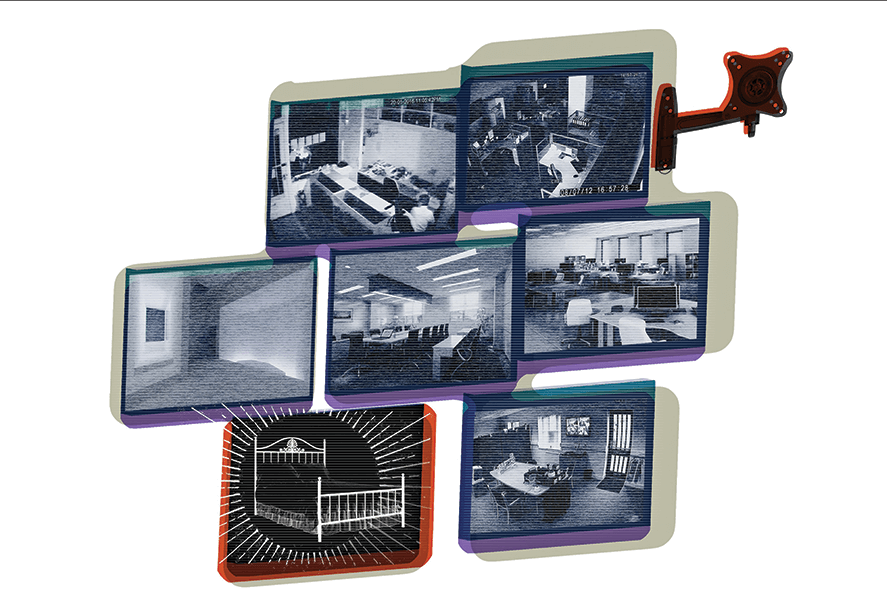

“We are constantly having people do many different tasks at the same time,” says Carryl Baldwin, director of the program. “In one of the scenarios, they are doing five different tasks at the same time, trying to alternate their attention back and forth between three different screens.”

Baldwin explains that vigilance fatigue occurs when our brains become overwhelmed by the task we are performing. “The leading theory of why you experience this vigilance decrement is because your cognitive resources become depleted,” she says. “And we asked, ‘If that’s the case, how do we restore those resources?’ So we started a series of experiments, many of which are ongoing, looking at what can we do to try to bring that person back up to speed, to try to alleviate that performance decrement.”

One hypothesis, Baldwin notes, is that letting one’s mind wander—which is also known as engaging the default mode network—helps restore blood flow to the part of the brain that engages in completing a task, the dorsal attentional network. “This theory is called the decoupling hypothesis, which is that we cycle back and forth between two major attention networks,” she says. “You have to cycle back and forth between those in order to sustain performance for any length of time.”

In a field such as security, Baldwin notes that the lack of incidents that occur during any one shift can lead to increased fatigue, just as with any task where there are little to no stimuli for the brain. “How do you stay motivated to watch screens if, shift after shift, nothing happens?” she says. “You’re likely to miss the signs, because it’s difficult to pay attention when you so rarely get signals.”

The researchers are working on replenishing subjects’ effectiveness at performing a task with a variety of techniques. “One of the things you can do in vigilance research is periodically insert false alarms...to revive the subjects,” Baldwin says. “Because if they’re waiting for a signal that doesn’t happen during a whole eight-hour shift, it’s really tough to stay engaged.”

Offering rewards can also help subjects stay on task. “We’re experimenting with giving people rewards once in a while…primarily to increase dopamine levels, which we think will, in turn, increase their ability to sustain attention on the task.”

Baldwin says simply being in a good mood also appears to promote the subjects’ effectiveness and alertness. “We’ve looked at playing music of a certain type, particularly positive-affect, slow music that’s popular and enjoyable—and people like it,” she says. “That tends to promote relaxing and having a positive attitude.”

CYBER FATIGUE

Fatigue also affects those who make security-related decisions. Most computer users in the United States feel “overwhelmed,” “resigned,” and “hopeless” about the security and privacy of their online behavior, leading them to make poor cybersecurity decisions. That’s according to research by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in an October 2016 study, Security Fatigue.

The authors of the report tell Security Management that they didn’t necessarily set out to draw conclusions about security fatigue in their research, but wanted to learn more about the typical computer user’s online security behavior. “We were really trying to understand people’s perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors with respect to cybersecurity,” says Mary Theofanos, computer scientist at the NIST Office of Data and Informatics.

Theofanos, along with coauthor Brian Stanton from the NIST Visualization and Usability Group, interviewed people ranging in age from 20 to 69 from rural, urban, and suburban areas of the United States. They asked questions such as: What do you do online? How often do you change your password? How do you feel about cybersecurity?

“As we started talking to them, there was just this overwhelming sense of resignation, loss of control, fatalism, and decision avoidance,” Theofanos says. “As we started really pursuing this, we realized these are the characteristics of security fatigue.”

The following were some of the signs of cybersecurity fatigue observed by the researchers:

• Avoiding unnecessary decisions

• Choosing the easiest available option

• Making decisions driven by immediate motivations

• Behaving impulsively

• Resignation and loss of control

Stanton, a psychologist, says that users are tired of constantly being asked to change their passwords, conduct system updates, and engage in other basic cybersecurity hygiene best practices.

“When you reach a certain threshold, you don’t have any more capacity to deal with things, and that’s what we were seeing in the security realm,” he explains. “People didn’t have the capacity to make any more decisions about security.”

Being overwhelmed leads users to make poorer decisions, such as not changing their passwords or updating their machines, or failing to safeguard personal information, opening them up to possible cyberattacks or data theft.

Positive reinforcement, one of the classic ways to fight vigilance fatigue, isn’t necessarily available in the cyber world. “It’s hard to get that reward in the cybersecurity space because there’s no direct cause-and-effect relationship,” Theofanos says. For example, if users change their passwords every 30 days, but they get hacked anyway, they will feel as if their security practices didn’t protect them and are, therefore, not worth doing.

“In cybersecurity you don’t get any feedback if you do it right,” Stanton adds.

Those interviewed also believed that hackers would never target their information in the first place, because they don’t believe they possess anything of value. They stated that someone else should protect their data, such as the bank issuing their credit cards or their employer.

To combat the issue of security fatigue, the research suggested companies take a few steps to ensure that users don’t feel overwhelmed:

• Limit the number of security decisions users need to make

• Make it simple for users to choose the right security action

• Design for consistent decision making whenever possible

Theofanos says that users are aware of the existing cyberthreats, and many mentioned high-profile hacks in the news. Still, she says that good cybersecurity has to become a habit, and awareness isn’t enough. “They can’t fall back on a set of habits, because they haven’t formed those habits. It’s the whole concept of practice, practice,” she says. “It’s a bigger step than just greater education and awareness.”