Radioactive Remedies

In 2013 and 2014, there were 325 reported incidents of lost, missing, or stolen nuclear and radioactive material worldwide. And about 85 percent of those incidents involved non-nuclear radioactive material, which is used to make dirty bombs, according to the 2016 Radiological Security Progress Report by the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

In recent years, the fear that a terrorist would detonate a dirty bomb—use conventional explosives to blow up radiological material—has outpaced concerns about a full-scale nuclear bomb, because nuclear materials are so heavily regulated. Radiological material, on the other hand, is used in more than 100 countries around the world for research, agriculture, and life-saving medical procedures in hospitals. While a dirty bomb wouldn’t cause destruction on the scale of a nuclear weapon, it would contaminate property, cause fear and panic, and require costly cleanup, in addition to the damage caused by the conventional explosion. This type of bomb is appealing to terrorists because it adds a negative psychological response to the normal destruction of an explosive, according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

The NRC, along with partners in 37 U.S. states, licenses, monitors, tracks, and enforces security regulations for nuclear and radioactive material to protect those who work with the material and the public from potentially harmful exposure.

A July investigation by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) led the NRC to strengthen its licensing processes after the GAO was able to obtain a license under false pretenses and purchase a dangerous quantity of radioactive materials—for the second time in less than a decade. (See November 2016’s “News and Trends” department for more on this issue.)

After researchers alerted NRC officials about their investigation, the organization began making corrective actions, including enhanced training, increased scrutiny during site visits, and evaluating license verification.

This isn’t the first time the NRC has made significant changes to its practices due to a GAO report. In 2012, the watchdog organization focused on radioactive materials in medical facilities—a unique environment because, unlike research facilities, medical facilities are open to the public and don’t have the hardened environment inherent in facilities dedicated to working with high-risk materials.

Medical facilities use material produced in nuclear reactors to treat cancer and blood diseases. These uses create another unique threat: the materials are often sealed in metal capsules small enough to be portable. “In the hands of terrorists, these sealed sources could be used to produce a simple and crude but potentially dangerous weapon, known as a dirty bomb, by packaging explosives with the radioactive material for dispersal when the bomb goes off,” notes the 2012 report, Additional Actions Needed to Improve Security of Radiological Sources at U.S. Medical Facilities.

Daniel Yaross, CPP, who sits on the ASIS International Healthcare Security Council, has worked in the healthcare security field for more than 15 years and understands the importance of adhering to NRC regulations to secure nuclear materials. He recalls when the 1,503 U.S. hospitals and medical facilities holding nuclear materials had to update their security practices—at times a costly undertaking—to comply with the newly released NRC standards in 2012.

“Finance could be a hurdle that slows down the progress of providing enhanced security and safety for protective materials,” Yaross tells Security Management.

Yaross notes that it can be expensive for medical facilities to comply with NRC regulations, especially after the overhaul in 2012, which required biometrics updates and constant monitoring. At the time, the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) had spent more than $100 million in helping hospitals meet NRC compliance. NNSA has reported that, due to the expense of the upgrades, the 2012 mandate will not be completed until 2025.

The NRC agreements with their U.S. state partners require that states adopt regulations that are compatible with the NRC’s. Hospitals in these states will be visited biannually to make sure they are compliant with the regulations. Based on the most recent NRC regulation updates, licensed medical facilities are required to ensure security when the radioactive material is being transported; secure the material once it is at its designated storage location; maintain records of transfer and disposal of any radioactive material; and conduct physical inventories of the material.

After the 2012 GAO report, the NRC has provided more specific guidance to licensed facilities, including how cameras, alarms, and 24-hour human monitoring should be implemented. The regulations also specify how radioactive material should be transferred, who is allowed to access sensitive machinery, and what type of storage is required.

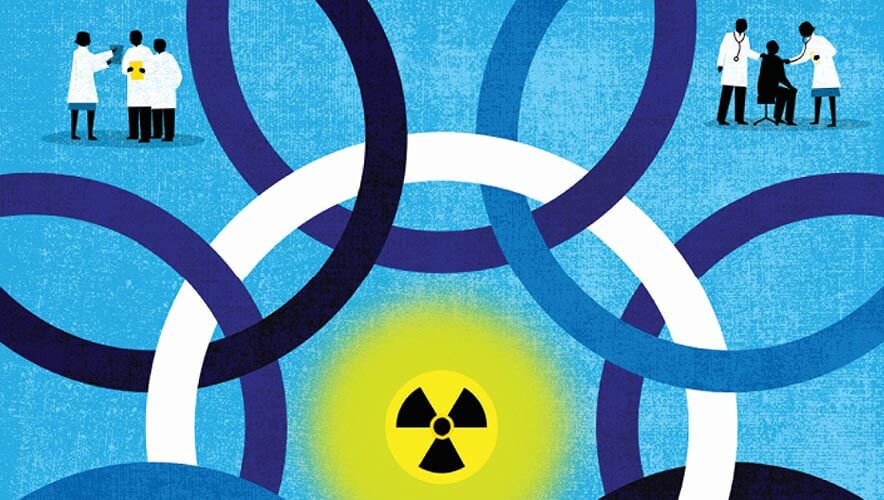

“When we look at nuclear compliance, just like anything else in our security world, it’s not just physical security but cybersecurity too—it’s concentric rings of defense,” Yaross says. “That’s how we handle security for these nuclear materials: concentric rings to make it harder and harder for someone who does not have the authority to get into that specific area unaccompanied.”

Those rings of security typically include basic security measures such as perimeter security and access control, as well as specified measures such as round-the-clock surveillance of the radioactive material and a dedicated radiation safety officer, which are all dictated by the NRC.

While most nuclear materials in hospitals are hidden in plain sight—as small masses of radioactive material buried in large, complicated machines—Yaross says the main goal is to reduce unaccompanied access as much as possible. To this end, the insider threat is taken seriously—few people are allowed to access the radioactive materials unaccompanied, which is emphasized in the NRC regulations. Those allowed to have unaccompanied access to sensitive machinery must undergo a full FBI background check going back seven years.

“A big part of the program is ensuring that the first line of defense, the operational side, is not increasing risk to that material by not vetting our employees that we grant unaccompanied access to,” Yaross explains. “We narrow down the number of people of who actually need to gain unaccompanied access into the facility. It includes security and police officers, as well as the lab technicians and the radiation safety officer.”

Yaross says that while the NRC regulations are generally straightforward and proper compliance looks similar at most medical facilities, it’s still important to have low-profile, highly targeted security systems and processes dedicated to radioactive materials that also mesh with the rest of the hospital’s security standards.

“Most people don’t even know it’s there, and frankly, most would not have a clue of how to access it, or how to separate the material from the actual piece of equipment,” Yaross explains. “Again, we have so many concentric rings of security, it gets harder and harder to get through each layer. That’s not just technology but background and operational procedures, such as how the floor plan is laid out.”