The 90-Character Alert

Shortly before 8 a.m. on Monday, September 19, an untold number of New Yorkers were jarred awake by an unusual tone emitting from their cell phones. Passengers on subway cars looked around uneasily as dozens of phones buzzed and sounded off in unison. A short, text-message-like alert had appeared on the screens of every phone in the range of New York City’s cell towers: 28-year-old Ahmad Khan Rahami was wanted in connection to the explosion in Chelsea earlier that weekend. “See media for pic,” the short alert stated. “Call 9-1-1 if seen.”

Within three hours of the smartphone broadcast, Rahami was spotted by a local business owner and captured after a shootout with police. While it’s currently unclear whether the emergency alert was the factor that prompted the citizen to notify the authorities about Rahami, the New York Police Department and federal emergency management officials were pleased with the alert’s success. It’s the first time this type of broadcast, called a Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA), has been used to notify citizens about a wanted suspect on a mass scale.

“I think the alert system is very helpful to the police department and the FBI,” New York City Police Commissioner James O’Neill said during a press conference. “It gets everyone involved. If we can get everyone in the city engaged to help us keep it safe, this is the future.”

The technology behind the alerts, however, is nowhere near the future. In fact, it was engineered to work for the cellular networks of 15 years ago, according to U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) investigators. Last December, the S&T released a 157-page publication, Opportunities, Options and Enhancements for the Wireless Emergency Alerting Service, with research conducted by three Carnegie Mellon University Silicon Valley (CMU-SV) electrical and computer engineering professors.

The WEA, which was first deployed in 2012, is an effort supported by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the American wireless communications industry. It is designed to alert people of imminent disasters or emergencies. Mobile users are automatically enrolled to receive WEAs, which are typically AMBER alerts to locate a missing child, imminent threat alerts such as natural disasters, or a presidential alert, which has never occurred. The 90-character alerts are geographically targeted and sent out by federal, state, or local emergency management officials through a FEMA portal. Users can unsubscribe from imminent threat and AMBER alerts, but not presidential alerts. The S&T research focuses on leveraging modern technology to make the alerts more useful and actionable, and to reduce the number of people who unsubscribe from them.

Although they look like text messages, WEAs are delivered via broadcast through wireless carriers and transmitted from targeted cell towers to reduce the strain on the wireless networks themselves, explains Bob Iannucci, distinguished service professor at CMU-SV. “The way that WEA was engineered was to conserve bandwidth,” he explains. “You couldn’t send out a million SMS messages in a timely way, so instead the messages are sent via broadcast. What the networks were capable of 15 years ago for broadcast was very limited, and nowadays it’s much more possible with rich media.”

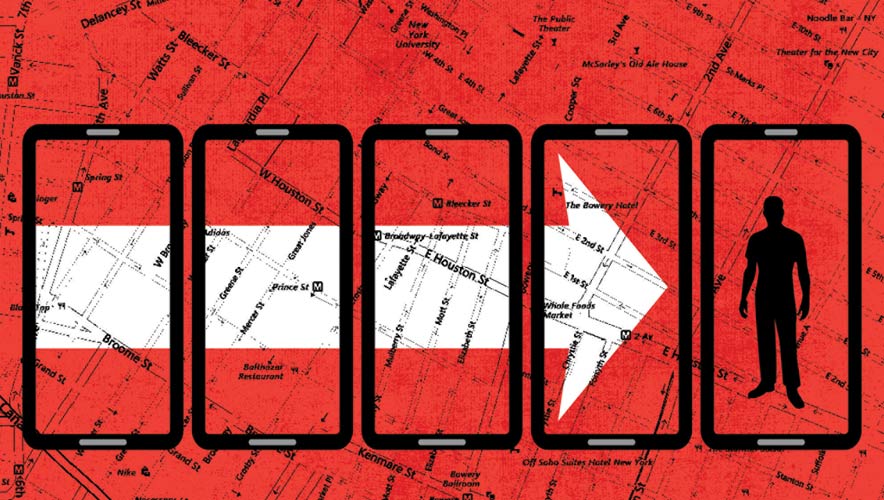

The researchers studied what it would take to send longer alerts that include pictures, links, and even interactive maps, and found that the technology is readily available. Currently, smartphones have built-in software that will activate within range of targeted cell towers. CMU-SV Principal Research Scientist Emeritus Martin Griss says a default, DHS-approved app would seamlessly bring WEA capabilities into the 21st century.

“The idea is by using the app mechanism, we could have much more powerful and rapidly evolving tools, while the current mechanism has to be installed on deck by the phone providers, and improvement can take a long time,” Griss explains.

The researchers built a test app with enhanced WEA features. Beyond more detailed information, the researchers found that an app-based alert system could present the messages in a more easily-understood format. It’s not unusual for multiple WEAs to be sent out with updated information, such as shelter-in-place messages during a natural disaster, followed by evacuation notices based on secondary events. “Such a barrage of messages, particularly bearing updates and changes of strategy, require individuals to receive and digest them in the time sequence, maintain a mental model of the latest instructions, and be able to recall these when acting,” the S&T report notes. Instead of individual messages, an app-based alert system could display only the most recent directives to avoid confusion.

“The basic idea is to build on mechanisms that are already part of the standards and part of cell phones, rather than going through a lengthy process of reengineering a broadcast mechanism,” Iannucci notes.

The researchers touched on even more expansive abilities with the proposed app-based mechanism. With smartphone technology, it’s possible for the alerting system to dispatch messages based on a user’s current physical activity. “For example, if a person is sleeping at home after midnight, an AMBER alert may not be relevant or actionable to that user, but a similar message arriving while the person is driving or cycling would be welcome,” the report notes. Location history and prediction can also be leveraged: users who visit a location frequently could automatically receive an alert affecting that location even if they aren’t there.

The use of this data shouldn’t raise privacy concerns because it’s all performed on the client side: “Those actions are done on the user’s phone and the user’s data never leaves the phone,” explains Hakan Erdogmus, an associate teaching professor at CMU-SV. “It’s not like it’s stored in a central server and the phone looks it up—it’s all done inside the phone, because the phone knows its location history, where it is, how far it is from the targeted location.”

Although the CMU researchers conducted extensive testing on enhanced WEA capabilities, they acknowledge that actually deploying those capabilities won’t happen overnight. “The technology is not as complicated as the agreement to use it,” Griss notes.

While wireless carriers voluntarily participate in the program, smartphone manufacturers have less say in the process. Iannucci explains that manufacturers build the WEA software into their phones to comply with the carriers. A more robust WEA system will put even more of a burden on manufacturers, he says.

“It’s a bit of a challenge to engineer this as a well-thought-out end-to-end system where there’s a clear stakeholder and everybody along the chain can perform,” Iannucci says. “Current phone manufacturers are doing what’s required, and we’re arguing for a bit of a higher standard of end-to-end engineering this system for the public good.”

The FCC issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking last November to expand WEA capabilities, although no platform—app or built-in software—was specified. The issuance included a window of time for stakeholders to comment on the proposal, and Erdogmus notes that many major smartphone manufacturers and carriers responded.

“If you go through the responses, you get the feeling that they’re pretty unwilling to do more than they’re doing right now, even for simple changes that are very feasible,” Erdogmus explains. “That’s why a third-party app could encourage innovation, because otherwise it’s not going to happen easily without some kind of enforcement.”

Carriers and manufacturers have liability concerns, too. Griss notes that these stakeholders have questions about what happens if a customer doesn’t get a WEA. “What are they actually responsible to do? Is it to guarantee delivery in a particular area? To wake you up?” he asks. All of these concerns will have to be addressed at length with the FCC, FEMA, and private industry stakeholders before WEA capabilities can be expanded.

“With our experiments, we are proving the feasibility of it all,” Erdogmus says. “The rest boils down to politics and how to draw up agreements and which parts will be enforced, which parts will be voluntary, and who takes responsibility and so on, which is the hardest part.”

There are bigger questions to answer. If the WEA system gains the capabilities the researchers imagined, what is the overall role of the system during an imminent threat? Is it to alert citizens, or to guide them during a crisis?

The report found that while some people think of WEA messages as “bell ringers” that rely on the public to use other communication channels to obtain additional information, others believe WEAs should be augmented with additional information and effective incident follow-up.

There’s also the matter of whether WEAs should be more integrated with social media. In one test, a WEA sent out regarding severe weather did not increase the frequency of weather-related posts on Twitter, which is indicative of poor WEA effectiveness as compared with social media, the report notes. Many alert originators are using both social media and WEAs to alert their communities of threats, and citizens desire WEA messages with links or hashtags for more overlap with traditional forms of social media, the report explains. The researchers recommend the usage of simple hooks, such as hashtags or other forms of outside engagement, to further the reach of WEAs.

“We say that WEA is part of the social media pantheon and has this nice alarm bell characteristic that other social media don’t,” Iannucci says. “It’s not an either–or, it’s how the two systems complement each other.”

The researchers noted that September’s WEA in New York contained a simple hook by telling recipients to consult media outlets for a picture of Rahami. However, Iannucci wonders whether the command backfired. “The challenge there is that in a large population, if everyone gets the same ‘see media’ message at the same time, it has the potential to cause serious network issues when everyone tries to browse the media at the same time,” he notes. “We won’t see the statistics for a while, but it will be very interesting to see what happened to network traffic in the 30 to 60 seconds after the alert went out.”

If the WEA had the capability to include a picture of Rahami, it would have been easier on both users and the network, Iannucci notes.

“Because the message was short, people tend to validate what’s going on by checking around,” Griss explains. “They talk to friends, they look at social media. People are already using several kinds of media to keep track of whatever is happening. How you coordinate those two needs to be thought through.”

Even though the New York message showed the shortcomings of the WEA system, the researchers said it was an important use case that could bring to light the issues they wrote about last year.

“My feeling is this will prompt similar usage of WEA more broadly” for wanted suspects, Iannucci says. “Because of its visibility, it will probably encourage broader use of WEA which is wonderful. That’s when we can raise the subject of how we further enhance it once there’s greater awareness of its value.”