Frozen Progress: Building Winter Storm Continuity in Texas

“It’s as easy as turning on the lights.” Although it’s a common phrase, the ability to turn the lights on is not easy. And in recent years, extreme climate events have exacerbated the intricacies involved in delivering utilities, like power, to homes and businesses.

Texas is no stranger to extreme weather, including intense heat and record-breaking hurricanes. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), electricity generation usually peaks in Texas during the summer. The annual spike is triggered by residents firing up air conditioners in search of some respite from rising heat—in some areas of Texas, temperatures reached 116 degrees Fahrenheit in 2020.

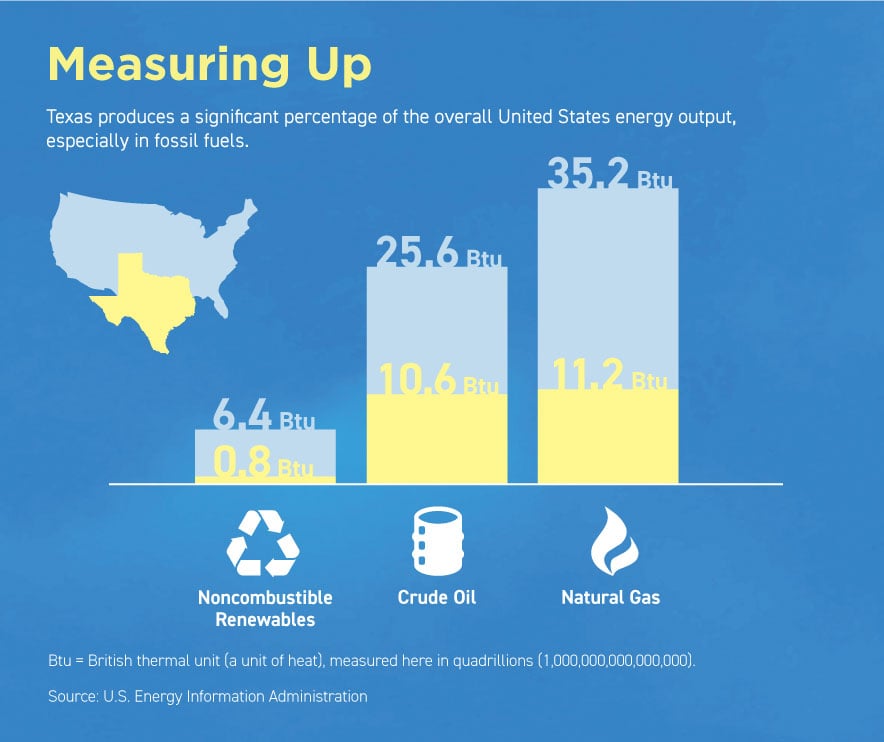

And the U.S. state usually has energy to spare. In the United States, energy production is largely dominated by fossil fuels, which include crude, natural gas, and coal. Texas is not only the U.S. state responsible for producing the most energy but also the largest energy-consuming state, according to the EIA.

Another unique feature of Texas’s energy profile is that it is the only continental U.S. state with an independent energy grid. The rest of the continental U.S. states and Canadian provinces are combined into two synchronous grids: the Eastern Interconnection and the Western Interconnection.

But in February 2021, a seemingly singular strain on Texas’s power grid occurred. With a polar jet stream and polar vortex generating winter storms, Texan grid operators faced an unusual surge in demand for midwinter power—one they were not prepared for.

Stormfront

A battering ram of severe winter storms knocked on Texans’ doors in mid-February 2021, part of one of the most significant winter seasons that most of the United States has experienced in recent years. Although much of the country experienced a milder winter on average in 2021, Winter Storms Uri and Viola stretched across parts of the United States, as well as northern Mexico and some of Canada. Uri alone triggered power losses from North Dakota to Texas, while Viola left 4 million people in the Deep South and part of the Southeast without power, exacerbating the blackouts in Texas.

A battering ram of severe winter storms knocked on Texans’ doors in mid-February 2021, part of one of the most significant winter seasons that most of the United States has experienced in recent years. Although much of the country experienced a milder winter on average in 2021, Winter Storms Uri and Viola stretched across parts of the United States, as well as northern Mexico and some of Canada. Uri alone triggered power losses from North Dakota to Texas, while Viola left 4 million people in the Deep South and part of the Southeast without power, exacerbating the blackouts in Texas.

Beginning on 10 February, the first of three storms started dropping sleet and ice and pushed the temperature down in Texas and other southern U.S. states. Altogether, the storms resulted in a record-setting low temperature for Texas: -2 degrees Fahrenheit (-19 degrees Celsius), the coldest weather in North Texas since about 1949.

While Texas produces more energy than any other U.S. state, much of its infrastructure is not winterized. This became a problem when Uri rolled in on 13 February and the temperature dropped into single digits, causing equipment to seize, tripping generating units offline, and halting operations. Two days later, approximately 2 million homes and businesses did not have power in Texas. By the following day, at least one in 10 power plants were shut down and more than 3 million outages were reported, with each outage representing a single utility customer—not the actual number of people affected by the blackouts. On 17 February, Viola began developing off the Texas coast, bringing in freezing rain and ice and worsening attempts to fix the grid’s faults.

Altogether, the storms triggered massive power losses that lasted days throughout wide swaths of the U.S. state. Hospitals were left to rely on emergency generators, while road conditions left some people stranded, caused colleges and universities to cancel classes, and hindered emergency responders.

The demographics of vulnerable people shifted during these storms. Homeless populations were at high risk, but the below-freezing temperatures also impacted people and families who had shelter. Families without power elected to sleep in their cars or in mobile warming stations instead of freezing homes.

“Low-income Texans of color bore some of the heaviest weight of the power outages as the inequities drawn into the state’s urban centers were exacerbated in crisis,” the Texas Tribune reported.

Others at a higher risk of death during power outages due to extreme cold temperatures included medically vulnerable people, including those suffering from chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and kidney disease, who may need to keep medication at specific temperatures.

Some Texans recovering from COVID-19 were dependent on home oxygen equipment intended to assist still-healing lungs, but during the power outages, the machines were effectively non-operational. Some patients had portable oxygen tanks that could act as a stopgap for a typical 45-minute rolling blackout, but when outages stretched out for days, those resources wore thin, endangering lives further.

Texan Power Roundup

The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) is the independent system operator for the Texas Interconnection, responsible for delivering power to 26 million customers through more than 46,500 miles of transmission lines, plus power plants. ERCOT operates and monitors the grid to maintain a crucial frequency balance of electricity flow along the system, but it does not own individual components of the grid—including power plants, transmission lines, or the demand for electricity.

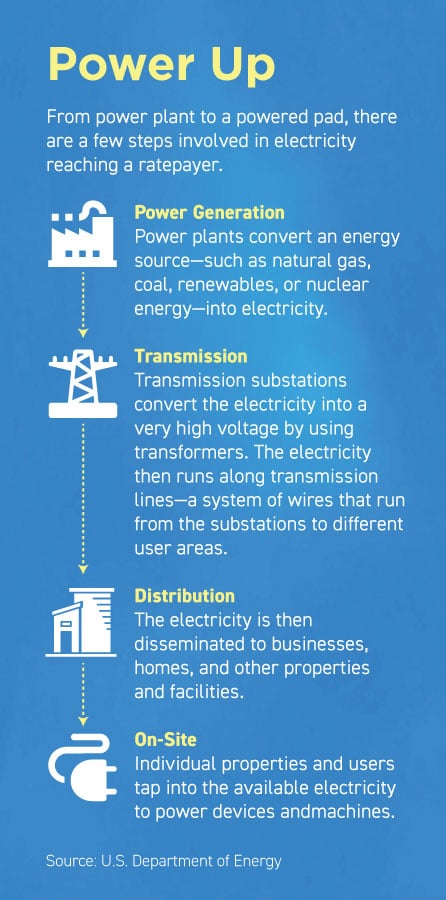

In some ways, supplying electricity is like walking a tightrope, or perhaps a transmission line: it’s a process that demands constant balance. Essentially, the amount of power supply on a grid must match the demand for power from ratepayers, so grid operators must predict how much electricity to generate at a time. Too much supply and not enough usage or demand can cause an increase in electrical frequency, which can disconnect, or “trip off,” a power plant that operates within a certain frequency range. Not enough supply and too much demand can trigger a domino effect, first tripping off one power plant and then another and another, ultimately causing a blackout.

“Weather conditions—particularly Texas’s triple-digit summers—are a huge factor in predicting demand, since about half of Texas’s peak electricity use comes from air conditioning,” the office of Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar said in August 2020, adding that ERCOT was confident there was sufficient supply to provide power throughout the summer.

That summer power supply mainly comes from natural gas. It produces as much as 61 percent of Texas’s energy during peak summer demand. Winter, however, is a different story. Power plants in Texas typically do not contract for a large winter purchase because the average temperature is 45 degrees Fahrenheit (7 degrees Celsius) for most of the season. Having a large amount of natural gas on hand is usually unnecessary.

So, when the 2021 winter storms hit, not only were power plants and plant equipment strained by the extreme cold, but they lacked additional natural gas supplies. To try to bolster power supply to meet the heightened demand as Texans cranked up the heat, Texas Governor Greg Abbott ordered natural gas producers to only sell supplies to energy providers within Texas—prohibiting them from exporting gas supplies outside of the state until 21 February. But natural gas facilities were hit by power outages too, and the plants could not produce gas supplies if they were offline.

The storms’ cloud cover and snow also limited solar farms’ output, according to Bill Magness, former CEO of ERCOT, while wind power and coal plants were also tripped offline by the extreme temperatures.

By 15 February, ERCOT started intentionally shutting down parts of the grid to prevent a more severe power outage. Its goal was to provide power to priority users, such as hospitals and fire stations, while rotating service to all other ratepayers so they would not be without power for more than 45 minutes.

If ERCOT had not taken the step to initiate rolling blackouts, the increasing demand from ratepayers would have strained the remaining operational equipment to the point that it would have ignited. This would have caused downed power lines and blown out power substations, said Magness in a late-February hearing before the Texas State Senate Business and Commerce Committee. Repairing this damage, he added, would have taken months.

“It’s our job to keep the grid balanced, and if I’m looking at it, the problem was at the sites of the various generation,” Magness said.

Before February 2021, there had only been three systemwide rotating outages under ERCOT—December 1989, April 2006, and February 2011.

“Rotating outages are only used as a last resort to bring operating reserves back up to a safe level and maintain system frequency,” ERCOT explained in a 2020 public notice. “Rotating outages primarily affect residential neighborhoods and small businesses and are typically limited to 10 to 45 minutes before being rotated to another location.”

Instead, in February 2021 more than 5 million people were without power as power infrastructure tripped offline. Some people lost power for more than three days.

When Texas began deregulating its energy market in 2002, one of the results was that the grid and power companies within the state became isolated from federal oversight. Instead of a single company owning all or a majority of grid facilities—from generator plants to distribution networks and transmission lines—several individual companies operate as generators and transmission operators, selling the energy they create and transport on a wholesale market further downstream. Power distribution companies can buy the energy and then resell it to ratepayers, such as homes and businesses.

With this more granular structure, once their facilities began tripping off, individual power plants struggled to find nearby additional energy supplies. During the storms, Abbott, with support from U.S. President Joe Biden, reached out to neighboring U.S. states in search of supplementary power supplies but with little success as the governors of Louisiana and Oklahoma were also struggling to maintain their own grids.

Although the storms were gone by 20 February, reporting their full impact and the consequences of a lack of electricity throughout Texas continued well into 2021. In July, total official fatalities reached 210; most of the confirmed deaths between 11 February and 5 March were linked to hypothermia, while other causes were listed as carbon monoxide poisoning, exacerbation of a chronic disease, falls, fire, and motor vehicle collisions. However, there has been at least one independent analysis that suggested the state might have undercounted the death toll, with deaths suspected of being triggered by the power outages and cold instead attributed to natural causes.

Besides deaths, Texas experienced other impacts from the widespread power loss, including disruption of water service. Without power to maintain heat, pipes froze and burst, and some fire hydrants were unusable to assist in emergency services. About half of the state’s residents were without water, and roughly 12 million other Texans—in areas including Austin, Corpus Christi, Houston, and San Antonio—had low water pressure and were under boil-water advisories. Residents in San Antonio were seen along the River Walk collecting buckets of river water so they could flush their toilets.

Food and grocery supply chains were also hampered by the storms and the power outages, with stores either unable to remain open due to a lack of power or unable to resupply their shelves.

In the aftermath of the storms and outages, power companies found themselves in a tough spot, too, having to pay ERCOT for replacement power sources when their own facilities shut down. Brazos Electric Power Cooperative, the oldest and largest power co-op in Texas, filed a Chapter 11 bankruptcy petition in February after receiving a bill for more than $2.1 billion.

Beth Garza, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute, a think tank that specializes in policy research, notes that other Texas power companies are investing money in hardening their infrastructure despite the hefty bills. One example she points to is Vistra Corp., which claimed to have lost about $1.6 billion because of the February freeze; however, it also announced plans to invest in alternative fuel storage at some of its plants and other backup fuel options, such as increasing the amount of underground natural gas storage that it leases.

Power companies are not the only ones shoring up their infrastructure. Although some hospitals remained operational during the 2021 storms, others only did so by relying on their emergency generators, which are required by the Texas Department of State Health Services to have enough fuel to power their facilities for 96 hours. Other medical facilities were also hindered by the water shortage because certain equipment and procedures—like hand washing before surgery—

depend on clean water.

While healthcare providers faced obstacles to care for patients inside hospital facilities, first responders in ambulances came across literal roadblocks to the people they were trying to reach since many roads in Texas were not cleared during the storms or soon after. Roadblocks also kept some Texans from traveling to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, which, according to a Texas health official, resulted in the destruction of approximately 1,000 unused vaccine doses.

Déjà Vu

Criticism of Texas’s grid management quickly flourished, especially when it emerged that ERCOT had not established best practices recommended by the U.S. federal government, such as utilities winterizing their facilities. The recommendations were included in a report released nearly 10 years before, after a 2011 blizzard caused power outage issues throughout Texas.

In February 2011, cold temperatures from the blizzard led to ERCOT initiating rolling outages in an attempt to curb the increased demand that risked overloading the grid. The storm’s extreme temperatures—falling as low as -2 degrees Fahrenheit, with the wind chill pushing it down to -16—caused issues for more than 150 generator facilities, created road hazards, impacted water utilities prompting a boil-water advisory, and froze or tripped off some natural gas facilities.

Prepared and published by the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), the Report on Outages and Curtailments During the Southwest Cold Weather Event of February 1-5, 2011, explored the causes of the power outages and made recommendations to ERCOT.

“Going into the February 2011 storm, neither ERCOT nor the other electric entities that initiated rolling blackouts during the event expected to have a problem meeting customer demand. They all had adequate reserve margins, based on anticipated generator availability,” the report said. “But those reserves proved insufficient for the extraordinary amount of capacity that was lost during the event from trips, derates, and failures to start.” (Derating occurs when power plants and equipment function at less than the maximum capability, which can occur if the equipment is not winterized and subject to extremely cold temperatures.)

The 357-page report noted that capacity losses for power generators and natural gas producers during the 2011 blizzard were tied to inadequate winterization.

“While extreme cold weather events are obviously not as common in the Southwest as elsewhere, they do occur every few years,” it noted. “And when they do, the cost in terms of dollars and human hardship is considerable. …This report makes a number of recommendations that the task force believes are both reasonable economically and which would substantially reduce the risk of blackouts and natural gas curtailments during the next extreme cold weather event that hits the Southwest.”

Because the Texas grid is operated independently of the other national interconnections, however, it was left to ERCOT’s regulator, the Texas Public Utility Commission (PUC), to implement and enforce FERC and NERC’s recommendations. Ultimately, state officials left the choice on whether to winterize—an extremely expensive upgrade that ensures equipment can withstand below-freezing temperatures for protracted periods, which are rare events in Texas—up to individual power companies. Many of them decided not to upgrade.

In September 2021, FERC and NERC presented a preliminary report on the February 2021 blackouts, February 2021 Cold Weather Grid Operations: Preliminary Findings and Recommendations. This 31-page presentation noted that along with outages within the Texas Interconnection, parts of the Eastern Interconnection also experienced blackouts.

“Freezing issues, which in turn are caused by failure to sufficiently ‘winterize’ the generating units for cold weather conditions, are the largest cause,” the report said, estimating that this accounted for 44 percent of the blackouts in areas managed by ERCOT, Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) South, and Southwest Power Pool (SPP). “Of the 1,823 unplanned outages, derates, and failures to start caused by freezing issues, 1,244 were in ERCOT, 473 were in SPP, and 106 were in MISO South. …As temperatures decreased, the number of generating units outaged or derated due to mechanical/electrical issues increased.”

And this probably will not be the last time Texas and other southern U.S. states encounter freezing issues—in a report published by Science, researchers observed that average temperatures in the Arctic are increasing, similar to most parts of the world. However, reports estimate that the Arctic is warming two to three times as fast as everywhere else. The researchers also noted that a disrupted stratospheric polar vortex (SPV) was linked to the weather pattern that triggered the extreme cold that hit Texas in February. The warmer overall weather diminished the SPV’s typical course enough that it was pushed further south rather than remaining in polar areas, resulting in the February 2021 storms, according to the report, Linking Arctic variability and change with extreme winter weather in the United States.

Even if a winter storm with milder temperatures hits an area, outages can still occur due to rain, sleet, heavy snow, strong winds, or debris that damages equipment or infrastructure, such as fallen branches or trees. In late February and early March of 2018, four winter storms fell upon the northeast region of the United States from Maine to Washington, D.C., and they resulted in power outages for more than 2 million people.

While Texas’s ERCOT has only triggered system-wide rotating blackouts four times, this does not mean that other winters lacked close calls. Severe cold in January 2014 resulted in some power plant equipment tripping off and interference with other components, diminishing overall power plant generation. The decreased electrical supply had ERCOT asking ratepayers to reduce their own energy use as grid operators were considering implementing rotating blackouts.

Blackout Backlash

The apparent lack of winterization along grid and gas producer facilities resulted in a string of departures in 2021 as grid operators found themselves under the limelight. By the end of March, seven ERCOT board members—including the chair and vice chair—left, PUC Chairwoman DeAnn Walker resigned, and the ERCOT Board of Directors fired Magness.

Families who either lost family members or were victims of severe harm linked to the power outages filed lawsuits against ERCOT, accusing the operator of ignoring warnings about grid weaknesses. Previous lawsuits against the private company, however, have been dismissed since it is able to claim sovereign immunity as an integral part of the electric grid and energy industry. This legal principle protects agencies from liability because a lawsuit could upset critical government services. In ERCOT’s case, a successful lawsuit against it could not only financially ruin the operator, but also leave this grid without a central management system.

In March 2021, a split Texas Supreme Court turned down consideration of a suit against ERCOT, leaving the council with the ability to continue using sovereign immunity as protection against lawsuits. (Electric Reliability Council of Texas Inc. v. Panda Power Generation Infrastructure Fund LLC, Texas Supreme Court, No. 18-0781, 18-0792, 2021)

A separate class action lawsuit against Texas electric utility Griddy Energy, LLC, revealed that the wholesale power provider charged ratepayers fees as high as $9,000 per megawatt hour (a measure of electrical output from a power plant) for days during the February freezing temperatures. In response to the suit, Griddy filed for bankruptcy, with a liquidation plan that subsequently released its customers from all outstanding balances, according to the Office of the Texas Attorney General. (Texas v. Griddy Energy LLC, et al., Harris County 133rd District Court, No. 21-30923, 2021)

Outside of the courts, Abbott’s office also called on the Texas legislature to make ERCOT reform an “emergency item” and investigate the impacts of the storms to find lasting solutions to the problems that triggered the power outages.

By May, both Texas legislative chambers approved Senate bills 2 and 3, which alter the grid and how it is managed. Abbott signed the bills on 8 June 2021.

Senate Bill 3 requires power generation and transmission companies to not only winterize their facilities, but also upgrade them to withstand extreme weather in general. On the natural gas front, only facilities labeled critical infrastructure by Texas regulators—the Texas Railroad Commission (RCC) for gas facilities and PUC for power—will require upgrades. Although legislators in the House proposed a bill to create a $2 billion plan to help power companies pay for weatherizing with reserve funds, loans, and grants, the bill failed to pass the Senate before the legislative session ended.

Senate Bill 2 alters ERCOT’s structure, cutting the number of directors on the board from 16 to 11. It also creates a selection committee made up of Texas politicians that will appoint eight of the board members. Previously, ERCOT board members were chosen by a nominating committee within ERCOT or appointed by electric market companies. Critics of Senate Bill 2 claim the change will not significantly improve the grid, ousting industry experts for political appointees.

One month after the bills were enacted, Abbott ordered the PUC to take additional actions along the grid, including holding inconsistent generators, such as solar and wind power providers, financially responsible for outages; reorganizing incentives to encourage development of “reliable” energy sources, including natural gas, coal, and nuclear power; creating a maintenance schedule for power providers; and ordering ERCOT to speed up transmission projects to reach underserved areas.

Ready or Not

The 2022 Old Farmer’s Almanac dubbed the 2021-2022 winter a “Season of Shivers,” predicting that the season would be marked by temperatures well below average throughout the United States. “This coming winter could well be one of the longest and coldest that we’ve seen in years,” according to Almanac Editor Janice Stillman. For the region including Texas, predictions ranged from above-average snowfall to frigid cold.

FERC and NERC’s 2021 report called for “careful planning and coordination” when managing these utilities and maintaining reliability for customers, “especially during cold weather conditions when the demand for natural gas and electricity are at their highest levels.” FERC Chairman Richard Glick said that the failure to act upon prior recommendations to weatherize Texas grid infrastructure was a “wake-up call.”

The preliminary report made nine recommendations, largely focused on winterizing grid infrastructure.

“This time, we must take these recommendations seriously, and act decisively, to ensure the bulk power system doesn’t fail the next time extreme weather hits,” Glick said. “I cannot, and will not, allow this to become yet another report that serves no purpose other than to gather dust on the shelf.”

But at the cusp of winter in November 2021, experts were questioning if enough had been done to ready the grid for another storm or for when below-freezing temperatures hit Texas again.

The short answer is: No. The slightly longer answer is: It’s complicated.

After previous significant outages in 2003, NERC developed cold weather standards that have slowly been accepted as good industry guidelines. Following the 2011 blizzard, Texas regulators introduced rules that required power plants to have a winterization plan, annually prove facilities had adhered to it, and keep files on the tests.

“The problem is there’s no requirement that says your power plant has to be prepared to operate when the temperature gets to -5 degrees Fahrenheit,” Garza says, pointing to ambiguity within previous rules and the ones recently adopted by PUC. Recent PUC rules order power plants to address and repair damages caused during the 2011 and 2021 storms, followed by a phase that calls on determining the extremity of weather that plants need to be prepared to deal with. But, according to Garza, that assessment will not be ready in time for the 2021-2022 winter season.

Further frustrating power plant operators is the expense of weatherizing their facilities. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimated that winterizing natural gas and oil wells, which could be a long-term effective solution, would cost between $20,000 and $50,000 per well, or $85 million to $200 million for all of Texas’s wells, every year.

For the power sector, the bank estimated that winterizing all the equipment that FERC and NERC recommended needed the additional protection is likely to cost all 162 gas-powered plants in the state up to $95 million.

For smaller or more marginal power plants that already do not make a hefty profit, the bills paired with the cost of weatherizing can be enough to tempt some to retire, leaving more areas underserved. “That balance…is always at play in trying to develop these standards,” Garza says.

Texas’s supply chain for fuel is also a conundrum. With production sites and shale plays essentially in Texas power plants’ backyards, natural gas has long been considered a more convenient and “less dirty” fuel solution to coal and oil, especially since other components of the gas industry—from transmission pipelines to the downstream facilities, where gas supplies are processed into various products or distributed by a company to consumers—are nearer to various power plant companies. This means a shorter supply chain and fewer costs towards additional or new transportation infrastructure, unlike other natural gas users in the United States who rely on interstate pipelines stretching hundreds of miles to receive their supply.

But despite how close they are to Texas power generators, gas products will not flow in below-freezing temperatures if the equipment trips off. And with Senate Bill 3 limiting forced weatherizing upgrades to natural gas facilities deemed “critical,” some market experts are skeptical of whether the changes to the grid, as well as its suppliers and operators, will ultimately benefit users and power companies.

Garza, however, says she is hopeful that at least some gaps on the power side are being filled in. “I have confidence that (power plant owners) have already started trying to address the issues that came to light,” she says.

Along with dealing with the sources of plant failures, Garza also points to the fact that power plants now have a better awareness of where more natural gas facilities are located and can factor that into curtailment and business continuity plans.

And when the rare occasion arises that demands another intentional rolling outage, power comes back to natural gas. Natural gas companies are encouraged to list their facilities as critical so they can keep their power on even during forced outages. However, that status also means they must winterize their equipment.

The required winterization process is still in its early phases, and it’s worth recalling that neighboring grids and independent system operators were unable to assist ERCOT with additional power. Part of the issue, says Richard Kauzlarich, co-director for George Mason University’s Center for Energy Science and Policy, is the prioritization of a single state over a region when it comes to energy.

It’s unlikely that Texas—which strongly maintains its independence within the energy market—will reach out to become part of other regional systems, Kauzlarich says. Even during the February 2021 blackouts, former Texas governor and U.S. Energy Secretary Rick Perry told U.S. Representative and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) that Texans would rather endure them than see increased federal oversight or involvement in their market.

Along with Vistra Corp. and other power providers investing in backup storage, additional infrastructure, and alternate fuel sources, Kauzlarich notes that having a plan B will be difficult for the region.

“When you think of it at the national level or in an international framework, whether you’re the United States or some smaller country in Africa, you’re going to want diverse sources of energy so if something happens you can fall back on another pattern,” Kauzlarich says.

For this winter, whether the weather is mild or severe in the Southwest, Kauzlarich says that ultimately, “I don’t think there’s going to be any significant change starting this winter over where they were before.”

Sara Mosqueda is assistant editor of Security Management. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter:

@ximenawrites.