Where Does DE&I Stand in the Security Industry?

Diverse teams are stronger teams. This has been proven by scientific research as well as in-the-field practices—bringing in different viewpoints helps to uncover new angles, potential solutions, and pitfalls that a homogeneous group might have missed. The security industry has been making intentional progress when it comes to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) in recent years, but efforts can meet with apathy, nervousness, or fervent opposition in some quarters, especially when they are not adequately supported.

To help security leaders make well-informed decisions about DE&I initiatives and choices, the ASIS Foundation funded an in-depth study, Empowering Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Corporate Security, which was released 18 January 2023. The full report is available for free to ASIS members.

So, why is DE&I so essential for security professionals?

“The security environment that security practitioners find themselves in day in, day out isn’t getting any easier to manage,” says one of the researchers behind the report, Rachel Briggs, OBE, from the Clarity Factory. “We really do need a team of all the talents around the table if we’re going to stand half a chance of being successful against our adversaries.”

But in most cases security has work to do to achieve diverse teams, Briggs tells Security Management. “You don’t really need a study to tell you that the industry isn’t as diverse as it could be. You’ve just got to look around most of the rooms that you find yourself in.” Briggs notes that she has been conscious of this gap for the 20 years she has been working in and around the security industry, which is why she wanted to pursue research into the topic—to provide real, actionable data that can fuel conversations in the industry about “the need for diversity, the benefits of equity, and why inclusive workspaces make for better and more productive places of work.”

Briggs and her research partner Paul Sizemore conducted an extensive literature review, interviewed security leaders across the industry, hosted an anonymous survey of 474 security professionals, analyzed 5 years’ worth of job searches from a security recruitment firm, and conducted structured interviews with 16 chief security officers. They looked specifically at five key dimensions: sex, gender identity, race and ethnicity, disability, and neurodiversity. While age is a significant factor in diversity, the number of varied responses on this topic was limited, so it was excluded in most of the findings, but Briggs says she plans on addressing it in depth in future research.

“One of the great things that the survey showed is that people of many and diverse identities are feeling that they are integrated into the industry,” she adds. “I think that’s one of the positive messages that we can bring out of this, but individuals experience the industry in different ways depending on who they are. I think all of those different identity groups had certain and different ways of perhaps feeling more or less welcome, feeling more or less like they belonged, feeling more or less like they were getting equal access to opportunities and progression opportunities and so on.”

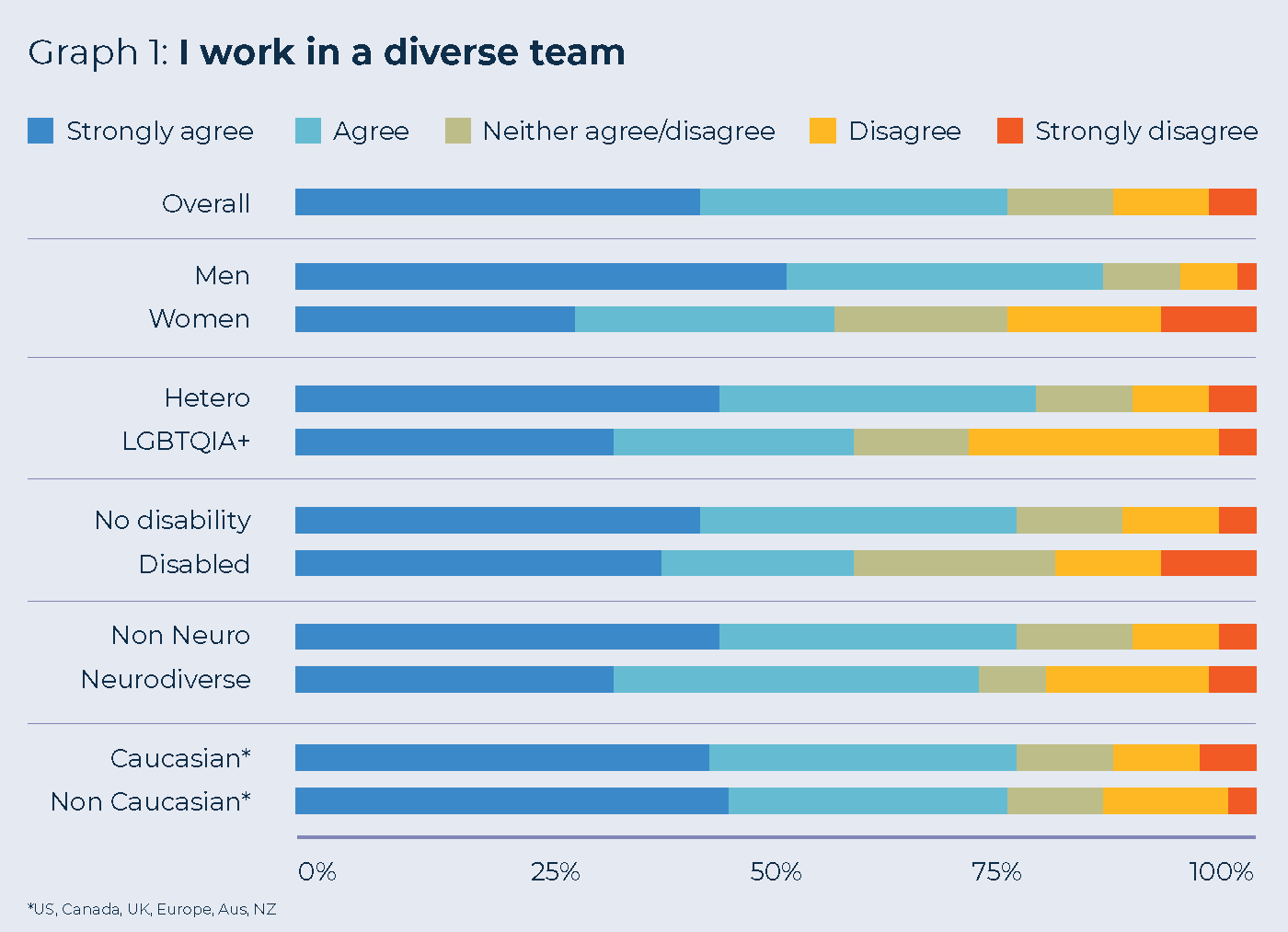

Two of those areas that stood out to Briggs were gender and sexual orientation. “There were some consistently divergent views between men and women answering questions,” she says.

Out of the survey participants, 38 percent were women, and 11 percent identified as LGBTQIA+. When asked the extent to which they agreed with the statement “I work in a diverse team,” 74 percent of all survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed. Among women, however, this dropped off to 56 percent. Among LGBTQIA+ participants, it hit 58 percent. Who strongly disagreed with the statement? 26 percent of women, 30 percent LGBTQIA+, 21 percent with a disability, and only 8 percent of men.

There are unmistakable benefits to investing time, effort, and resources in DE&I—both for employees and for the organization. Briggs cites four key arguments:

Avoiding blind spots. “A homogenous team will result in blind spots,” Briggs says. “If they and their team all look the same, all sound the same, have all got the same background, and so on and so forth, they are not going to understand the world and the threats that it poses in sufficient levels of nuance to be able to really do their job properly for the organization they’re there to protect... That’s weakness in a security program.”

Matching the organization. Security leaders have long advocated having teams that are capable of serving the whole organization and understand the needs of the company. “As DE&I has quite rightly risen up the corporate agenda, the extent to which corporate security departments stand out as being incredibly un-diverse hampers their ability to serve the whole company and be business aligned,” Briggs adds.

This extends beyond internal stakeholders to external perceptions and needs as well. One security intelligence manager who was interviewed for the research report noted that “In a global company where your clients are diverse, if you don’t have a diverse team that can empathize with and understand their clients, think about what this means in terms of how they design their solutions and policies… if you don’t have those people who can see things in a different light and speak to that, you will fall further behind as a function. They’re not going to be cutting edge, they’re not going to be competitive.”

Recruitment. Speaking of competition, the battle to recruit the best talent is taking a turn from money to culture. Younger workers—especially those who belong to Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2012)—value diversity as much as they value salaries when considering job offers, Briggs says. “Chief security officers, as well as heads of HR, are well aware that companies need to be diverse to be able to attract the best talent in the future,” she notes.

Complex and volatile risks. “If you’re going to find a period in time to be a great innovator in the security world, it’s today,” Briggs says. Given the broad global upheaval after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruption caused by multiple cross-border conflicts and wars, the environment where security operates is volatile, and it’s only going to get more complicated.

“The next five to 10 years are going to be marked by and characterized by disruptive innovation with in the security industry,” she says. “It will be the security departments that can disruptively innovate that will really win the corporate security game…. If you don’t have a diverse team, you don’t stand a chance of being able to think as differently as you need to think to come up with a new set of solutions that can cope with what is arguably one of the most difficult security environments that we’ve seen in my lifetime and arguably for many generations.”

So, what is holding people back? The research report includes comments from DE&I detractors and critics, as well as supporters, to give a more accurate picture of the issue in the industry today. Briggs finds that people who are less enthusiastic about DE&I generally fall into three broad categories:

Anti-DE&I. On the furthest end of the spectrum, a small minority of survey respondents expressed anger and disdain about DE&I efforts—inside organizations, from industry associations, and in culture more broadly.

Nervous. There was a contingent of security professionals who recognize the value of diversity but are worried about saying or doing the wrong thing.

Concerned about balance. Some security professionals surveyed said that DE&I is valuable but the pendulum has swung too far, and efforts are a bit out of focus.

“For those who are nervous, and for those who are just not quite sure what the right balance is, I think there's lots of us who can be allies to them,” Briggs says. “That is about helping people in a very straightforward, no-nonsense way, understanding what’s the business case for diversity? Why is it that you’re being asked to do this? What does good look like? What does bad look like?”

“It’s not just about doing the right thing. It’s about being the right kind of people, and building an industry that’s composed of all of the talent rather than just some of it, and then not being nervous about reaching out,” she adds. “This is where I think security membership organizations in particular have a really important role to play. Because they are the organizations who host our events, and who help us to understand what normal looks like and what good looks like, and what behavior is acceptable and not acceptable.”

How can organizations measure their DE&I efforts? Because, after all, what gets measured gets managed.

First of all, Briggs says that the industry needs much more data about who is part of security—demographics, the diverse communities represented (or not represented), and how those numbers have changed over time. Beyond demographics, the industry needs more data on progression and equity. Some CSOs surveyed by Briggs for the report are looking critically at promotions and pay raises through a diversity lens, checking that if men and women were scoring equally on management skills, then why were only men being promoted?

Briggs recommends “just being relentless in applying that lens to make sure that any unconscious bias, any inequalities don’t creep in as people are progressing through the department.”

In addition, many organizations collect belonging and inclusion indicators through staff satisfaction surveys. Those surveys can help security department leaders understand the sentiment among staff about DE&I, including “do I belong,” “does this place feel fair,” or “does my department tolerate jokes about gender and race?”

Briggs offers a few notes of caution about these metrics, however. The more homogenous your department, the more likely people are to say they feel included and that they belong—because they are surrounded by people just like them. “Just looking at inclusion and belonging indexes in the absence of absolute data on diversity can be confusing, actually, rather than clarifying,” she says.

In addition, when you start to dig into DE&I work, it raises the profile of the need for DE&I and changes employees’ expectations for their organization. This can lead belonging and inclusion scores to briefly decline as employees expect to see results from their leaders.

All of these efforts are well and good, but there’s still the elephant in the room when it comes to diversity in security: the talent pool. Many survey participants claimed that they wanted to improve diversity, but recruiters and HR professionals consistently looked to one pipeline for new security employees: the public sector, pulling from pools of former military, former law enforcement, or former intelligence teams.

“There are those who say, ‘Well, we would love more diversity, but the fact that we recruit from those un-diverse talent pools is holding us back. There’s not much we can do about it until the military diversifies or law enforcement diversifies,’” Briggs explains. “Actually, what was really interesting in the interviews with chief security officers that I did was I asked them very, very detailed questions about how valuable that professional background was. While they all valued what that could bring—and many of them came from it—they said it’s not critical. That background doesn’t add much to your ability to do this job.”

She notes that the findings don’t recommend turning away military and law enforcement recruits, “but rather that we can, with confidence, look from a wider talent pool to diversify our industry. That in doing so, we make it stronger and not weaker. This isn’t about compromising for the sake of diversity. It’s about getting a brilliant, brilliant group of talented people with different talents around the corporate security table to make our security efforts bigger, better, sharper, and more nuanced for the security challenges of today and tomorrow.”

Interested in learning more? The full report is available here (free for ASIS members).

Claire Meyer is managing editor of Security Management. Connect with her on LinkedIn or via email at [email protected].