Growing a Sense of Ownership with CPTED

Don’t underestimate the power of maintenance. When organizations are trying to bolster security at a site without undertaking large-scale construction project, simply maintaining the property to a high standard through landscaping, cleaning, or a fresh coat of paint can serve as a deterrent for crime.

“If you’ve ever been in a facility that’s not maintained, you can quickly equate that lack of maintenance to neglect,” says Mark Schreiber, CPP, principal consultant for Safeguards Consulting, Inc., and lead ASIS representative in the development of the new ISO standard 22341, Guidelines for crime prevention through environmental design. “Therefore, the potential criminal perpetrator can say ‘Oh, I might be able to perform my criminal acts here without being noticed.’ An area that is heavily maintained gives that level of accountability for the space, the level of activeness in the space, and therefore it is more difficult to do simple crimes because you’re more likely to be observed.”

The goal, Schreiber says, is to enhance the sense of ownership around the facility, which can be accomplished through smaller property improvements and by fostering stronger workplace culture.

Often, organizations are either moving into a leased facility to open a new branch office or they have purchased an existing structure as part of an expansion. This reduces security’s opportunity to make substantial infrastructure changes, from installing a widespread physical security system to building up perimeter security. But by applying Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles, security leaders can leverage natural elements and employee involvement to improve a facility’s security and customer service.

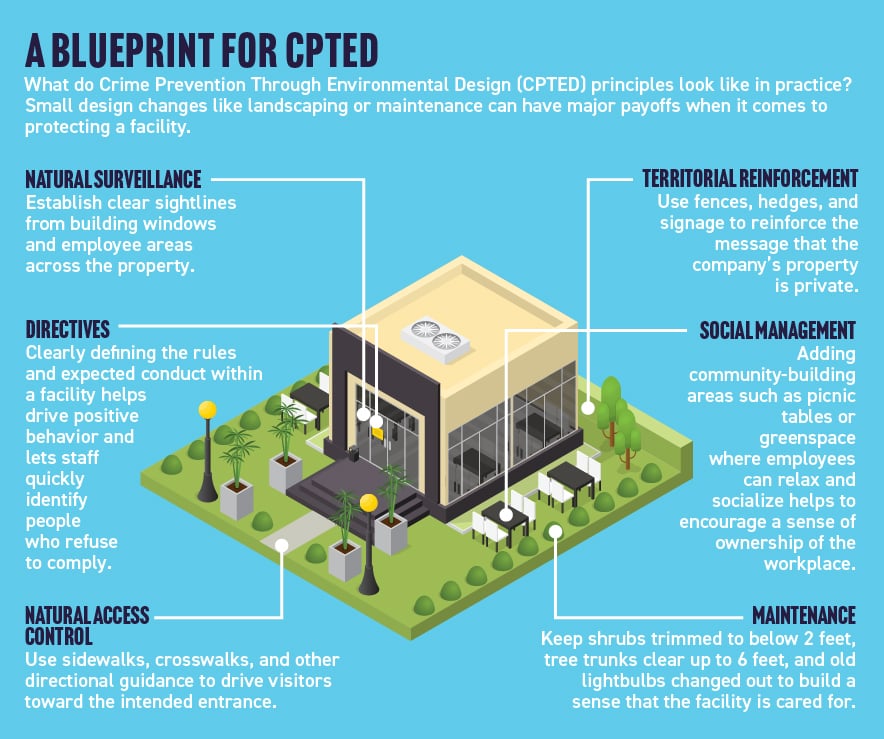

There are three primary categories within CPTED: physical design, social management, and directives, says Art Hushen, president of the National Institute of Crime Prevention, Inc. All three can be leveraged with relatively minimal cost for potentially huge payoffs.

Physical Design

The elements of physical design within CPTED follow one primary goal: influencing behavior. This includes the behavior of employees, visitors, customers, pedestrians, and potential ne’er-do-wells.

“There’s a lot of things we can do,” Hushen says. “Our job is to eliminate all the excuses for why people do not comply with the rules. ‘I didn’t know where to go.’ ‘There was no signage guiding me to check in to the front desk.’ ‘There was nothing that said I needed to hit this buzzer for access.’”

Vague design leads to visitors becoming frustrated, wandering around, and looking for alternative ways in, which could trigger a security response.

“To make the decision making easy as they transition toward your building and into your space, that’s one of the strategies that we’re really invoking when designating between public to semi-public and private space,” Hushen says.

Territorial reinforcement. One physical design goal within CPTED is to clearly delineate private from public property, and to make visitors pause and realize that they are entering an area with a different set of rules and guardians. This can cover a wide range of measures, including planting a hedge along the perimeter of a facility to ensure pedestrians realize that a grassy lawn on the other side is private property—not picnic space. For facilities with less green space, adding signage at entrances or painting the driveway or parking lot entrance a different color encourages visitors to take notice.

To Hushen’s point, a hedge or knee-high fence along a property edge eliminates trespassers’ excuses that they did not realize the property was private, and their obvious flouting of those boundaries can catch security’s attention.

Clear signage—including the company’s logo—around the property can also reinforce the notion that the area is private.

Natural access control. This concept follows a similar track to territorial reinforcement—if done well, it creates intuitive pathways for people to follow on the property while discouraging or restricting access to areas where they are unwelcome.

For example, Schreiber says shrubs and hedges can be used to keep people on sidewalks or designated pathways toward the front entrance of a facility.

Again, this enables security personnel to quickly sort out atypical behavior from the normal flow of traffic into and out of a building. If someone purposefully walks in a different direction than the route influenced by CPTED measures, it should be a warning sign to investigate further. The person might be lost or confused, or he or she might be looking for a different way into the building for nefarious purposes.

“Natural access control is the planning of the pathways, sidewalks, and driveways to get you to the front door,” Schreiber says. “In a well-designed facility, the front door will have a very wide, clear path from the visitor parking area straight to the door, and the employee areas are not as prominent. The front door is a celebrated entrance—big, bright, beautiful, special, and unique for the entrance.”

“In the case of an existing facility,” he adds, “it’s a case of taking what you have and beautifying it—magnifying it so that people clearly know that’s the door we should go to as a visitor, because it’s very prominent.”

Conversely, fences or thorny bushes can be used to keep people away from higher-security parts of the building where visitors should not wander. Hostile landscaping, including the use of thorny vegetation, can push people further away from areas such as large blank walls, which are tempting canvasses for graffiti artists. But Hushen cautions that security professionals should remember the purpose of the facility when considering implementing hostile measures. At a kindergarten or daycare, for example, shrubs with sharp thorns may not be an appropriate measure.

Instead, consider adding a wall of planters or other barriers, Schreiber recommends. Yes, someone could walk through that barrier, knocking branches aside and forcing his or her way through, but this is hard to do without attracting notice.

“That abnormal behavior should cause us to respond and investigate—ask for help, ask if you can assist them, and find out what made them go through that effort instead of following the more natural pathway,” Schreiber adds.

Natural surveillance. Can employees inside the building see across the property outside? Does the facility have windows, and are they unblocked by foliage or other obstructions? Are desks and lobby seats placed appropriately to give employees and receptionists clear views outside, so they can quickly detect and assess any questionable activity?

Hushen notes that natural surveillance—having clear views of anywhere unusual activity could occur and being able to report it promptly—is closely tied to both maintenance and to organizational culture. The overall goal is to improve lines of sight, while also providing a sense that an area is well-watched and that nefarious activity is unlikely to go undetected.

Landscaping plays an important role here, and Schreiber recommends following a two-foot, six-foot rule for foliage. Anything low to the ground, including shrubs and bushes, should be kept trimmed back and should grow no higher than two feet. Anything taller, such as trees, should have low-hanging branches trimmed to the six-foot mark. This leaves a solid four-foot gap, enabling people inside to clearly see through any ground-floor windows while eliminating places for people to hide in the foliage undetected.

These same principles can apply within a facility, including bank branches, says Omar Valdemar, CPP, senior vice president and manager of corporate security systems for City National Bank, based in Los Angeles, California. City National Bank often leases facilities within larger buildings for its branches, and that means security must adjust its measures to fit within an existing footprint. While the exterior of buildings is often hands-off, Valdemar and his team do have more leeway inside to influence client and visitor behavior.

City National first implemented controlled access at the entryway around a decade ago, and the measure has spread across many if its branches. The front door is locked, and customers must request entry into the branch. This gives colleagues an opportunity to acknowledge everyone who enters the branch while performing a speedy risk assessment. Bank employees rarely deny anyone entrance, but they can use the few seconds between a request for entry and the door opening to tell other employees to be alert. This clear line of sight to the front door enables employees to see suspicious activity outside and signal for help from inside, Valdemar says.

Employees’ desks and computer monitors are positioned so their colleagues can quickly see the customer at the front door and throughout the facility. Thin partitions are used around desks to give clients more privacy during consultations and banking services. Cash dispensing machines are tucked away in locations that are not easily accessible or obvious for non-employees, which provides a layer of security for the colleague.

One essential physical security element that plays a key role within CPTED is lighting, and Valdemar says he tries to build lighting requirements into branch leases—especially for facilities with outdoor ATMs.

“We want to make sure there’s enough light on the interior so that folks outside can see what’s happening on the inside, even at night,” Valdemar says. “Environmentally it might not be great to leave lights on, but we tend to try to leave lights on—especially around areas that might be higher risk, like a vault door or cash recyclers—so that if someone were to try to commit a burglary, someone from the outside could see what’s going on. We make it uncomfortable for a bad actor to burglarize our facilities or our assets.”

Valdemar uses what he calls the “Amanda assessment” to determine whether a site needs more security measures applied. When surveying a site, he asks himself if he would feel comfortable if his daughter, Amanda, were to use the ATM at midnight. If the answer is “no,” then additional steps likely need to be taken.

While some security measures are not possible within the terms of a lease or a particular location, they can often be tailored or a workaround developed.

“We just have to adapt to what we have and mitigate risk as much as possible,” Valdemar adds.

Usually building managers or the facility owner’s security subject matter expert are willing to compromise around security, especially when it does not require significant construction. For example, they are likely to agree not to put a large planter—which people could potentially hide behind—near an ATM or along the pathway between the cashpoint and a customer’s vehicle.

If possible, Valdemar adds, bank security teams try to influence the design of parking areas—vehicle pathways in particular—to change the angles of approach and reduce the risk, for example, of a person hitching a large truck to an ATM and then dragging the cashpoint away.

Social Management

Acknowledging each visitor as he or she enters serves more than one purpose within City National Bank. It eliminates the sense of anonymity for the visitor, while bolstering customer service and the workplace culture at the bank branch by fostering a sense that the employees share a goal of stronger security.

“We train our colleagues that by greeting individuals who enter, that customer service response will make that individual think twice about doing something wrong,” Valdemar says.

“Most folks are opportunists—that guy who can’t make rent who is thinking about cashing a fraudulent check or thinking of committing a robbery,” he adds. “They might drive around and case your branch, but when they walk in and you start with customer service, they see your eyeballs, and they hear that ‘good morning,’ they are going to think twice about doing a bad act in your facility. What they wanted was to come in in darkness, under the radar, get in and get out as ghosts so no one could see what happened. You are removing that opportunity.”

Internal policies like this create a state of ownership for employees—a part of the social fabric that supports workplace culture, Hushen says. Security teams can apply all the physical elements of CPTED but still fail to detect criminal activity if they have not successfully engaged the workforce. Employees who feel that they are responsible for their workspace are more likely to report suspicious activity and keep an eye out for their colleagues’ safety. In larger facilities that have other services such as childcare, employees are even more likely to make use of natural surveillance views to monitor the grounds or to notify maintenance when an outdoor light is malfunctioning, he adds.

“Social interaction creates that sense of ‘I like the place I work and the people I work with, and I’m going to take care of them,’” Hushen says. “It’s that people-centric approach that really makes a big difference, and that falls right into the CPTED component of social management.”

In healthcare organizations, Hushen says he has seen team-building days where employees from across floors and departments join in for food truck meals or games like gurney races. These social activities build social bonds across floors or departments, fostering a greater sense of awareness of colleagues and social cohesion so that if a nurse on one floor notices something amiss in another area of the building, he or she knows who to contact and wants to keep those colleagues safe.

“It’s all about that spirit of the workplace that we can really build on,” Hushen says.And he adds that blending customer service with workplace security and awareness can bolster social management while improving the reputation of the facility with customers and visitors.

Physical elements can also create a sense of community. Public art installations, for example, can endear a facility to a neighborhood, and people will be more likely to report suspicious activity around such a community landmark, Hushen says.

Inside the facility, companies can establish a sense of ownership by painting the lobby in company colors or using branded elements such as logos to clearly identify the space as part of the organization’s environment and culture.

Directives

The final element of the CPTED triad is directives—simply, the rules laid out by a facility that everyone must follow while on site. Clearly communicating these rules through signage at the perimeter or at the front door provides a way for legitimate visitors to acknowledge and obey the terms of use for the facility. Similarly, people choosing not to follow those directives are easily picked out of the crowd because they attract the notice of employees and security personnel.

For example, Hushen says, a visitor entering a facility might read the sign “Visitors must check in at desk” or “Face mask required for entrance” at the front door. This sets the standard of behavior up front and lets the visitor adjust accordingly. It develops a relationship of compliance and trust between the organization and the visitor right off the bat, letting front desk personnel quickly identify when a noncompliant visitor may need additional attention.

Beyond CPTED

The primary strategy in CPTED is “natural, natural, natural,” Hushen says. However, when those measures cannot extend any further, it’s time to turn to harder security measures such as video surveillance systems and access controls.

If a facility is short on exterior windows, it’s time to add a camera system. While this often means the organization loses some real-time viewing into exterior events, video fills in the gaps in natural surveillance, Hushen says. In addition, organizations can add motion-activated lighting to attract staff’s attention.

LED lights make this easier than ever, he notes, as organizations can dim parking lot lights to 25 percent power after dark, but then crank up the wattage when motion is detected. This can serve to light the way as employees return to their cars after dark, while also signaling that there has been recent motion in the parking lot—so employees should be alert.

Not only can the elements of CPTED—especially when used in concert with security hardening techniques and technology—save organizations money, but they broaden security professionals’ toolboxes to include elements of design that can help guide people, including colors, public art, landscaping, and principles of human behavior, all while influencing people’s perception of the organization, Hushen says.

“You need that security manager who’s able to blend the best of both worlds—CPTED and physical security. You put that together in one package and the assessments you can do are just amazing,” Hushen adds. “You blend good design, social management, and placemaking strategies, and then combine that with physical security—you pretty much cover every section of the building by thinking about safety and use of that facility.”

Claire Meyer is managing editor of Security Management. Connect with her on LinkedIn or email her at [email protected].