Crisis Intervention: A Stabilizing Force

Sometimes, ambiguity is a good thing. It allows people to be creative, surprising, and to make an impression. But when responding to a crisis, ambiguity is not a positive attribute. It pays to have as much information as possible beforehand to adequately prepare to respond.

Pietro D’Ingillo, Psy.D., learned this the hard way when he and his partner, another psychologist in California’s L.A. County, went out to respond to a person in crisis without backup.

“We came within feet of being faced with an incredibly disturbed individual who was on a four-day meth binge and holding a sawed-off shotgun,” D’Ingillo says. “We were interrupted by his mom, who said he was going to kill her, us, and everyone.”

D’Ingillo and his partner were able to get the woman in their car, drive away, and park where they could maintain visual contact with the home the man was inside of while they waited for police to respond. Six hours and a standoff later, the incident was over after the man attempted suicide with the shotgun.

“That was one of the experiences where there was room left for some ambiguity that may have prevented us from walking into that situation,” D’Ingillo adds.

D’Ingillo responded to many such situations during his time in Los Angeles, California, as a then community psychologist. These experiences made him and others realize that more needed to be done to prepare law enforcement and mental health practitioners to respond to people in crisis and to prevent crises from happening in the first place.

Across the United States, this has led to the rise of crisis intervention training programs—including in L.A. County where D’Ingillo, another psychologist, and two sheriff’s department sergeants now regularly train sheriff’s deputies on crisis intervention and stabilization.

“Now, training law enforcement, we act as the conduit. We act as the enzymes for deputies to further break down those symptoms that they see in the community and provide explanations for those behaviors,” D’Ingillo says. They can also act as a conduit for help, stabilizing a situation so a person in crisis can get the care he or she needs for long-term support—not just a night in a jail cell—as part of a broader crisis intervention program.

Memphis Beginnings

Everyone experiences crises. It can be the death of a loved one, a diagnosis of a serious illness, a divorce, psychological distress, a traumatic event, or other overwhelming situations. Some crises, however, are more challenging to navigate than others, and can be exacerbated by other factors such as mental illness or family stressors. Crisis intervention is a technique designed to reduce the potential permanent damage to an individual experiencing a crisis.

“A successful intervention involves obtaining background information on the patient, establishing a positive relationship, discussing the events, and providing emotional support,” wrote David Wang and Vikas Gupta for the National Center for Biotechnology Information, part of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

When a severe crisis is not addressed, a person can experience significant psychological stress—which can be linked to depressive disorders and other mental health conditions. Sometimes, unfortunately, this stress can result in incidents where law enforcement is called to respond.

In 1987 in Memphis, Tennessee, police officers responded to a call in a public housing area where a man with a history of mental illness was threatening people with a knife. The officers ordered the man to drop the weapon, eventually opening fire and killing him when he refused.

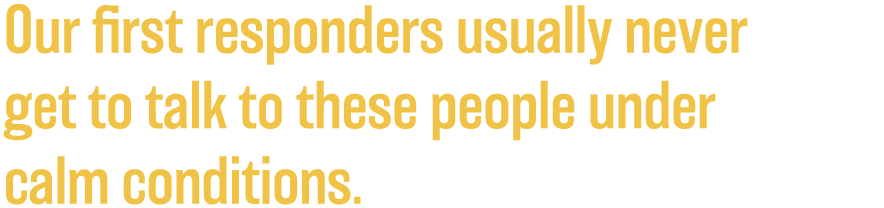

In the aftermath, community members called for a better response to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. The mayor worked with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the police department, community mental health professionals, and other leaders to create what became known as the “Memphis Model,” the Memphis Police Department Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) and the basis for many current crisis intervention training programs across the United States.

The Memphis Model takes the approach that instead of taking an individual in crisis to jail, police officers instead transport him or her to a mental health care facility. Police officers are also trained on basic crisis intervention and available community resources to aid individuals, such as community mental health services, social services, or veteran’s services.

After the model was implemented, Memphis saw a decrease in the number of individuals with mental illness entering the criminal justice system. It also saw an uptick in healthcare referrals.

The model was then formalized, and other communities began to express interest in adopting a similar approach to community engagement and crisis intervention, says Ron Bruno, executive director of Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) International.

Bruno’s community was one of them. After several incidents where law enforcement responded to an individual experiencing a mental health crisis that turned violent, his community decided to explore other options. Bruno was chosen to attend the Memphis Model training as a representative of his then-law enforcement agency and ultimately adapt it to his home community in Utah. He later went on to become the CIT program director for the U.S. state of Utah.

At its core, CIT is a community-level response involving law enforcement that seeks to prevent people from going into crisis in the first place, Bruno says.

“We’ve realized we don’t need police to go out to every call,” Bruno says, explaining that when people call 911 the dispatcher can assess if there is an actual identified level of danger that requires an armed officer or if a community service team, EMS, or a mental health practitioner would be a better response.

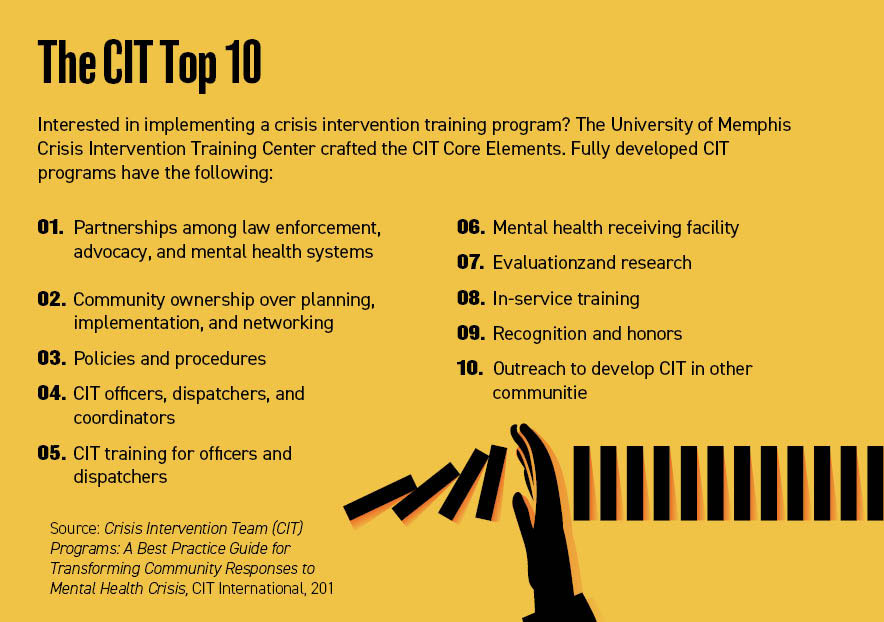

In 2019, CIT International published a best practice guide for CIT programs based on its analysis of more than 3,000 U.S. and international programs. It found four factors that create an environment for these programs to be successful, Bruno says.

First, the program needs a network of relationships between law enforcement, mental health professionals and advocates, and community members and leaders. It also needs an ongoing commitment from leaders, an understanding of the community-wide response to mental health crises, infrastructure to strengthen those responses, and a training program for law enforcement officers, 911 call-takers, and dispatchers.

“The first goal of CIT programs is to transform the crisis response system to minimize the number of times that law enforcement officers are the first responders to individuals in emotional distress,” said Don Kamin, director of the Institute for Police, Mental Health, and Community Collaboration, in the CIT International report. “If it’s a mental health crisis, there ought to be a mental health response. So, with the support of law enforcement, peer and family advocates, and other partners, service expansion is a natural outgrowth of CIT.”

Security Partners

Security staff are often the eyes and ears of an organization. They interact with staff, sensing the normal flow of the day and the typical behavior of employees, as well as visitors and the public. These connections mean that security officers can be key partners in crisis intervention and stabilization, says David Weiner, CEO and founder of Secure Measures—a security management consulting firm.

“If someone comes in and they’re being harassing in nature or they’re yelling or causing a scene for no reason—if you’re speaking politely and this person is escalating their own behavior, then there’s something amiss,” Weiner says.

Prior to starting Secure Measures, Weiner was a regional chief of police for the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs Police in Long Beach, California. In that role, he worked with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department Mental Evaluation Team, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Mental Evaluation Unit, and the Long Beach Police Department Mental Evaluation Team to address veteran issues like crisis intervention and suicide prevention.

Weiner built on those experiences to create the Veteran Mental Evaluation Unit and a Threat Management Unit to prevent violence in healthcare settings that cater to the veteran community.

A key aspect he focuses on is attempting to understand why someone is in crisis and that they might not be cognizant of needing to ask for help. Weiner, for instance, talks about the need to show empathy and compassion while allowing an individual to vent.

“For security practitioners, be patient. Just because you have other things going on doesn’t mean that they’re more important than what’s occurring,” Weiner says. “You can’t rush someone through a crisis because you’re on a schedule.”

He also emphasizes the need to understand what available resources security staff can refer individuals in crisis to—whether it be a fellow colleague or a visitor—and when it is necessary to call for back-up, whether that’s a mental health professional or a law enforcement response should an incident escalate.

For instance, a training exercise Weiner conducts involves showing students videos of incidents that escalated. One example was of a woman who enters a McDonald’s to place an order. When she receives it, it’s wrong, and she gets extremely upset and begins assaulting the staff.

“This lady was attempting to go behind the counter. There’s no point in engaging someone who is not listening to you in a physical altercation,” Weiner says. “Back up and let the manager handle it. Or call the police. There’s nothing in the store you’re selling worth dying for.”

And after an intervention occurs, Weiner emphasizes the need to ensure that the people impacted are given support. For example, providing time off for employees, connecting staff to mental health and counseling support—such as through an Employee Assistance Program—and making it clear that there are resources available to support employees to prevent the crisis from spiraling.

Training Diverse Responses

In the late 1990s, D’Ingillo trained as a law enforcement psychologist with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department. He also worked for a time in the L.A. County Jail and at the California Department of Corrections, the L.A. County Department of Mental Health, and the Los Angeles Police Department before returning to the sheriff’s department in 2016 as a psychologist with the department’s Psychologist Services Bureau.

In many of his roles, he was paired with a police officer to respond to patrol requests for a person experiencing a psychiatric crisis, and he started to see the value of having a mental health professional paired with a law enforcement officer.

“It will make the response more diversified,” D’Ingillo says. He cites the old saying “When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” meaning that law enforcement’s limited resources and training around response triggers them to treat all crises the same. Adding mental health practitioners and crisis intervention techniques diversifies officers’ toolbox so they can treat unique cases appropriately.

For instance, some situations the pair would respond to would involve someone who disliked police. D’Ingillo could approach the individual to assure them he was there as a psychologist to help—not punish.

On the flip side, some individuals would prefer to talk to a law enforcement officer instead of a psychologist.

“There’s something we created called the guardian effect,” D’Ingillo says. “Say, I’m highly paranoid and think someone is after me. I’m happy to be in the presence of a cop because whoever is following me will stop. I’m with a cop who has a gun and can keep me safe.”

Despite the work D’Ingillo was doing in responding to calls, however, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department did not have a formal CIT program. So, in 2015, the department decided to start one and put D’Ingillo, another psychologist, and two sergeants in charge of crafting the program and providing field training to patrol staff.

They created a 32-hour course called CIT 360, which is based on their experiences of responding to mental health crises in the field. The course is conducted during four days and is built around the concept of Respond, Observe, Assess, and React—the ROAR Response Model: A Roadmap to Crisis Stabilization.

“You’re responding, during which time you’re gathering information and you’re coordinating your call,” D’Ingillo explains. “Then when you arrive, you observe and scan. What are the stabilizing and destabilizing factors? Then you assess how critical the situation is. And then the last ‘R’ is ‘React.’ You slow it down, as possible, and speed it up, as necessary.”

To help build rapport and connect with deputies in the training, D’Ingillo and his colleagues start off in a classroom and will allow trainees to air their grievances—such as why the training is necessary or the perceived failures of healthcare providers to address the broader mental health crisis—so they can be proactively addressed.

“Organizationally, it’s worked as planned and allowed for some deflating of frustration and didn’t allow for interference later in the week,” D’Ingillo says. “As an instructor, I always have to worry if someone is trying to hijack my class.”

They also incorporate law enforcement officer mental health and well-being, including stress and illness related to their job, and resources that are available to them. A major discussion point on day two is suicide: general public suicide, suicide by cop, and law enforcement suicide. Suicide is one of the leading causes of death in the United States and a major public health concern, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. In 2019, more than 47,500 people died by suicide in the United States—more than two and a half times the number of people who died in homicides.

During the first six months of 2021, 155 law enforcement officers in the United States died in the line of duty (including exposure to COVID-19), according to the U.S. National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. As of Security Management’s press time, 120 law enforcement officers had died by suicide in 2021.

“Way too many cops kill themselves. You’re at greater risk of dying by your own hand than by a stranger in the street,” D’Ingillo says. He adds that in the training “we dispel myths, we explain confidentiality, and we give examples of deputies we’ve helped. That’s part of how we go about addressing wellness early on.”

On the third day of training, local NAMI representatives come in to share their experiences either of living with a mental illness or as a family member of someone living with severe mental illness.

“Our first responders usually never get to talk to these people under calm conditions,” D’Ingillo says. “Now they get to hear about the challenges and the emotional pain involved in being a family member or being the person living with mental illness.”

The last day of training is about community-related resources and how they can help deputies. The trainers review involuntary detention and how conservatorships work. They also discuss wellness practices that deputies themselves can engage in, especially on the job.

For instance, they review what a panic attack might feel like, how to practice meditation when relaxed, and how to calm themselves down if they are worked up during a stressful or traumatic incident.

The feedback from the community and department leads has been positive. In 2020, 98 percent of L.A. County Mental Evaluation Teams (MET) cases were diverted to mental health care facilities instead of jails, according to a January 2021 transparency report.

“Up to 34 lives were reportedly spared during potentially deadly force encounters involving consumers attempting ‘suicide by cop’ in 2020,” the report found. “These lives saved were credited not only to MET involvement but the higher level of preparedness for patrol deputies due to the vastly improved mental health training in recent years were also significant factors in these incidents.”

L.A. County has also created a fund to build a formal training facility to conduct ROAR training for the county’s Academy, Patrol and Sergeant School, and CIT 360. This ability to train deputies for their role in a broader CIT effort will be important because mental health crises are expected to increase in 2022.

“Since the outbreak of the [COVID-19] pandemic, MET units have seen a steady rise in case severity in addition to more crises being reported countywide,” the transparency report said, adding that calls increased from 2,148 during the 104 days before the initial stay-at-home orders to 2,372 after the stay-at-home order.

D’Ingillo also says feedback from the deputies themselves has been overwhelmingly positive. During the course—and afterwards—deputies have spoken to him and his colleagues about obtaining resources for parents and siblings who are homeless, and fellow deputies that they are concerned might be having suicidal thoughts.

“I had one deputy who said, ‘My father has serious anger issues. I have anger issues, and now I’m seeing it in my seven-year-old son. Can you help me?’” D’Ingillo says. “We’re part of the department that provides that kind of assistance.”

Megan Gates is senior editor at Security Management. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @mgngates.