Criminals Eye Stalled Supply Chains for Weak Links

Cargo theft was on the rise in 2019. The National Retail Federation’s Organized Retail Crime Report found that 73 percent of retailers surveyed in the United States suffered cargo thefts in 2019, compared with just 30 percent in 2018. According to the Cargo Theft Report 2020 from BSI and TT Club, 2019 saw an average of eight global cargo thefts per day, with 87 percent of attacks targeting trucks.

Then, in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Shipping and supply chains ground to a halt, and so did cargo theft and supply chain crime rates in the wake of national lockdown measures and stay-at-home orders. As countries lifted restrictions, however, industry experts warned that supply chain theft would soon return with a vengeance.

Then, in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Shipping and supply chains ground to a halt, and so did cargo theft and supply chain crime rates in the wake of national lockdown measures and stay-at-home orders. As countries lifted restrictions, however, industry experts warned that supply chain theft would soon return with a vengeance.

The Transported Asset Protection Association (TAPA) received more than 400 reports of thefts of products from supply chains in the Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) region from 1 March through 29 May 2020; altogether, losses were valued at more than €16.4 million ($19 million). Over the same 90-day period in 2019, TAPA’s incident database received more than 2,500 cargo theft notifications.

Despite these slower than usual rates of cargo theft in the first few months of the pandemic, TAPA warns that transportation organizations should expect a spike in crime as regions reopen and criminals seek to make up lost revenue.

The association is already seeing an uptick in attacks. TAPA EMEA recorded 118 cargo thefts in June, according to preliminary data, including nine major thefts with loss values of €100,000 ($117,000) or more.

COVID-19 uncovered a lack of preparedness along supply chains that criminals can exploit, says Thorsten Neumann, president and CEO of TAPA for the EMEA region.

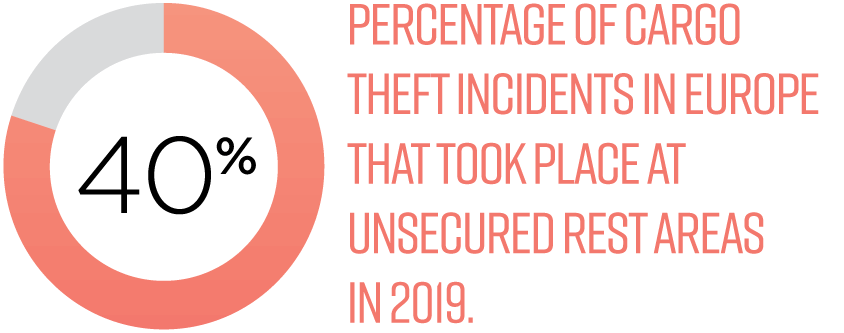

For example, in the Schengen Area of the European Union, where traffic can usually flow freely across 26 national borders to better facilitate trade and travel, pandemic lockdowns dramatically changed the status quo. Suddenly trucks full of goods were stuck at border crossings for hours, if they could cross at all. And those drivers who did get through had to make unplanned stops to rest, putting goods at risk at unsecured parking spaces and truck stops. Organizations were broadly unprepared for this level of sudden border closures, so plans for securing cargo during these stops were largely lacking.

In Europe, 40 percent of cargo theft took place in rest areas in 2019, and unsecured roadside parking accounted for 14 percent of thefts, according to Cargo Theft Report 2020. These extra stops and changes of plan put carefully developed risk mitigation strategies at risk, whether interruptions occurred in Europe, North America, or Asia.

In China, for example, ground transit across provinces is always a challenge, but COVID-19 made it downright impossible, says Kent Kedl, a partner at Control Risks, Greater China and North Asia. The overall difficulty is the sheer volume of supply chain activity in the region, and lockdowns associated with the pandemic revealed the extent to which global companies relied on supply chains through China.

“The mad rush to reduce costs over the years has resulted in a lower cost supply chain and a concentration of supply chains in places like China, but unfortunately the rush to reduce costs left redundancies behind,” Kedl says. “Companies could be forgiven, though, because I think in all our supply chain resilience plans, none of us had a plan for all of China going completely pear-shaped over a matter of weeks, and the rest of the world following after that.”

Rerouting product, whether through unfamiliar regions or unplanned stops, meant organizations’ speedily mitigating risk in new, unexpected environments. But criminals often adapt faster than organizations can, taking advantage of the confusion for organizational or personal profit.

Organized Crime

Cargo theft is a lucrative and low-risk revenue stream for organized crime groups, says Björn Hartong, CPP, practice leader for marine and security and principal risk engineer at Zurich Insurance Group.

When crimes are committed along multinational supply chains, investigations often stall—it’s difficult to determine where exactly the theft took place, and when the cargo crossed borders, a lack of cooperation between countries hampers inquiries even more, making the risk of capture relatively low for thieves, Hartong says.

Criminals are risk managers, too—if they exert energy, resources, and money toward a crime, risking imprisonment, it has to pay off, he adds. Cargo theft carries a low risk of prosecution. In most countries, thieves face little more than a theft or breaking and entering charge. Meanwhile, the potential profits are substantial. This is what makes cargo theft so attractive.

It’s not always the most expensive items that are targeted, either. As demand skyrocketed for typically low-value products like face masks, criminals began targeting them, too, he says.

For example, in April 2020, a Spanish businessman stole approximately 2 million face masks and various other protective equipment from a warehouse, selling most of them to contacts in Portugal. Hartong says that disposable protective equipment like masks and gloves would have been an unlikely target a year ago, but thieves adjust to meet demand and make profits.

Criminal organizations sometimes use cargo theft as a means to fund riskier, higher-profit ventures like drug trafficking. Organized crime groups also benefit from a less visible black market, Neumann says. Stolen product can now be easily sold for close to sticker price in online resale or auction stores, where the operation benefits from an air of legitimacy instead of making deals on the street for cut prices.

While theft is profitable to criminals, the victims face losses much higher than the cost of cargo. According to the Cargo Theft Report 2020, the median value of global losses in cargo theft incidents ranges from $100,000 in South America to $11,000 in parts of Asia.

But Hartong adds that “the fact that you lose the freight is not the overall cost. Research shows that actual cost of freight is about eight times as high; so if you lose $1 million in products, you’ve lost $8 million for the economy.” That compounding effect comes from the cost of recalls and testing, replacing the product, investigating the loss, lost sales or customer relationships, damaged vehicles, injured workers, and multiple other factors.

Organized criminal groups and drug cartels in Mexico have historically targeted freight trucks to steal the truck and use the machine to blow up roads or cause a crisis in a region, says Roberto Atilano, CPP, corporate security manager, Mexico and Central America, for confectionary manufacturer Ferrero.

“We’re facing the same risks that we were facing over the past two years,” Atilano says. “What we have been doing to minimize that risk to the company has not changed: we’re addressing education and avoiding risky routes. I see that more crimes right now are committed with excessive use of force; attacks on trucks are more aggressive right now.”

In specific risk areas across Mexico, particularly central and western Mexico, feuds between cartels and crime groups exacerbate transportation risks.

“As soon as there is a fight for territory control, the competition undercuts their core business, and they start to look around for alternative ways to make money,” Atilano says. “They see that one way to compensate for the lack of drug trafficking is cargo theft.”

Cargo theft is particularly challenging for food and beverage companies like Ferrero. According to a SensiGuard Cargo Theft Report, 40 percent of cargo theft incidents in Mexico in the first quarter of 2020 involved food and drink products. Cargo was most frequently stolen by hijacking (83 percent) and in-transit (82 percent), but cargo theft rates vary widely across regions. The SensiGuard report notes that 65 percent of cargo theft in Mexico occurs in the central region, and that violence in cargo theft is on the rise.

In Mexico, organizations also must deal with an increase in crime targeting ocean freight, not just landbound freight. Supply ships in the Gulf of Mexico have been targeted dozens of times in the past few years, triggering a security alert this June from the U.S. government.

“Armed criminal groups have been known to target and rob commercial vessels, oil platforms, and offshore supply vehicles,” according to the U.S. Department of State warning. Pirates robbed crew members of money, phones, and computers, and they stripped vessels and oil platforms of communication and navigation equipment, fuel, motors, oxygen tanks, and other high-value materials.

“In the first six months of this year, we’ve already had as many attacks as in the whole of 2019,” Atilano says. “We have to worry because the crews of ships have suffered attacks, and there were some people injured. It’s the same as in trucking—criminals are becoming more and more aggressive every time.”

Insiders

The ease with which criminal groups can gain information on supply chains or cargo contributes to this problem—approximately 70 percent of supply chain and cargo theft is associated with insider involvement, whether intentional or accidental, says Neumann.

Many blue-collar workers in logistics are short-term, low-paid workers, which makes them easy for criminals to compromise, Hartong says. They may be asked to share information on inventory, cargo routes, or shipment dates in exchange for quick cash. Additionally, criminal organizations have sent members to work in warehouses and in logistics posts, doubling their salary in exchange for useful information.

Many blue-collar workers in logistics are short-term, low-paid workers, which makes them easy for criminals to compromise, Hartong says. They may be asked to share information on inventory, cargo routes, or shipment dates in exchange for quick cash. Additionally, criminal organizations have sent members to work in warehouses and in logistics posts, doubling their salary in exchange for useful information.

“In the past, you had warehouses where people worked there for their entire life; people had a sort of trust and social values—they would not sell out the information they had from the company,” he says. “Now this new setup has a lot of flex workers; how committed are you to the company if you know they are only using you for a week, then afterwards you can go again, and you have no income? The same goes for truck drivers and anyone in the supply chain—they are not as socially committed anymore to the company they work for, and that’s something criminals can use.”

Neumann adds that “this inside information is making it easier for criminals to target a company, find its weakest links, and then attack at the minute when you are not prepared. But right now, the weakest links are popping up faster than you can control them.”

While insiders may be sharing information that leads to cargo loss, insiders are also potential threats themselves. In China, loss due to insiders was long considered a typical cost of doing business, says Kedl, although organized crime is significantly less common than in other parts of the world. Historically, self-enrichment schemes—overloading trucks with extra product, only some of which reaches the destination, or getting kickbacks for arranging transportation through a particular subcontractor—were systemic in fast-growing industries in the region, particularly food and beverage companies.

Most cargo loss in China is due to insiders, which makes it more difficult for companies to pay attention to, Kedl says. Stakeholders jump to attention at the phrase “organized crime,” he adds, but a misbehaving employee seems too commonplace to focus on.

In the economic boom of the 1990s and early 2000s, organizations rushed to hire vendors quickly and grow without many safety measures or much due diligence, Kedl says. Now that growth has slowed, organizations are focused on right-sizing their operations and supply chains, and they are taking a closer look at the partners, distributors, and vendors they hired during the boom.

“In the past, when everything was going so well and people were making a ton of money, the reaction we got so often was ‘it’s just the cost of doing business,’” he adds. “The supply chain inefficiency, the leakage, and stuff falling off the back of the truck—that’s just how business was done. And that’s how it was excused. We still hear that excuse now, but more and more, people are taking it seriously. They are realizing that there is a risk of financial damage—not just pennies on the dollar but real money that they’re missing—and reputational damage inside and out of the company.”

The reputational risk can be substantial, especially if there is a threat of counterfeiting, product tampering, or damage to sensitive products, such as pharmaceuticals. There is also an internal reputational risk to consider—Kedl cites multiple cases in which employees, when caught stealing or enabling theft, said that the company clearly didn’t care about monitoring its inventory, so what was the harm in making a profit for themselves?

Investigations into these issues often reveal that supposed mitigation measures are not working, he says, requiring a more forensic investigative approach that assumes the problem is systemic and seeks to root it out. But this is time consuming and often expensive, and Kedl says he assumed that most companies would not have the resources to focus on this during a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, especially as they hustled to get supply chains back up and running.

But because businesses were forced by stalled supply chains to slow down and reevaluate priorities, many turned a sharp eye on insider theft, using the pandemic as an opportunity to reset company culture and ethical expectations.

When discussing the magnitude of taking on a widespread investigation into insider threat and theft in 2020, one client told Kedl: “This recovery is going to be a marathon, and you can’t run a marathon on a broken leg. Right now, with our internal supply chain issues, we have a broken leg, and we have to solve this now.”

Opportunists

The rise in eCommerce shopping during COVID-19 has put significantly more pressure on last-mile deliveries, which have become a target for opportunistic package thieves and hijackers, driven largely by convenience and economic need.

Atilano says the pandemic has triggered a notable rise in attacks on secondary distribution and last-mile transportation—particularly small trucks delivering product to convenience stores or pharmacies. Opportunists have applied various methods, including hijacking, slashing truck tires, or simple breaking and entering, to attack delivery trucks and get smaller portions of product.

While some of this crime occurred before COVID-19, the pandemic and its ensuing economic instability have exacerbated this type of cargo theft.

“Because of the pandemic, a lot of people lost their jobs, they are hungry, and they need to provide, somehow, to put food on the table,” Atilano says. “They’re looking for different situations,” including petty theft, to generate small amounts of revenue.

Risk across regions relies largely on the country’s economic situation and product demand, Hartong explains. Mobile phones may be an attractive target everywhere, but in developing countries, items like cement or food could be at higher risk. “It is all about the willingness of people to commit crimes and the market to sell product,” he adds.

For example, in the United States, people would likely not rob a truck delivering orange juice—it is not in high enough demand to justify a high enough price for the thief to profit. In a country with limited food supplies or economic hardship, however, that risk could be worthwhile—the few dollars earned by selling stolen juice could be enough to live off of for weeks.

For example, in the United States, people would likely not rob a truck delivering orange juice—it is not in high enough demand to justify a high enough price for the thief to profit. In a country with limited food supplies or economic hardship, however, that risk could be worthwhile—the few dollars earned by selling stolen juice could be enough to live off of for weeks.

The economic downturn associated with COVID-19 continues to influence this equation, Hartong says.

Neumann adds, “When you look at some of the most heavily impacted countries in Europe, we already see an uptick in criminal activity in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and other areas. The economy is slowly going up again, but that means that criminals are also targeting us again and more frequently, especially as you see more trucks on the road and last-mile deliveries on the road.”

Mitigation

By June 2020, the Mexican government’s statistics noted 22 percent less transportation theft than in 2019, with transportation volume plummeting between 25 and 30 percent, Atilano says. Fewer trucks on the road meant less opportunity for crime, but the reopening of businesses and movement of goods late in the second quarter of 2020 saw a corresponding increase in the amount of cargo theft.

In response, Atilano is reinforcing transportation safety measures and risk mitigation strategies, including reducing night shifts—especially in regions with frequent reports of hijacking—avoiding high-risk areas as much as possible; employing more armed escorts for trucks; using GPS and other technology to monitor drivers’ locations; and frequently changing routes and schedules to avoid establishing predictable routines.

“It is working so far; we see more benefits and less impact to our operations,” he adds.

Agility proved essential for retailers during the initial transportation shakeups, Neumann says. Those companies that could pivot to different facilities, reroute shipments, and adjust delivery schedules were

able to resume operations more quickly and securely, compared to manufacturers and older organizations that relied on longstanding, largely static supply chains.

Additionally, intelligence gathering and increased transparency with other transportation companies about risks, incidents, and trends is proving valuable for the industry, he says, as well as for individual organizations looking to bolster decision-making processes.

A lot of elements were never thought out in supply chain risk assessments, says Hartong, but many companies are now reviewing these plans, evaluating whether to store or manufacture product in higher risk regions, how many redundancies to build in, and what to do if a shipment is stalled or goes awry.

“A lot of companies have woken up now because of supply chain interruptions, and they are rethinking their whole strategy,” he adds.

Kedl encourages companies to use the COVID-19 experience as a catalyst to take an honest look at supply chains and rethink the status quo. Resilience, he predicts, will be a key performance indicator for many organizations evaluating supply chain plans in the years to come.

It may behoove organizations to start war gaming another COVID-19 outbreak along their supply chains, Kedl adds. Supply chain managers can look at what local and national government actions came down previously and strategize how to react to similar outbreak responses moving forward.

For example, cargo transportation in China shifted from road to rail as much as possible during lockdowns to avoid getting stuck in checkpoints or quarantine zones for weeks. Does the organization have appropriate plans and agreements in place for a similar shift in the future?

“COVID-19 exposed problems that organizations already had,” Keld says. “It’s like that phrase: When the tide goes out, you see who’s wearing a bathing suit. The tide went out, and people found they were exposed. When things slow down and you have a little more time on your hands, you start to pay more attention.”

A Change in Plans

From consumer goods to medication to medical devices, Johnson & Johnson has millions of dollars’ worth of products on the road at any given time. However, the COVID-19 pandemic put its security plans to the test.

The volume of products shipped daily by Johnson & Johnson, which operates in 187 countries, means a relatively high risk exposure, especially for consumer goods, which travel mainly by road freight. However, internal standards and good practices form the backbone of an adaptable, responsive security program at the company, says Carlos Velez, global security director for Johnson & Johnson.

“The program identifies risks along the supply chain and adopts prudent, preventative security and business practices to address those risks,” he says.

Johnson & Johnson’s robust supply chain security plans consist of approximately 36 layers of security initiatives. For example, suppliers are audited by a third party before joining the Johnson & Johnson supply chain, and security programs and requirements are included in suppliers’ contractual agreements. While there is some variation from country to country—regarding background check standards, for example—the structure of the program remains the same, addressing people, technology, and procedures, Velez says.

“The pandemic will create more security-related issues. More people are losing their jobs, and those social conditions in different countries are creating more risk to the supply chain. Cargo theft numbers initially decreased because everybody was in quarantine, including criminals, but as countries are lifting those restrictions, we expect that cargo theft numbers might begin ticking up,” he adds.

Responding to the rapidly evolving risks in 2020—from the pandemic to civil unrest and mass protests to cargo theft trends—requires an intelligence-driven approach. “Intelligence is a key component of those layers of security,” Velez says. “The fact that we can predict what’s going to happen—because there is a border closure, or there’s going to be a strike, or because there will be a road block somewhere for a Yellow Vest protest in Europe—that proactive information will give us enough to adjust operations and mitigate those risks.”

For example, the sudden reduction in airline services in early 2020 because of COVID-19 meant products that would usually be transported by air freight had to be moved by road instead, which heightened risks. While air freight usually faces some cargo theft risk, especially in the miles between the airport and its destination, the change in plans required alternative risk mitigation strategies and plans.

Companies must also be able to trust and rely on their partners, he adds. Having reputable suppliers that can take products from point A to B safely, intact, and in a timely manner has been essential, especially during a turbulent time like the COVID-19 pandemic. But partners are not just suppliers—drivers move millions of dollars’ worth of shipments every day, often at a $20 per hour pay scale. Hiring and retaining the right, trustworthy drivers and employees helps to keep products safe from tampering, theft, and loss, Velez adds.

Companies must also be able to trust and rely on their partners, he adds. Having reputable suppliers that can take products from point A to B safely, intact, and in a timely manner has been essential, especially during a turbulent time like the COVID-19 pandemic. But partners are not just suppliers—drivers move millions of dollars’ worth of shipments every day, often at a $20 per hour pay scale. Hiring and retaining the right, trustworthy drivers and employees helps to keep products safe from tampering, theft, and loss, Velez adds.

Johnson & Johnson is also using trace and track technology as a key component of its supply chain security. Through this program, the organization can track shipments in transit and confirm delivery in real time. In addition, the system can be used to identify a product by its SKU number, which enables investigators to identify stolen products on the market.

GPS technology is common in the supply chain security industry, Velez says, but criminals are getting very clever in their use of jamming devices and other measures to circumvent loss prevention tools.

“This is an evolving program; we need to be always on the front edge to ensure that we have the latest and greatest technology to protect our shipments,” Velez says.

“We are a company that is in the business of taking care of people’s lives,” he adds. “Our core responsibility is to ensure that we not only make outstanding products but that we deliver those in a timely manner to people who need them. We’ve got to be flexible, we’ve got to be agile, we’ve got to be more able to predict what’s happening. The lesson learned is: we’ve always got to have a plan B.”

Claire Meyer is managing editor of Security Management. Connect with her on LinkedIn or email her at [email protected].