Storms Continue to Pummel California, Any Drought Relief May Be Short-Lived

As major storms continue to pummel California, the United States may soon up its tally of weather and climate disasters to reach or exceed $1 billion in damages to 342.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has been tracking weather and climate disasters, and their subsequent damage, since 1980. At the end of 2022, the United States had recorded 341 incidents where damages and costs hit or surpassed the $1 billion mark, according to NOAA's annual report, Assessing the U.S. Climate in 2022.

Adding to that roster in the new year could be the ongoing situation in California. For two weeks, the U.S. state has endured one so-called “atmospheric river” after another. There is no end in sight to these deluges, and the severe storms are fast approaching the $1 billion mark in damage. The storms are also deadly; so far, 17 deaths have been attributed to them.

“It’s likely that this is going to be at least several billion dollars,” Jonathan Porter, chief meteorologist at AccuWeather, told The New York Times. “It will unfortunately join the club of billion-dollar disasters.”

The rain these storms are dropping can be measured in feet instead of inches: as much as 2.5 feet of rain have hit some areas in the last 17 days a National Weather Service meteorologist told Reuters. The snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains can be measured in yards, as in 1.3 yards this past weekend alone.

Floods are damaging homes, sinkholes and mudslides are also destroying property and wreaking havoc on transportation, and high winds are knocking out power lines. During the weekend, more than 300,000 people were without power, though by this morning that number had been cut to 50,000. The snowpack in the Sierra Nevada range is 215 percent of average for this date, leading to fears of avalanches that could cause further destruction.

The central and northern parts of the state have taken the brunt of the storms so far, but Los Angeles in the south experienced major disruptions from the atmospheric river that hit in the first part of this week. The sinkhole that swallowed two cars (see the photo at the top of this article) occurred yesterday in an L.A. suburb. Two people had to be rescued. Many communities in the area were under evacuation orders, though those have been lifted now.

“But just about every community in California has been jolted by the storms in one way or another,” The New York Times reported. “Extra snow fell in the Sierra Nevada last week. Heavy winds toppled power lines in Sacramento this weekend. Mudslides mucked up Los Angeles on Tuesday. Public transportation systems in major cities have been snarled, and roads have been temporarily shuttered just about everywhere, from the mountains to the valleys to the coast. In Malibu, a large boulder blocked a canyon road. In Fresno, a hillside crumbled onto a highway. And multiple stretches of the well-traveled Route 101 were turned into rivers.”

The next river is coming today. It is forecasted to miss southern California, focusing its deluge on northern California and flowing northward into Oregon and Washington. The storms will bring several inches of rain to those areas during Wednesday and Thursday. More storms are forecast for the southern part of the state beginning Friday into Saturday. As of press time, there is no indication that the weather pattern causing the repeated atmospheric river storms is changing, so the storms will keep coming.

An infamous set of storms, almost certainly atmospheric rivers like the state is dealing with today, deluged California for 43 days in 1861. That event caused the state’s central valley to become “an inland sea 300 miles long and 20 miles wide. Thousands of people died, and one quarter of the state’s estimated 800,000 cattle drowned,” according to the Scientific American. The bustling town of Sacramento, California, with a population of around 14,000 at the time, was under 10 feet of water.

One 2023 estimate said the state would receive 22 trillion gallons of rain during these storms. That’s about the same volume of water that flows over Niagara Falls in one year.

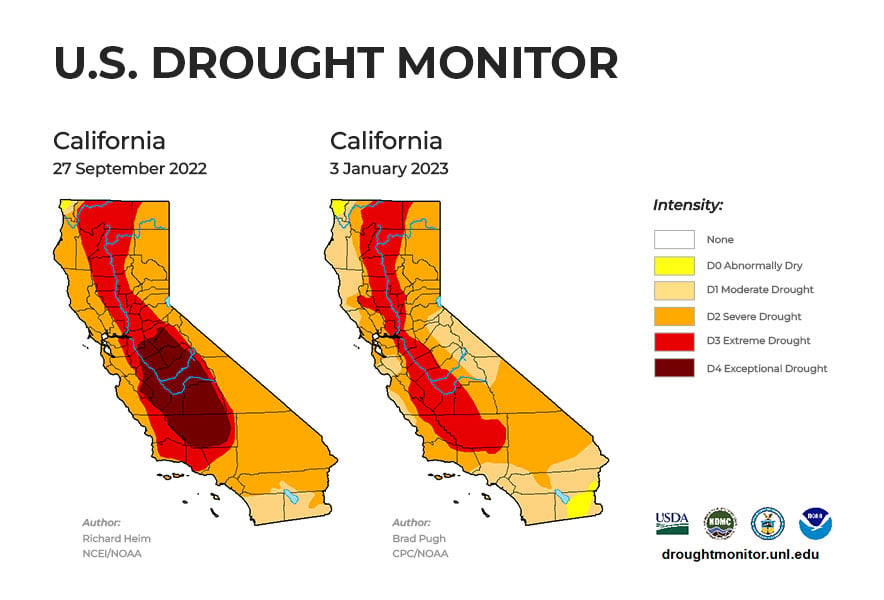

All of this water is bound to have an impact on the long drought affecting the state, a drought that researchers said is the region’s worst in at least 1,200 years. A Washington Post article took aim at how the water boom and bust cycle affects California, and how the state plans for it.

“Water scarcity in California, for good reason, has been all-consuming,” said hydrologist Jeffrey Mount, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California and professor emeritus at the University of California at Davis, in an interview with the Post. “But you can’t take your eyes off the wet periods [and] how to prevent catastrophic flooding. …That’s the big-time challenge.”

While the drought was getting the attention, many water resource experts were pleading for more attentiveness and planning for the potential affects of flooding. Deirdre Des Jardins, a researcher who launched California Water Research, told the Post that climate change increased the likelihood of a catastrophic megaflood event by more than 400 percent.

The state’s Department of Water Resources has taken steps to plan for an event like what is happening now.

The Post reported that “the department has taken part in tabletop exercises, known as ARkStorm, where state and federal agencies simulated their response to a 1-in-1000-year atmospheric river event. The agency is working with farmers to promote groundwater recharge projects and with reservoir managers to incorporate more sophisticated weather forecasting into their operations. …An increase in catastrophic storms ‘has been in the wings, predicted for a while,” said Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth. “But there’s nothing like being in it to start to shake off the old ways of doing business.”

Damage and destruction aside, the storms will have at least a short-range positive impact on the catastrophic drought. Comparing the beginning of the water year—which starts in October—through just the first week of storms shows how the storms have begun to mitigate the drought.

Reservoirs that were at half their traditional capacity or less have begun to fill. A small reservoir in Sonoma County rose from 50 percent of its average capacity to 80 percent, and will fill more with the continued storms. Even as the rain keeps falling, however, experts warn that the drought is far from over.

Snowpack is more than 100 percent of average throughout much of the Rockies, and is more than 200 percent in some places. But the director of the Colorado Water Center at Colorado State University, John Tracy, told online news site Grid that he remains pessimistic.

“We probably need to have a series of years where the average headwaters snowpack is well north of 125 percent, probably closer to 150 percent of normal,” Tracey said, adding that to bring water levels at the country’s two largest reservoirs—Lake Mead and Lake Powell—up toward capacity. “I have seen multiple years where we’re above normal, that can happen. But something like that happening, say, 15 years in a row? I would not put my money on it.”

As you consider how climate change affects security specifically, be sure to read this three-part series from Security Management that examines the implications of a hypothetical emergency created when a heat dome settles over an area that could be particularly vulnerable to such a meteorological event.

And more climate change preparation articles can be found on this list of the "11 Resilience Stories SM Editors Recommend" in 2022.