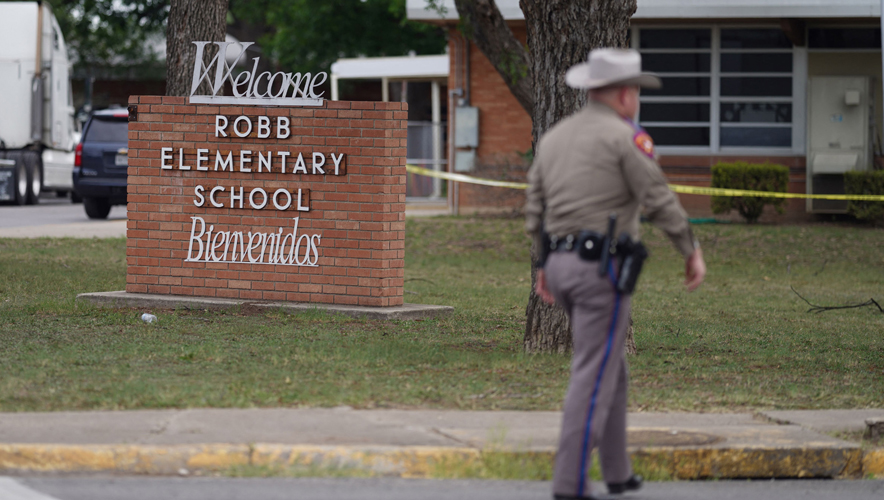

Texas Senate Hearing Clarifies Timeline of Uvalde Shooting

Details continue to emerge about the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, that left 19 children, two teachers, and the gunman dead on 24 May. In a painful, minute-by-minute breakdown at a Texas Senate committee hearing, Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw called the police response to the shooting an “abject failure,” explaining how police officers entered the school within minutes of the shooting but waited more than an hour to enter the classroom where the gunman was located.

McCraw’s testimony corrects some parts of the timeline of the shooting, The Washington Post reported. He told senators that the details of his account were drawn from video footage, including school surveillance cameras and police body-worn cameras.

According to McCraw, police officers armed with rifles were inside the school just three minutes after the gunman entered a classroom. Within 19 minutes, police had a protective ballistic shield. Shortly after, a student inside the classroom called 911. More ballistic shields were brought in as gunfire was heard from inside the classroom. A Halligan bar—an ax-like forced-entry tool that firefighters use to break down locked doors—was available, but authorities did not use it. Instead, police waited for a master key to arrive so they could open the classroom door, even though they had not established that the door was locked, according to the Texas Tribune.

The classroom doors could be locked only from the outside, though. “There’s no way to lock the door from the inside,” McCraw said. “And there’s no way for the subject to lock the door from the inside.” A teacher had requested the locks be fixed—believing they were broken—before the shooting, he added.

One hour and 14 minutes after the gunman entered the classroom, law enforcement officers entered the room and killed the assailant. McCraw said the delay was “antithetical” to common school shooter response training that was established in many police departments after the Columbine High School massacre in 1999—especially if children’s lives are in danger, police should confront and stop attackers as soon as possible.

Earlier this month, Uvalde CISD police Chief Pete Arredondo gave the Tribune his account of law enforcement’s response to the mass shooting.

— Texas Tribune (@TexasTribune) June 21, 2022

Now, new information from other law enforcement sources is conflicting with that account.https://t.co/mDLuxNoyzF

McCraw praised teachers and staff at the school for quickly initiating active shooter protocols when the attack began. He placed the blame for the delayed response squarely on the school district’s police chief, Pedro “Pete” Arredondo, who McCraw said was the commander on the scene and made the “wrong decision” not to pursue the gunman—viewing him as a barricaded subject, not an active assailant.

“The only thing stopping a hallway of dedicated officers from entering room 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander, who decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children,” McCraw said. “The officers had weapons, the children had none. The officers had body armor, the children had none. The officers had training, the subject had none.”

In an interview with the Texas Tribune, Arredondo said he did not consider himself the scene’s commander.

Due to conflicting narratives and a shift to closed door briefings with investigators and legislators, some analysts speculate if we will ever know the full truth of what happened in Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas.

Despite the lack of clarity, school districts across the United States face significant demand to ramp up security systems and protections to console panicked parents and concerned communities. School security experts are worried that this knee-jerk reaction could see schools spending significant funding on systems or services they do not really need, at the expense of more holistic, value-adding solutions.

Guy Grace, vice chair of the Partner Alliance for Safer Schools (PASS) and former security director for Littleton Public Schools in Littleton, Colorado, recommends that school security leaders slow down and do a full risk assessment before making any investments because of the shooting in Uvalde. Many school districts have not conducted a full, third-party risk assessment in years, he says, and therefore it’s hard to know what solutions will deliver legitimate value for the school beyond focusing solely on the high-impact, low-likelihood event of an active assailant.

“Assess before you treat,” advises Guy Bliesner, school safety and security analyst for the U.S. state of Idaho’s Office of the State Board of Education. This means assessing facilities, operations, processes, and compliance with the stated procedures. “We’re being buried with people trying to sell us stuff right now,” but many solutions being pushed at school security leaders are unlikely to solve the specific problems that exacerbated the security risk in Uvalde.

School security professionals must translate guidance and actions between law enforcement, teachers, and administrators to get traction. We spoke to the founder of Idaho's Office of School Safety and Security on the best ways to do this. https://t.co/FkisvE5wKA

— Security Management (@SecMgmtMag) May 27, 2022

If a school district has not evaluated its security infrastructure in several years—including what technology works, what is failing, what systems do or do not talk to each other—then it could have multiple gaps in its security posture without knowing it, Grace says. By investing in a more holistic, open architecture security system, school districts have more options to integrate systems and build in redundancies, so if one component fails, others can provide layers of security to serve as a backup.

In addition, the threat landscape evolves constantly, Grace notes. The way students communicate is always evolving, from one social media or messaging platform to another, from one trend to another, and keeping abreast of these developments is essential for useful threat assessments—especially when looking for signs of leakage that could signal a pathway to violence.

An effective security and risk assessment should examine all of these systems, processes, and protocols to determine where gaps and weaknesses might be to help schools spend their grants and funding wisely so that any investment can be used for both active assailant response and everyday issues like crime prevention or facilities monitoring, he adds.

Regarding the information coming out of Uvalde, Grace adds that “There’s so much grey in this situation right now—do we know whether the classroom doors were locked or could be locked? Do we know why that perimeter door didn’t latch?” Many people will “point fingers at law enforcement,” he says, but any after-incident review should also examine what protocols staff and students were taught about active shooter response and whether it worked or could be improved.

Bliesner notes that an effective after-action report needs to be an “autopsy without blame.” Investigators should look for system failures—whether those were choices to ignore or circumvent training and procedures or mechanical failures at the school perimeter—because those can be fixed.

“Individuals will make mistakes, but it’s systems we can fix,” he says.

Regarding Uvalde, however, Bliesner says that security professionals will need more distance from the event to gather accurate and actionable lessons learned. Neutral after-action reports can take months to generate, and even though school security leaders are under “screaming pressure to make changes” to reassure stakeholders that children will be safe, it behooves them to take a deep breath and slow down any decisions.

“It’s really unfortunate what happened down there,” Grace says. “All I can say is we don’t know all of the facts. It’s not just technology we need to re-look at here, but it’s the whole, big approach of unified security. We need to holistically look as a nation at what our mental health is going to be, how we’re going to unify that with the technology and equipment we put in the schools, how are we going to unify the threat assessment process, how are we going to unify the emergency preparedness processes, and how are we going to unify people’s roles? It’s just this gigantic picture that we have to be ready for.”

For security professionals looking for tools, resources, and guidelines to help inform school security assessments, training, or improvements, PASS offers a number of free guidelines and assistance. Visit here for more information. ASIS members can also engage with the School Safety and Security Community via ASIS Connects.