Book Review: The Liberation of Marguerite Harrison: America’s First Female Foreign Intelligence Agent

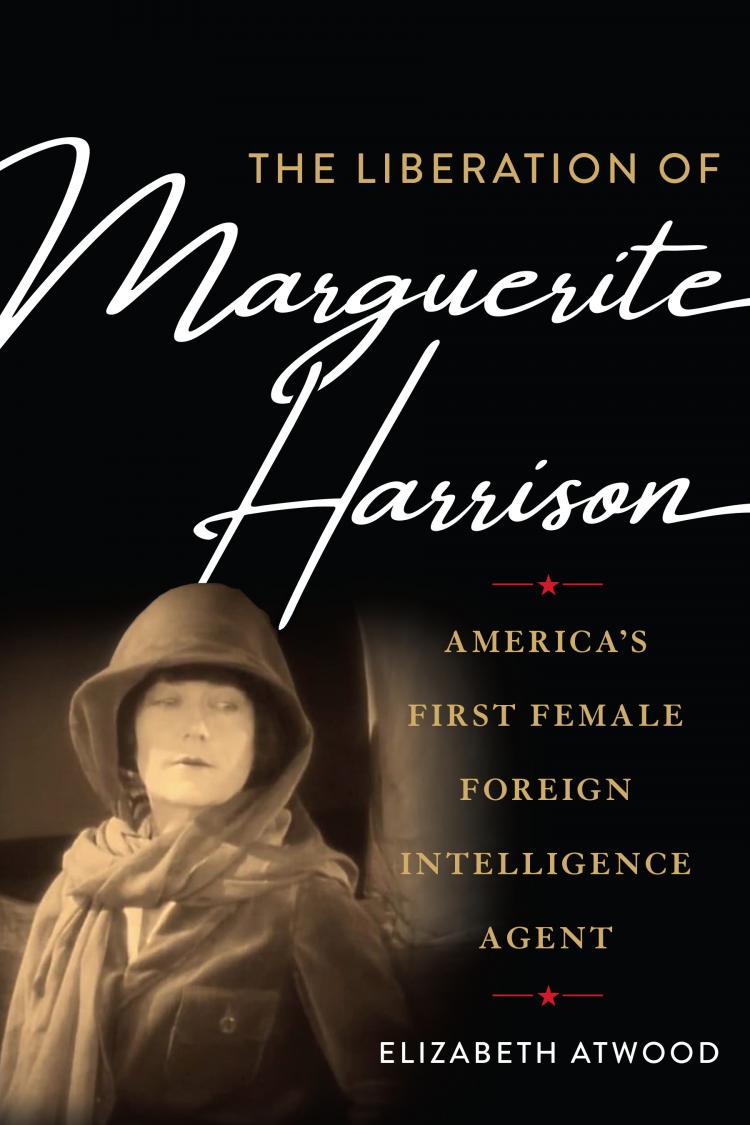

The Liberation of Marguerite Harrison: America’s First Female Foreign Intelligence Agent. By Elizabeth Atwood. Naval Institute Press; usni.org; 320 pages $32.95.

A good spy story filled with impossibilities, Elizabeth Atwood’s biography of Marguerite Harrison, The Liberation of Marguerite Harrison: America’s First Female Foreign Intelligence Agent, unpacks Harrison’s life and accomplishments. The author conducted meticulous research, using materials from the U.S. National Archives. This was no small task, given that Harrison’s life is a muddle of contradictions stemming from lost records and conflicting stories of her adventures.

A good spy story filled with impossibilities, Elizabeth Atwood’s biography of Marguerite Harrison, The Liberation of Marguerite Harrison: America’s First Female Foreign Intelligence Agent, unpacks Harrison’s life and accomplishments. The author conducted meticulous research, using materials from the U.S. National Archives. This was no small task, given that Harrison’s life is a muddle of contradictions stemming from lost records and conflicting stories of her adventures.

To determine the truth of who Harrison was, Atwood explores Harrison’s early life. She grew up as a debutante spending time in Europe as a child and later became a socialite in early 1900s Baltimore. Following her husband’s death, she became a society columnist and (ultimately) a reporter for the Baltimore Sun. This combination of experiences led Harrison to volunteer as the first female foreign intelligence officer in post-World War I Europe.

Harrison’s experiences in Moscow form the heart of the book—it recounts an initial assignment in 1920–1921 and includes her interactions with Solomon Mogilevsky, head of Cheka foreign intelligence service, and her eventual nine-month imprisonment in Lubyanka. The recounting of Harrison’s first assignment provides a window into economics and politics of early Communism, valuable to anyone seeking a greater understanding of the beginning of the Soviet Union. It also provides personal intrigue, as Mogilevsky attempts to recruit Harrison as a double agent.

Harrison herself appears sympathetic to Communism at times, adding another layer of complexity in assessing her value as a United States intelligence officer. The reader is left wondering—not because of Atwood’s research, but because of Harrison’s conduct and statements—where her loyalties truly were. This is complicated by a second, potentially unsanctioned, mission to Russia and second imprisonment, as well as later travels through the Middle East with famous filmmaker Merian Cooper. Atwood’s observations on Harrison’s time in then-Persia offer, as with the Soviet Union, a snapshot of Middle Eastern culture and developing political conflicts.

Written for a general audience, Atwood’s biography carefully navigates the fact and fiction of Harrison’s life, capturing what may have driven Harrison to set sail and serve her country through espionage. At the same time, Atwood does not shy away from Harrison’s personal weaknesses while detailing her contributions to early U.S. intelligence operations. What makes this biography compelling is Harrison herself. As Atwood states “…by many measures, Marguerite Harrison was a failure, both personally and professionally.”

At the same time, Harrison was a trailblazer for all women who ultimately aspired to careers in foreign intelligence, despite her own motivations. Of likely interest to all lovers of history and biography, Elizabeth Atwood’s The Liberation of Marguerite Harrison: America’s First Female Foreign Intelligence Agent reminds the reader of the imperfection of those who go first—not to devalue their contributions, but to place them in the appropriate context. Atwood’s research makes this book worthwhile; Harrison’s life makes it a spy story for the ages.

Reviewer: Laura J. Itle, PhD is an ASIS member and a researcher at a federally funded research and development center, where she has worked for 15 years on subjects related to national security, security planning, emergency management, and technology development.