Securing the Lost City of Machu Picchu

At 2,430 meters above sea level in the middle of a tropical mountain forest, Machu Picchu stands in an extraordinarily beautiful setting. It was—and may remain to be—the most amazing urban creation of the Inca Empire at its height, with its giant walls, terraces, and ramps seeming to cut naturally in the continuous rock escarpments.

The natural setting, on the eastern slopes of the Andes Mountains, encompasses the upper Amazon River basin with its rich diversity of flora and fauna. Located in the Urubamba River Valley, it rests on a rock formation that serves as a link between the Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu mountains.

Machu Picchu’s advanced architecture style—constructed on architectural terraces—is considered one of the most advanced of its time due to its polished stone methods and how it was transferred to the site; the Incas were famous for their walls of dry stone—huge blocks of limestone arranged to form buildings based on astronomical alignments to provide panoramic views.

In 1983, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared Machu Picchu a World Heritage Site—dubbing it the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu. Twenty-four years later, millions of people around the world cast votes to name Machu Picchu one of the seven wonders of the modern world.

Due to these designations, its unique beauty, and history, thousands of people pass through the small city of Aguas Calientes, Peru, at the foot of the mountain and hike or take the train to Machu Picchu every day. And while they are mostly there to admire and appreciate the UNESCO site, they also pose a security risk.

Threats to the Sanctuary

Machu Picchu faces a variety of threats: excessive tourism, which is especially hard on the fragile site; the generation of solid waste; unsustainable agriculture practices; overgrazing and forest fires; aggravating erosion; landslides; mineral extraction; and the introduction of exotic plants.

In September 1997, a large brush fire threatened Machu Picchu—causing firefighters to pump water on the vegetation surrounding the site to prevent it from reaching the ruins. The fire, which may have been started by local farmers to clear farmland, was ultimately brought under control when major rains swept through the area, but only after more than 800 hectares of mountain forests were burned, according to UNESCO.

Another example of the threats Machu Picchu faces occurred in January 2020 when four men and two women from Argentina, Chile, Brazil, and France were caught sneaking onto the site illegally and damaging a stone wall in the Temple of the Sun. One of the individuals allegedly defecated inside the Incan city. Peruvian authorities deported five of the tourists and arrested one of them on charges of vandalism, according to an announcement by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture.

Additionally, officials do not fully understand the impact an environmental disaster would have on the ability to access Machu Picchu. The closest major airport is Alejandro Velasco Astete International Airport in Cusco, Peru—more than 75 kilometers from the center of Machu Picchu. To make response more timely for an environmental disaster, the site has organized evacuation systems and emergency services to provide initial response to a fire.

The absence of environmental impact assessments, security surveys, and studies of alternative access roads to the Inca Trail, as well as incomplete physical and legal tenure of the lands, create vulnerabilities for a multitude of stakeholders—including the Regional Government of Cusco, the National Institute of National Resources, the National Institute of Culture, the Machupicchu Electric Generation Company, and Peru Railroad—within a complicated management system.

The Security System

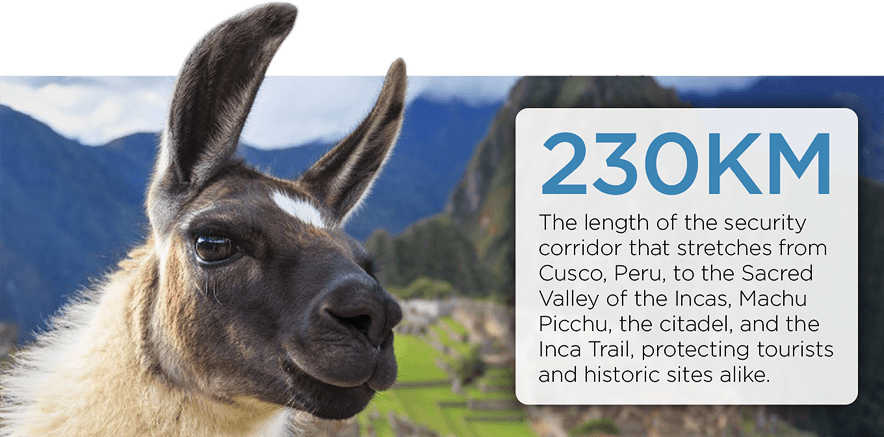

The tourism authorities in the Cusco region signed agreements in June 2014 to increase the safety of national and foreign visitors, as well as increase the care for the archaeological site of Machu Picchu and the Inca Trail.

Their actions established a 230-kilometer security corridor that includes the city of Cusco, the Sacred Valley of the Incas, Machu Picchu, the citadel, and the Inca Trail. This territory is continuously monitored by a control center manned by the tourism police.

The control center uses a digital communication system that allows tourism police to talk to agents in vehicles—and those on foot patrol—to respond to emergencies that may arise at the site. They are also supported by strategically placed high definition security cameras and a drone system.

Given the recent incidents of damage to the site and infiltrations of tourists at closing time, 30 thermal cameras will also be placed in strategic access points. Machu Picchu will use thermal cameras on drones to fly over the park to observe tourists and monitor for fires.

Cameras were also placed in key locations on the 43-kilometer Inca Trail. This video surveillance system allows emergency personnel to rapidly respond to weather and medical emergencies. The National Police of Peru also has access to the system—in real-time—and law enforcement has a helicopter fleet used by trained personnel to respond to emergencies at Machu Picchu. The Deconcentrated Director of Culture of Cusco also greatly increased the number of security guards at the site to prevent vandalism and other damage to Machu Picchu.

Inside the park, tour guides lead all tourists on their visit; these tours are monitored, and paramedics are on call to assist should someone become injured while visiting. Machu Picchu also has its own medical post to provide initial treatment to visitors while awaiting evacuation to a hospital.

There are approximately 200 security agents from various jurisdictions who can respond to Machu Picchu in the event of an emergency. Some of them are uniformed personnel, such as at the entrance to Machu Picchu, but many others are in plainclothes to work incognito and conduct follow-up and intelligence work. These plainclothes officers are also there to help prevent crimes before they occur.

With the use of this undercover police system, it has been possible to detect tourists damaging the heritage site, taking drugs, and infiltrating at night, as well as trying to steal parts of the park’s rocks. These thefts can be especially damaging to Machu Picchu because it is constructed out of a material the Incas created by dissolving rock. Fracturing the rocks damages the construction of the citadel.

Authorities also created the Tourism Police Peru application that visitors can download to their smartphones. The application, which is free to use, can send reports to the tourism police’s control center. Users can open the application to report an emergency; the report automatically includes users’ location data to generate an immediate response from security units closest to their position.

COVID-19 Effects

Machu Picchu was closed to international visitors on 16 March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It reopened on 1 July with a maximum of 675 Peruvian tourists allowed in per day—far below the roughly 5,000 per day that visited the site during the high season before the pandemic began.

Restrictions have also been placed on the number of visitors per tour offered at Machu Picchu. There are four tour options, which can have up to 75 people in attendance for one hour and 20 minutes. Visitors also must practice social distancing and avoid excessive contact with others while at the site.

Herbert Calderon, CPP, PCI, PSP, is security director, metro subway line 2 in Lima, Peru. He is the senior regional vice president of ASIS International Region 8 and a past president of the ASIS LIMA, PERU Chapter.