Flying Over Fire

About four years ago, the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) saw a video clip, likely shot illegally, of a gas explosion in Harlem. The video was captured by a camera on a drone.

This aerial view over city buildings sparked an idea for the department: what if it could have similar drone video during every fire it responded to—as the fire was being fought?

"The incident commander is on the ground like a general calling all the shots. He's got people in the building doing searches. He's got people on the roof. He's the guy making decisions with the most information," says Tim Herlocker, former director of the FDNY Emergency Operations Center. Enhancing that commander's situational awareness with a drone would allow him to safely navigate a team of firefighters in and around the fire, especially on those hard-to-see rooftops.

When a fire strikes in the middle of the night, "some of our most senior chiefs have to start making decisions—'Do I have to go to the fire? Do I have to respond back to our headquarters?'" Herlocker notes. "And being able to actually see what it looks like—the color of the smoke, the volume of the smoke, the flames, whether they're trying to save it from moving to an adjacent building—all those things require experience honed over years as a firefighter."

The FDNY had been streaming helicopter video to the incident commanders for a number of years under contract with the New York Police Department and local news stations. "All of the options were good, but as technology progressed, we knew that we needed constant, persistent aerial surveillance of fire events," Herlocker says. Drones would provide much more flexibility, like the ability to hover directly over a fire or focus on a particular part of the blaze.

With the proliferation of drones, obtaining the right unmanned aerial vehicle was possible, but the department ran into another obstacle. "About 65 percent of the airspace in New York City is what's called Class B airspace," Herlocker explains, "and it's the most restricted airspace in the country." Under federal airspace rules, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) does not allow drones to fly within five nautical miles of any U.S. airport. New York City is within that range of three major airports: LaGuardia Airport, J.F.K. International Airport, and Newark Liberty International Airport.

Because of FAA rules, "we realized the program wasn't going to work, so we shelved it," he says. However, about six months later, the department approached the FAA with a new idea. "We went back to the FAA, and we said, 'We need to fly in your restricted airspace and we need to do it day and night on short notice, but we're going to mitigate the threat to your airspace by tethering our drones to the ground,'" he says.

The FAA agreed to the idea, and the FDNY began looking for a vendor that could meet its technological requirements. "We went searching for technology. We had a rough idea of what we wanted. There truly are only a handful of vendors that do purpose-built tethered devices," he says.

The FDNY wanted a unit that was not only tethered by a thin cord to a power source on the ground, but that could deliver instantaneous, high-definition or infrared video.

Most battery-operated drones are too lightweight to remain in flight for longer than a few minutes, so the tether would be a continuous power source. This would allow the drone to hover for hours on end. The FDNY also wanted the drone to remain directly over the anchor port where the drone takes off, but without using GPS. In an urban environment like New York City, metal structures and magnetic fields can throw off the vehicle's navigation system. "GPS signals can bounce off buildings, and the drone can chase a [wrong] signal and get out of position—so it's a tough environment to fly in," Herlocker says.

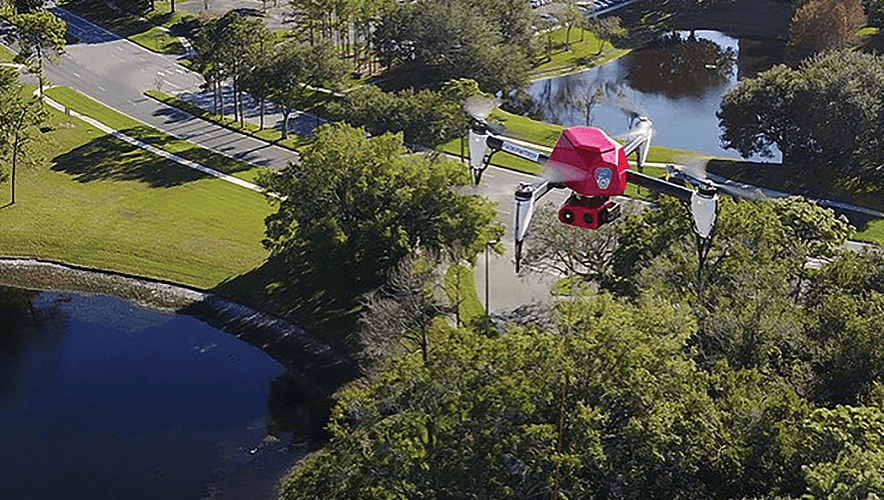

The FDNY selected Hoverfly Technologies of Orlando, Florida, which provided an eight-pound drone with a thin tether cord. The department began a pilot phase of the program, which lasted six months. "We've done a lot of testing, we've made a ton of mistakes, we've corrected technology," he says. The program began flying missions in March of 2017, and had flown 26 fires as of December 2017.

The department currently has three drones, which are deployed for second alarm or greater fires (the number of alarms indicating the severity of the fire). Video of the fire from the drone's HD and infrared cameras is streamed to the incident commander and other senior leaders in the department via a video recording network. The users receive the video directly to their smart devices by clicking on an encrypted link sent from Amazon's cloud.

FDNY firefighters who show interest or have a background in drones are trained as pilots. "We put them through an online training session that teaches the FAA standards, then at some point, when they have enough time on the device under supervision, we certify them." While it doesn't take much technical skill to pilot the drones, Herlocker notes, it does take a sound sense of judgment. "You have to decide, is it safe to put the drone up, is there too much wind, are there too many overhead obstacles, or is the fire worth the risk of putting it up?" he notes.

The drone is used in each mission to keep firefighters away from danger, show first responders where to direct water hoses, help them create vents in the roofs of buildings, and more.

The drone also helps with ladder placement. In the spring of 2017, the department was fighting a five-alarm fire at a large apartment building. "The drone hovered in place for three hours at 130 feet. The firemen were using the drone to move ladders around and hit different hot spots on the roof," with a precision that helicopter video would not have provided in the past, Herlocker explains.

Herlocker notes the department's relationship with the FAA has also become an asset to fighting fires. The department is required to call and clear each drone flight in advance. Recently, the FDNY had to put through an emergency request when a fire was within one mile of LaGuardia airport. "We couldn't even finish the sentence before the FAA operator said, 'We were wondering what took you so long—you have permission to go.'"

In the future, the FDNY hopes to expand the drone program to include several vehicles with ready-to-deploy drones that nest on top. The department is also looking into free-flight drones to fly inside of burning buildings, with the ability to make tight turns and assist in rescue operations.

While Herlocker says it's hard to measure exactly what the drone program has prevented, including injuries to firefighters and buildings from destruction, it has undoubtedly benefited the department. "We want the incident commander to have just a little bit better view to make safety calls and to fight the fire more efficiently," he says.

For more information: Lew Pincus, [email protected], www.hoverflytech.com, 407.985.4500