Security Training Saves Synagogue Hostages

On Saturday British national Malik Faisal Akram allegedly brandished a handgun during services at the Congregation Beth Israel, a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, a suburb between Dallas and Fort Worth, before taking Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker and three congregants hostage.

The suspect held the hostages for 11 hours in a standoff with authorities, threatening to kill the hostages if Aafia Siddiqui was not released from prison. U.S. armed forces arrested Siddiqui in Afghanistan in 2008 and she was eventually convicted in 2010 of attempted murder for an incident that occurred while she was in custody. Several terrorists and kidnappers have previously demanded her release.

An FBI hostage rescue unit from Quantico, Virginia, was quickly mobilized and flew to the scene in Texas. Akram reportedly released one of the hostages, and the others managed to escape after Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker created a distraction. The FBI team stormed in and Akram was killed, with the exact circumstances of his death still being investigated.

A powerful, must-watch interview with Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker of Congregation Beth Israel in #Colleyville. His actions were nothing short of heroic. https://t.co/HjLVnwyJtu

— Jonathan Greenblatt (@JGreenblattADL) January 17, 2022

Investigations into the incident are ongoing. Teenagers in the United Kingdom believed to be Akram’s sons have been held for questioning. The BBC reported that Akram was a person of interest to British security in 2020, a distinction that was since reclassified and he was no longer considered a threat.

In interviews after his escape, Rabbi Cytron-Walker said the security training he and his congregation received was instrumental in their escape and ending the standoff. Cytron-Walker said that during their hours-long captivity, the hostages tried to maneuver their position so that they were near an exit.

As the standoff wore on, one of the hostages, Jeffrey Cohen, told The Washington Post that Akram grew increasingly agitated and ordered them to kneel, execution style. The hostages refused.

“I was not going to let him assassinate us,” Cohen said. “I was not going to beg for my life and just have him kill us.”

Akram allegedly backed down and set his gun to his side as he poured a drink into a cup. Cytron-Walker then grabbed a chair, shouted to his fellow captives to run, threw the chair at Akram, and then ran himself. The three captives made it outside, and the FBI strike team used the opportunity to storm the building.

“Over the years, my congregation and I have participated in multiple security courses from the Colleyville Police Department, the FBI, the Anti-Defamation League, and the Secure Community Network," said Cytron-Walker in a statement. "We are alive today because of that education.”

Cohen had been a student in Pittsburgh when a gunmen killed 11 people at the Tree of Life synagogue in the city, so when underwent security training at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville he was highly attentive.

“I really never thought we’d use [the training],” Cohen told the Post.

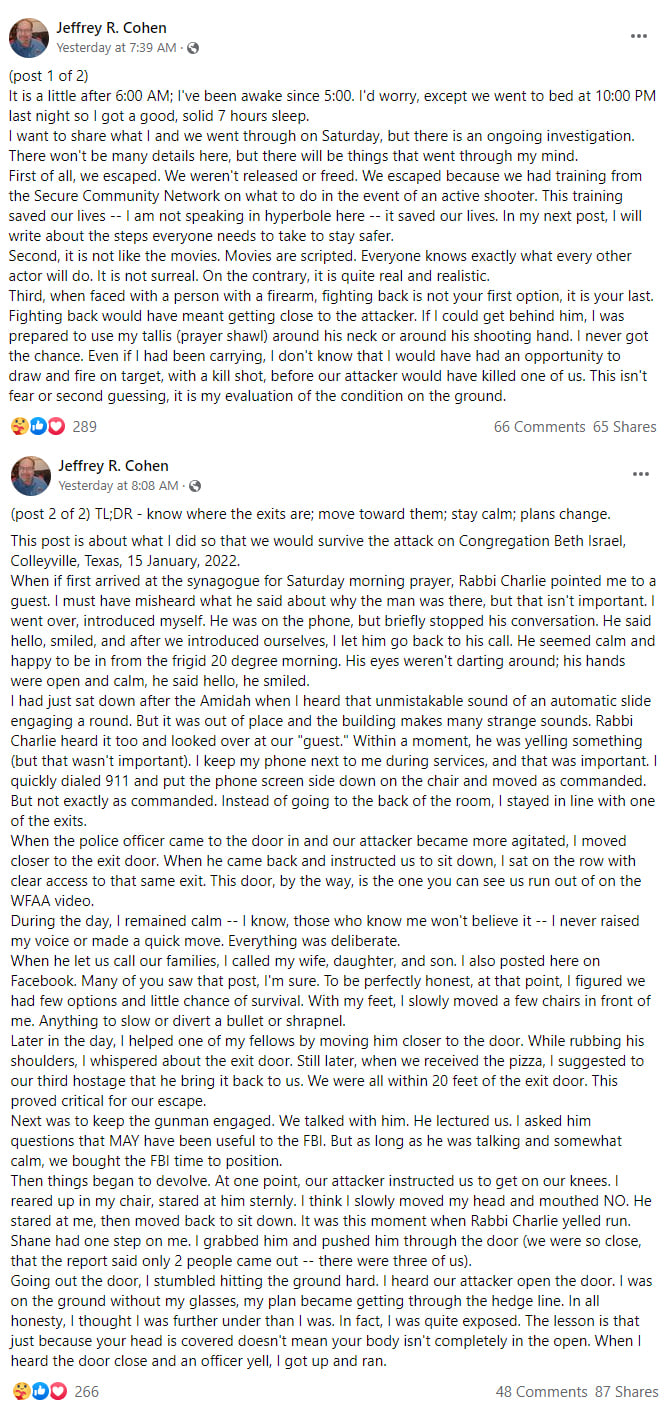

In a pair of Facebook posts, Cohen shared his experience: “…we escaped. We weren’t released or freed. We escaped because we had training from the Secure Community Network on what to do in the event of an active shooter. … If I could get behind him, I was prepared to use my tallis (prayer shawl) around his neck or around his shooting hand. I never got the chance.”

Incidents of threats and violence at synagogues and other Jewish centers in the United States have increased during the last several years. In an interview with The New York Times, Mitchell D. Silber, executive director of the community security initiative at the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York said that, “More and more, the Jewish community has accepted that unfortunately what it means to be a Jew in the United States in 2022 is that your institution needs to have guards, checkpoints and security.”

In a personal essay published Monday by The Atlantic, Juliette Kayyem, faculty chair of the homeland security program at Harvard and a former assistant secretary for homeland security, described her experience as an Arab American with a Jewish husband raising Jewish children and being asked by her family’s synagogue to help plan security.

“The very existence of the security committee was a sign of concern about anti-Semitism and hate crimes,” she said. “…The members of the committee were of course aware of the threat, but they had no background in how to counter it. I explained that, generally, the overall goal is to minimize risks while maximizing defenses. But minimizing risks is not easy for one temple to do alone, so the community would have to focus on building defenses.”

She detailed a typical security checklist, starting with outer perimeter issues, such as “fencing or walling off areas exposed to busy streets,” and employing security guards for large gatherings. She also suggested installing video surveillance and conducting active assailant training. The committee was with her. Then she talked about access control, and that’s when she realized this was a different endeavor.

But what if the essence of a place is that it is defenseless? What if its ability to welcome others, to be hospitable to strangers, is its identity? What if vulnerability is its unstated mission? That is the challenge I hadn’t considered. ...In the U.S., for a Jewish congregation to become a fortress would seem too militaristic, too aggressive. To make a soft target harder would more likely change the target than deter the attacker.

In security, we view vulnerabilities as inherently bad. We solve the problem with layered defenses: more locks, more surveillance. Deprive strangers of access to your temple, I urged the committee members, and have congregants carry ID. They would have none of it. Access was a vulnerability embedded in the institution, and no security expert could change that—we do logistics, not souls.

In what continues to be the seminal work in the area, the ASIS Cultural Properties Community wrote a whitepaper on the subject, Recommended Best Practices for Securing Houses of Worship Around the World for People of All Faiths. The document, discussed the balance that houses of worship must achieve and that Kayyem struggled with.

"Each congregation is tasked with the challenge of creating a safe place to worship. Various security precautions can be implemented in a non-intrusive manner, completely unknown and unobserved by congregants," according to the whitepaper. "For example, implementing a 'Welcoming Committee' that includes individuals observing and welcoming people as they enter the facility will basically be unnoticed as a security program, yet it is highly effective when the members are trained in security detection."

Jeffrey A. Slotnick, CPP, PSP, is president of Setracon and a member of the ASIS North American Board of Directors. In addition, he has worked with Jewish communities on security for decades. He helped develop Safe Washington: A Jewish Community Coalition to Keep Washington Safe after an attack on a synagogue in Seattle in 2006. The template used to create Safe Washington has been replicated in many communities across the United States, including Dallas.

In an interview with Security Management, Slotnick says “security and openness are not mutually exclusive. You can have passive but effective forms of security. You can be open and welcoming and be security conscious.”

He emphasizes that security programs are most effective when they prevent incidents from occurring, so he also advocates the usher/greeter role in security of synagogues and other houses of worship.

“Any type of training in pre-operational surveillance, identifying potentially suspicious behaviors, and just understanding what is going on—what potential vulnerabilities there are is vital,” he says.

He notes he has no inside information and does not know what the investigation of the Colleyville incident will reveal.

“When you study after action reports on these types of incidents, you usually see that there were three or four opportunities to identify and interrupt the behavior before it happened," Slotnick says. "But that’s only going to happen if you’ve had training and you know how to react to the indicators.”

In the Safe Washington training for ushers and greeters at religious services, it includes the following advice on suspicious behaviors:

- Ushers and greeters have a responsibility to be aware of and contribute to our collective safety. One way to do this is by knowing what to do if you witness behavior that seems suspicious to you.

- Generally, you should not engage a person who is acting suspiciously. However if others are around, and you feel comfortable doing so, you can approach the person and ask, “Can I help you?” If the person legitimately needs help, they will appreciate the offer. If not, then they will know that they have been noticed, which may prevent potential criminal activity.

- Report suspicious behaviors immediately. Don’t make judgments about what may or may not be a serious situation and don’t assume that someone else has called the police.

In addition to the welcoming committee and training of ushers ideas, the ASIS whitepaper has several suggestions for access control measures while still being welcoming, such as limiting points of access and establishing different zones of security for different parts of the facility.

Finally, Slotnick notes that often after such an incident, particularly one that includes a calling card for radicalism, such as the call for the release of Siddiqui, other radicals may plot copycat incidents.

“Now is the time to review your security procedures and policies,” he says. “Are the doors locked and the lighting on? Are the windows closed? You don’t necessarily have to post a guard at the door, but it’s a good time to review your awareness training and re-emphasize the things you’ve established to keep the community safe.”