Combating Complacency: Lessons Learned from the 1994 AMIA Bombing in Argentina

With more than 200,000 members, the Jewish community in Argentina is the largest in Latin America, and the sixth largest in the world; only Canada, France, Israel, the United Kingdom, and the United States have larger Jewish populations. Buenos Aires City, Argentina’s capital, is home to more than 200 sites dedicated to Jewish life, including synagogues, schools, yeshivas, and sports centers.

The Jewish people first came to Argentina from Russia, escaping famine and anti-Semitism in the 19th century. In the 1930s, they came to escape a hostile Europe. Following the Holocaust, they fled from horror and looked to Argentina for a new horizon. While Argentina provided a safe harbor, it was not without threats, especially as the years went by.

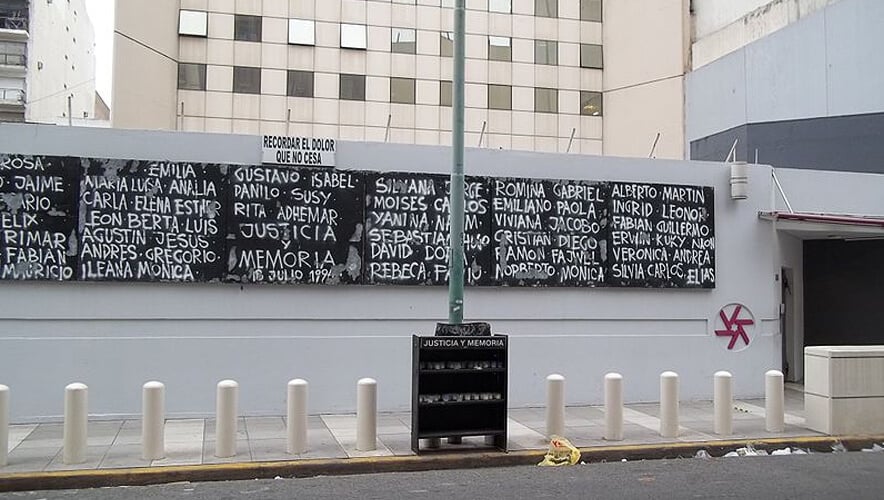

At 9:53 a.m. on 18 July 1994, a truck bomb exploded at the AMIA building, killing 85 people, injuring hundreds, and destroying the building. AMIA is a central Jewish institution, responsible for managing cemeteries, coordinating Jewish education, and overseeing a job bank. It sits in the center of the neighborhood known as Once, a traditional Jewish area that is home to kosher sites, synagogues, schools, and many Jewish-owned shops.

The 1994 attack was not the first to affect the Jewish people of Argentina. Two years prior, in March 1992, a car bombing at the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires killed 29 people.

Those were painful and sad times. The Jewish community was not the same. Parents feared sending their children to school and to youth centers. Buildings were not prepared to hold activities in a safe manner. Security personnel was not available to guard institutions. The Argentine State was not prepared to assist.

“To this day, not a single person is in prison for this horrific crime.”

The security organization of the Jewish community had to rethink everything.

The Jewish representative institutions created a Central Security Office to assess every aspect of community security. Each building was analyzed and hardened. Jewish institutions implemented standoff means, first through cement-filled barrels and later through more permanent reinforced concrete bollards. Each facility incorporated a security chief and guards, all Jewish. The Central Office was in charge of vetting, recruiting, training, and auditing personnel and activities.

Volunteers from the community guarded events and synagogues when professional security was not available.

Cameras, walls, fences, mantrap doors, and bulletproof glass were installed, and security procedures were implemented among the different schools, social clubs, and synagogues.

In time, the police started guarding Jewish buildings around the clock.

The Jewish community in Buenos Aires then developed a Community Emergency Plan. The plan assessed the main threats to Jewish life and established the response efforts to each of those, the impact on all institutions, the role of professional security personnel, the role of volunteers, the emergency security operation center’s (SOC) mission, and the creation of a backup SOC outside of the central Jewish security building.

A remembrance event is held every year for the 1994 attacks. Several thousand people gather and say the names of the dead. Community leaders, friends, and family of the deceased ask for justice. To this day, not a single person is in prison for this horrific crime.

The remembrance event is held at the new AMIA, rebuilt on the same site as the previous one, with modern and robust security. The events themselves are considered targets, and they are scrupulously protected.

I was a volunteer for the Jewish Security Organization for 16 years, and I have worked professionally in Jewish security as an auditor, instructor, and executive director of the security organization. I worked in the new AMIA building for seven years, spending my time with people who survived for days under the wreckage in the aftermath of the attack.

When I talk to people from the Jewish community who were born after the attack, their memories of the event and what came afterward are weak. Weaker still are the memories of those who are not Jewish. Argentinean society is forgetting. Its memory is fading. And so is its vigilance.

Each year, less and less budget is designated to security for the Jewish community. The Central Office has reduced its staff and activity during the last five years, impacting the services and products provided to security professionals. Training has also been reduced.

The emergency plan has also suffered; updates and drills are less common. Most Jewish institutions face economic constrains and have reduced security personnel and coverage. This affects the capacity to implement proper controls, which when added to the willingness of organizations to be more welcoming to outsiders, affects the stringency of screenings and controls for visits and vendors.

Increasing urban security challenges mean police personnel are no longer at fixed locations like synagogues. They patrol the area instead. This shows the neighborhood that police protect everybody, but the adjusted security posture lifts some protections for Jewish sites.

“The lack of expertise in terrorism phenomena is a voiced secret. ”

World events from 9/11 to today demonstrate that violence and extremism are a prevalent threat, with the risk of right-wing terrorism rising globally. But in Argentina, people are starting to drop their guard. Security is no longer a priority, and attention is scarce.

In the intelligence community, the lack of expertise in terrorism phenomena is a voiced secret.

Civil unrest grows worldwide, the uncertain effects of the COVID-19 pandemic loom, and the conflict between Israel and Hamas has translated into demonstrations in Argentina. Palestinian organizations and left-wing parties recently rallied in front of the Israeli Embassy building in Buenos Aires.

During the early days of the Israeli–Hamas conflict in May 2021, anti-Semitic graffiti was sprayed on a Jewish school in the city of Bahia Blanca in Argentina; it read: “Jewish Rats—We are going to kill you,” Argentine news platform Infobae reported.

Anti-Israel graffiti sprayed on a traditional Jewish neighborhood of Villa Crespo in the city of Buenos Aires by a right-wing nationalist group read: “Israel intruder” and “Israel genocide,” according to Infobae. On the street center of the province of San Juan, another graffiti read “Be a patriot, Kill a Jew”—a traditional war cry by traditional right-wing anti-Semitic groups in the 1970s.

Antisemitic attacks repeat all over the country. In April 2021, the FBI and the Argentine Federal Police arrested several men charged for an alleged connection to ISIS. One of the people under investigation said that he had instructions for assembling explosive devices, according to LA NACION.

Also in April, in the Province of Tucumán, two men were arrested after Argentine police determined that an attack against a synagogue was imminent. During the investigation, authorities seized several firearms and knives, in addition to Nazi literature and symbology.

As the time since the last severe attack grows, we are normalizing a reality that nothing tragic happens. Until it happens again.

Alejandro Liberman, CPP, is a security professional and ASIS member with almost 20 years of experience. Liberman owns consulting company GLOHER GROUP, leading security consulting, training, and investigations in South America. From 2008 to 2012, Liberman was the head of the Jewish Security Office in Argentina and has been involved in Jewish community security for 15 years. He is advisor to the Latin American Jewish Congress on security, crisis management, and terrorism. Liberman served as the president of the Buenos Aires, Argentina, ASIS Chapter in 2020 and 2021.