How the Internet Makes Hacking Humans Easier

Not too long ago, there was no social media. Go a little further back in your mental time machine and you won’t find cell phones or widely and freely available Internet access. It’s a strange concept to many people now—especially when you factor in that, according to GSX 2021 presenter Erik Qualman, one in three people would rather give up sex than his or her smartphone.

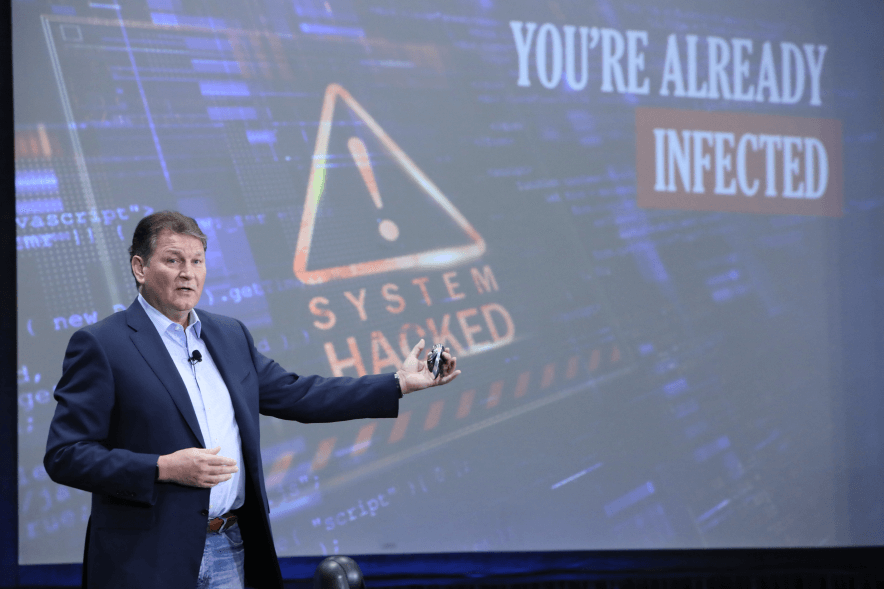

The Internet revolution does not appear to be stopping, and that includes advancements within the security industry, from Internet of Things (IoT) devices to Zoom, as former CIA intelligence officer Peter Warmka, CPP, noted “Confessions of a CIA Spy: The Art of Human Hacking” at GSX 2021.

And while there are benefits that come with these advancements, Warmka, founder of the Counterintelligence Institute, LLC, adds that attackers can use these new abilities against people and companies. But savvy attackers do not simply work from afar, behind a computer screen; with the amount of information that an organization places online about itself and its staff, threat actors can use that data to gain access into an organization by cultivating inside help, or, as Warmka calls it, by hacking humans.

When Warmka worked for the agency and needed to cultivate a source of information from within an organization, he said he would focus on first identifying potential allies. These were typically entry level staff, so Warmka would first have to seek out an organizational chart.

But today, that’s as easy as logging into LinkedIn, which, along with other social media sites are “a treasure trove of information,” Warmka said.

While LinkedIn offers threat actors not only enough information to map out where staff land within an organization, it also provides the economic and professional history of each person. Users also list any certifications, licenses, and education they have received—giving one a glimpse into his or her career aspirations.

Once an attacker spots a potential ally on LinkedIn, he or she can try to find them on Facebook or Instagram. These social media sites tend to provide additional insight into that person’s relationships, interests, where he or she has already or wants to travel to, and other details that paint a more complete picture of the target’s socio-economic status.

And over on Twitter, a threat actor can delve a little deeper into the person’s mind—tweets usually reflect a user’s opinions, political and other beliefs, and even pet peeves.

Put together, a person’s social media footprint can reflect a pattern of his or her life that allows an attacker to create a profile and consider his or her ambitions and weaknesses. It can allow these threat actors to befriend and beguile these targets by leveraging what motivates that person, his or her vulnerabilities, or a combination of the two.

Humans are susceptible to such social engineering not because we are unintelligent, but because we want to trust others, Warmka cautioned.

“Once you believe I am who I say I am, I can collect incredible information from you,” Warmka said.

Sara Mosqueda is assistant editor for Security Management, parent publication of the GSX Daily. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @XimenaWrites.