Frankenstein Fraud: How Synthetic Identities Became the Fastest-Growing Fraud Trend

Fake it 'til you make it. Or until you steal more than $1 million. That was the case for more than 11 individuals charged for their alleged roles in a synthetic identity fraud scheme that caught the eye of law enforcement and led to a nationwide investigation in the United States.

It started with the creation of synthetic identities—made from stolen Social Security numbers paired with different names, addresses, and dates of birth of other real people. These Social Security numbers were chosen because they didn’t have an associated credit history or they were unlikely to be actively monitored—i.e., numbers for children, recent immigrants, elderly individuals, incarcerated people, and even dead people.

The fraudsters then took steps to make these synthetic identities seem legitimate. They applied for phone numbers; set up email, reward card, and library card accounts; and allegedly put the identities into public databases used by financial institutions to verify identity information.

Adam D. Arena, 44, supposedly furthered the scheme by creating shell companies that reported the synthetic identities to credit reporting agencies as if they were real customers with good credit history over several years—boosting the fake identities’ credit scores even more.

All of this was done to then build credit on the synthetic identities to obtain loans and credit cards from financial institutions, including USAA Bank, Navy Federal Credit Union, First National Bank of Omaha, and Suffolk Federal Credit Union. The accounts associated with these identities were then maxed out and never repaid.

The activity eventually caught the eye of the New York Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office of Financial Investigations and Money Laundering Bureau and the Suffolk County Police Department’s Financial Crimes Unit. They began investigating suspicious activity at several banks and credit unions on Long Island, which revealed that 13 individuals created and used more than 20 synthetic identities to obtain loans and credit cards from 19 different financial institutions to steal more than $1 million.

“This is an extremely complex crime, and it can be very difficult to identify the perpetrators, but the team who is investigating and prosecuting this case meticulously followed the evidence and unraveled this scheme, which has far-reaching impacts on everyday citizens,” said Suffolk County District Attorney Timothy D. Sini in a press release announcing the charges against the 13 alleged conspirators.

Synthetic identity fraud is not new. It’s a fraud trend that has been around for decades that was often carried out in person before shifting to take advantage of the Internet. And it has grown rapidly in the 21st century. Recent research from Aite Group, sponsored by consumer credit reporting agency TransUnion, found that synthetic identity fraud for unsecured U.S. credit products totaled $1.8 billion in 2020 and will grow to $2.42 billion in 2023.

“These estimates are conservative—if the amount of credit charge-offs attributable to synthetics are indeed universally in the 10 percent to 15 percent range, as indicated by some of the issuers and lenders interviewed for this report, then the losses could be as high as $6 billion,” according to Aite’s report, Synthetic Identity Fraud: Diabolical Charge-Offs on the Rise.

And while the cost this fraud poses to organizations, financial institutions, and individual victims is high, it also has major ramifications for national security as officials struggle to detect fraud and hold criminals accountable for it.

“If you’re not responding to the fraud against hard-working people, you’re eroding the compact between the people and the state at a fundamental level—and that has broader consequences for society,” says Helena Wood, associate fellow, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies.

Synthetic Identity 101

“Fiction is the truth inside the lie,” wrote Stephen King, the master of horror who often uses his novels to address real fears through fantasy. He was on to something—if you want someone to believe a falsehood, it helps to tether it to something true.

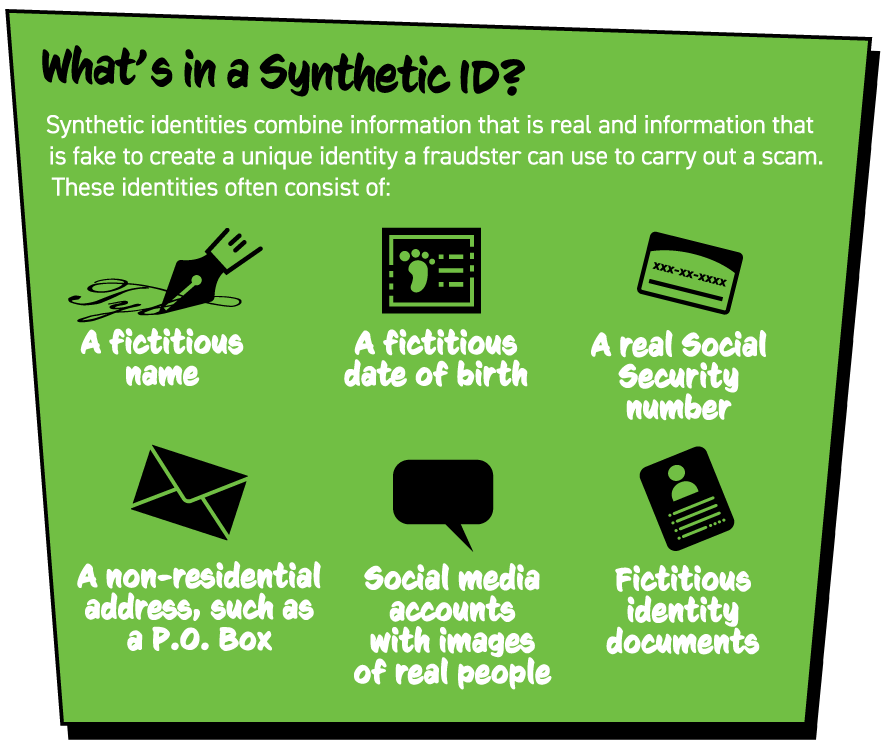

Maybe that’s why synthetic identities are appealing to fraudsters and difficult to detect for those taken advantage of by them. Synthetic identities are generally based on a real Social Security number (SSN) or credit privacy number mixed with an address and other personal information, such as social media profiles using photos of real people.

There are other tell-tale characteristics that could indicate the use of a synthetic identity, such as multiple account applications from the same IP address or device, multiple identities with the same Social Security number, multiple applicants with the same address or phone number, applicants with Social Security numbers issued after 2011, and addresses near large international airports or shipping areas.

And these identities can be built out in three different ways, according to a fact sheet by credit reporting agency Experian: building a fraudulent credit profile over time through applications and inquiries, creating false credit reporting agency updates, or gaining access to legitimate accounts and using their user addition processes.

“Sophisticated criminals put a great deal of effort into creating convincing, verifiable personas they can use to commit various types of fraud, ranging from acquisition of financial instruments to healthcare benefits, utility services, and tax filings and refunds,” Experian said. “Information attached to synthetic IDs can run several levels deep, including public record demographic data, credit information, documentary evidence, and social media profiles that contain photo sets (and other historical details) intended to deceive.”

And because synthetic identities combine personal data from multiple individuals, no one is typically alerted to charges on an account because they are not tied back to a real person—the institution that provided the service the synthetic identity used is considered the first victim.

“But this isn’t always the case. Of grave concern is the fact that minors who may legitimately be issued SSNs that are being used to build synthetic IDs will find life as an adult much more challenging, and by default will be victims at some point,” Experian said. “As these individuals become credit-active adults, they will find themselves subjected to heavy risk-based suspicion and a lack of positive and trusted identity verification, particularly with online and mobile services.”

In an analysis in 2019, the U.S. Federal Reserve found that synthetic identity fraud is the fastest-growing type of financial crime in the United States. It cost U.S. lenders $6 billion in 2016 and was responsible for 20 percent of credit losses in 2016.

One reason that synthetic identity use may be growing is because of the increasing amount of personally identifiable information (PII) compromised due to major data breaches over the past 10 years. Between 2017 and 2018 alone, the volume of PII data exposed in breaches increased by 126 percent—with more than 446 million records exposed—the Federal Reserve said.

“Since 2013, we’ve seen more than 70 billion data records breached,” says Julie Conroy, research director for Aite Group’s fraud and anti-money laundering practice and author of its report, Synthetic Identity Fraud: Diabolical Charge-Offs on the Rise. “It’s a massive number, and it’s not all PII stuff—it’s also credentials. But there’s a lot of PII, which then gives these organized crime rings fodder as they’re putting together piecemeal identities, or Frankenstein identities.”

Synthetic identities tend to be more prevalently used in the United States than elsewhere in the world because of the emphasis on static personally identifiable information to verify someone’s identity, according to the Federal Reserve.

Changes by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) may have also inadvertently made it easier for fraudsters to use someone’s Social Security number for a synthetic identity. In June 2011, the SSA started randomly assigning Social Security numbers to protect them and extend the pool of available nine-digit numbers.

“Randomization eliminated the geographical significance of the first three digits of the Social Security number (also called the area number), which previously helped financial institutions determine an individual’s state of origin,” according to the Federal Reserve report Payments Fraud Insights: Synthetic Identity Fraud in the U.S. Payment System. “As a result of randomization, geographic checks are no longer effective for newly issued SSNs and it is more difficult to detect when fraudsters create synthetic identities using unissued or fabricated Social Security numbers.”

One effort that may help to address this problem is the SSA’s electronic Consent Based Social Security Number Verification Service (eCBSV), which rolled out in 2021. The service allows users to verify that the name, date of birth, and Social Security number an individual uses corresponds to the name, date of birth, and number in the SSA’s system. The service has a select number of entities enrolled, including Navy Federal Credit Union, Experian, and Discover Financial Services, but it is expected to gain more over the course of 2021.

The Federal Reserve also identified gaps in the credit process that could create opportunities for fraudsters. An example of this would be a fraudster using a synthetic identity to apply for credit at a financial institution. The institution might reject the application, but in the process it would have created a credit profile associated with that synthetic identity.

“The new credit profile becomes the synthetic identity’s so-called ‘proof’ of existence,” according to the Federal Reserve. “The fraudster applies at a number of different financial institutions until an application is eventually approved.”

Once the application is approved, the fraudster will often use that associated account to increase the synthetic identity’s credit availability and credit score before initiating a bust out.

“A ‘bust out’ scheme is generally when someone applies for credit (credit cards, retail cards, home equity) using a synthetic identity,” explained Shari R. Pogach, regulatory paralegal, in a blog post for the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions. “They build good credit by making timely payments, obtaining credit line increases, and with increasing usage. They then max out all available lines of credit, with no intention of repaying, and drop the account. These then go into collections and turn into charge-offs and a loss for the financial institutions.”

Financial institutions may have been more vulnerable to these scams due to economic recovery pressure in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008, Conroy says.

“Credit issuers were opening their standards,” she explains. “They were targeting thin file and new credit folks, which made it easier to establish these synthetic identities.”

And once in the door, holders of these synthetic identities will nurture them, sometimes for years while their credit score rises, they obtain more access to funds, and secure a larger payout.

“The crime rings behind the bulk of the fraud are patient and will often build up synthetic credit lines over months or years before they bust out,” Conroy wrote. “Once on the books, synthetics are often written off as credit losses. This represents a double whammy for the credit grantor; not only does it absorb the loss, but it also expends valuable resources trying to collect from someone who doesn’t exist.”

Detection Woes

Detection of synthetic identities often relies on financial institutions following Know Your Customer (KYC) processes and regulations, including an in-person check.

In the United States, the Bank Secrecy Act and the USA Patriot Act—primarily focused on money laundering—also require financial institutions to identify customers, maintain appropriate financial transaction records, and report suspicious behavior to government agencies. These checks can help detect the use of a synthetic identity, but financial institutions can also use technology help verify identities and reduce operational costs. They could use, for instance, machine learning to identify and model expected customer behavior patterns and create alerts for anomalous behavior that could indicate fraud.

“As fraud tactics continue to evolve quickly, these tools need frequent recalibration to remain effective,” according to the Federal Reserve. “Furthermore, automated lending processes may need adjustment and updates, since they can provide another avenue for fraudsters to receive credit. For example, a synthetic with a high credit score could be targeted by an institution’s marketing campaign and receive a pre-approval offer for a new account.”

Another aspect of synthetic identity that makes it difficult to detect is the length of time over which it is used and nurtured. Fraudsters will craft the identity and take care of it over months or years to reach a higher credit limit, with Federal Reserve analysis finding that 70 percent of “suspected synthetic identity accounts are temporarily exhibiting typical consumer payment patterns—making them more difficult to detect.”

Unfortunately, many synthetic identity fraud scams are not detected until they reach the bust out phase and a financial institution’s collections team is unable to find an individual to pay the debt. The fraudsters’ success may even encourage them to repeat the scam or leverage financial institution policies in their favor.

“Busting out is not always a one-time event,” according to the Federal Reserve’s Payments Fraud Insights: Detecting Synthetic Identity Fraud in the U.S. Payment System report. “For example, fraudsters sometimes multiply their payouts by claiming they were subject to identity theft to convince financial institutions to reverse charges and reopen credit lines.”

Synthetic identity fraudsters may also take advantage of windows in the U.S. Fair Credit Reporting Act review period to “flood the financial institution with an overwhelming number of claims,” reducing the likelihood that the institution will complete its investigation in the required timeframe, the Federal Reserve found.

“Fraudsters know that many financial institutions establish dollar-value thresholds and automatically settle any fraud claims below that figure,” the Federal Reserve wrote. “These policies are in place to reduce the operational cost of investigations and promote a positive, seamless customer experience for legitimate account holders. Fraudsters can attempt to avoid detection by determining an institution’s threshold and disputing transactions in increments just below it.”

The Security Threat

Detecting synthetic identities is difficult. But finding, charging, catching, prosecuting, and convicting the people who create them is even more so. While the U.S. Department of Justice, Europol, and other law enforcement agencies put out press statements on fraudsters who were successfully identified and brought to justice, many more will never see the inside of a courtroom or be held accountable for their crimes.

In a recent RUSI analysis, Ardi Janjeva found that there were 3.7 million reported incidents of fraud in England and Wales between 2019 and 2020, but only 1 percent of the UK’s policing response is devoted to fraud investigations. This is all the more concerning because fraud is tied to funding of terrorism operations and organized crime.

“Not only is fraud against individuals undermining the government’s ambition for the UK to be the ‘safest place in the world to be online,’ but fraud against business and the financial sector is undermining the UK’s financial infrastructure and the country’s reputation as a place to do business,” Janjeva wrote.

His assessment cited a report published by RUSI in February 2021, which took an in-depth look at the scope of fraud in the United Kingdom and the security ramifications of a perceived failure of addressing fraud schemes impacting individuals, businesses, and public bodies.

Reviews and personal experiences have shown that often in the UK when fraud was reported by victims, nothing happened, says Wood, who authored the RUSI report The Silent Threat: The Impact of Fraud on UK National Security with Janjeva, Tom Keatinge, and Keith Ditcham.

“If you’re burgled or mugged, you expect a police response,” she adds. “Surveys in the UK for fraud victims have shown that they don’t even bother to report it to the police because they didn’t expect a response.”

And institutions—unless required to under regulations—may also be reluctant to report fraud due to concerns about perception and brand damage, Wood says.

Yet fraud is the crime that most UK citizens are likely to fall victim to, and “failures in the response to date have the capacity to undermine public confidence in the rule of law,” the authors explained in the RUSI report. “Its impact on the private sector has consequences for both the stability of individual companies and the broader reputation of the UK as a place to do business. The scale of fraud against the public purse has been described as a ‘heist on public services’ and has the capacity to undermine public faith and trust in government.”

One particular problem is the approach that it is up to the criminal justice system to hold fraudsters accountable. This is misguided, Wood says.

“This is not a problem we can arrest our way out of. It has to be a disruption-based approach to tackling fraud,” Wood explains. “Digitization of everyday life means that the threat comes from a different country than where victims are geographically located…we have to use tried and tested methods for other threats, like terrorism and organized crime, to disrupt fraud.”

For instance, RUSI argues that there should be a national security response to fraud with the UK’s National Security Council creating a commission for a “whole of system” approach to tackling it. This would include a national local-networked criminal justice response, opportunities for cross-

government collaboration, and a defined role for the private sector.

The RUSI paper also suggests that the National Police Chiefs’ Council commission a review to build “synergies between the specialist fraud and cyber capabilities within policing, including exploring the benefits of functional mergers.”

For instance, the United States recently took a similar measure when the U.S. Secret Service announced in July 2020 the creation of Cyber Fraud Task Forces to prevent, detect, and mitigate cyber-enabled financial crimes.

“In today’s environment, no longer can investigators effectively pursue a financial or cybercrime investigation without understanding both the financial and Internet sectors, as well as the technologies and institutions that power each industry,” according to a press release. “Secret Service investigations today require the skills, technologies, and strategic partnerships in both the cyber and financial realms. Nearly all Secret Service investigations make use of digital evidence, and the greater technological sophistication by bad actors has led to a proliferation of blended cyber-enabled financial crimes.”

Reinvesting and refocusing police resources to investigate fraud is necessary, Wood says, because it’s not an area that many departments want to devote themselves towards.

“We’ve all watched the cop shows,” she says. “Cops—for better or worse—like to chase people around in cars or get drugs or money. They don’t want to go through spreadsheets and bank statements and knit complex webs of shell companies together. It’s a cultural predisposition to go after the sexy stuff.”

Increased communication, threat intelligence sharing, devoted resources, and public–private partnerships between fraud investigators and cyber experts are all tools necessary to combat the rise of fraud and synthetic identity scams in a holistic way.

“There are substantial lacunas in the national understanding of the totality of the fraud problem,” according to the RUSI report. “Whether through better tasking of intelligence agencies, increased support for academic research, or better data-sharing and collaboration between the public and private sectors, gaining a better strategic understanding of the ways in which fraud manifests itself as a threat to society, as an organized crime threat, or as a funding stream for terrorism will be key to designing a new blueprint for the future response.”

Megan Gates is senior editor at Security Management. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @mgngates.