Research Finds Full Convergence Is Far from Commonplace

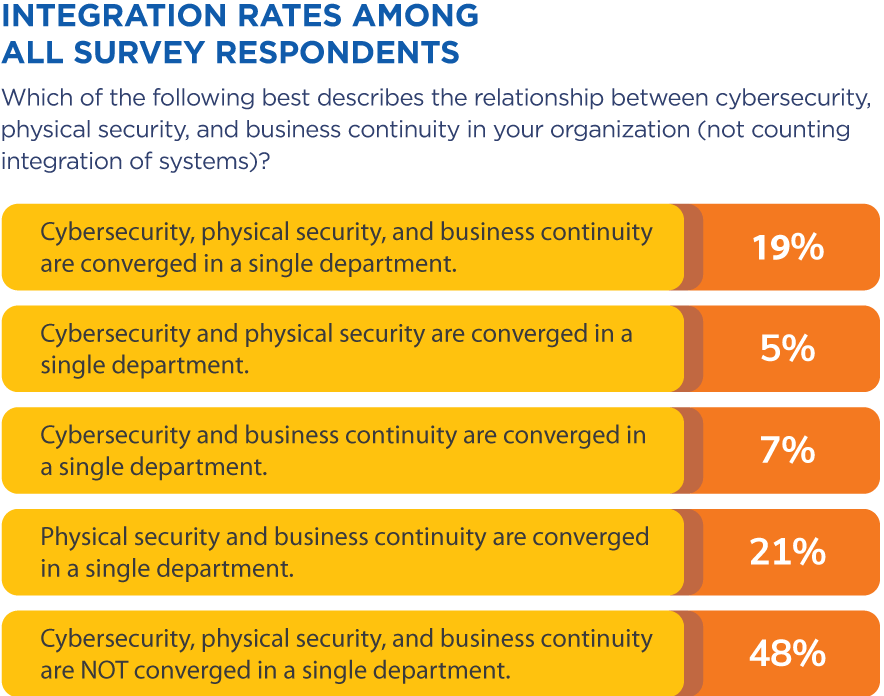

Everything that rises must converge. At least that’s what French philosopher-priest-paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin posited about spirituality. But convergence isn’t so inevitable from the more worldly perspective of corporate security departments. In fact, only about one-fifth of organizations in the United States, Europe, and India say that they have fully converged physical security, cybersecurity, and business continuity. And of those that haven’t converged at all, 70 percent say that they have no plans to do so.

These are two of the initial findings from recently published research from the ASIS Foundation, sponsored by AlertEnterprise, seeking to determine the extent of convergence in three key regions. The research provides some sorely needed data to a topic that has been addressed extensively, but only anecdotally, in the last decade.

More than 1,000 CSOs, CISOs, physical security directors, cybersecurity directors, business continuity heads, and crisis/disaster management leaders responded to questions about their states of convergence, barriers to convergence, benefits and drawbacks of convergence, and related topics—responses that were supplemented by about two-dozen in-depth interviews. The result is a seminal snapshot of how physical security, cybersecurity, and business continuity departments interact at organizations in the United States, Europe, and India.

Key Findings

Some of the most intriguing findings from the survey involve organizational type and size, reasons for not converging, benefits of converging, drawbacks of converging, oversight of a converged function, and models for effective collaboration and management absent full convergence.

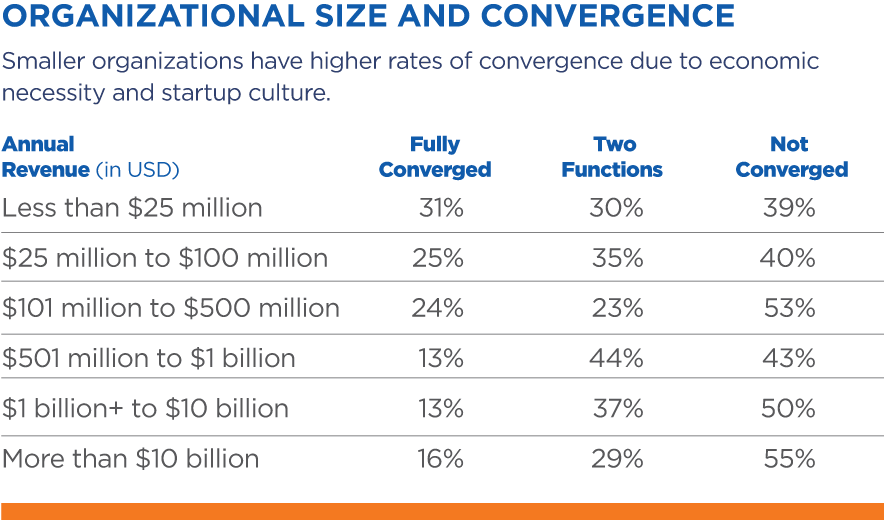

Organizational factors. Smaller firms tend to converge in greater numbers due to economic necessity and the “everyone is responsible for everything” nature of startups and small companies. Organizations grossing less than $25 million annually report a 31 percent rate of convergence. That percentage shrinks as company size grows, with a slight increase toward more convergence at very large companies. See the chart on page 48 for a breakdown.

Location also plays a significant role. Companies in Europe and India report a convergence rate of 23 percent each, compared to only 16 percent in the United States.

The extent of full convergence varies by industry as well. Of the verticals for which enough data was available to produce reliable results, utilities lead the way with 30 percent reporting that physical, cyber, and business continuity are converged. That’s likely because of the relatively small size and budgets of the utilities that responded to the survey. Other industries showing relatively high levels of convergence include financial services, hospitality, and technology/software at 19 percent each. At the other end of the spectrum are retail, healthcare, and engineering/construction, at 11 percent each.

Nonconverged firms. Nonconverged organizations were asked about what factors were discouraging them from converging and what factors might lead them to eventually converge. Difficulties in melding cyber, physical, and business continuity functions center around personnel issues and the perceived unique nature of cybersecurity. These challenges include different cultures and skills among converged units (41 percent); turf and silo operating traditions (41 percent); and the notion that separate security operations are needed (26 percent).

Nonconverged firms. Nonconverged organizations were asked about what factors were discouraging them from converging and what factors might lead them to eventually converge. Difficulties in melding cyber, physical, and business continuity functions center around personnel issues and the perceived unique nature of cybersecurity. These challenges include different cultures and skills among converged units (41 percent); turf and silo operating traditions (41 percent); and the notion that separate security operations are needed (26 percent).

Luring companies towards convergence, however, are: better alignment of security/risk management strategy with corporate goals (38 percent); advances in physical and cyber tech integration/security operations centers (28 percent); the promise of greater efficiency in security and/or business continuity operations (27 percent); and the potential for clear cost savings (21 percent).

Converged firms. Organizations that have converged physical, cyber, and business continuity overwhelmingly cite the advantages of that integration. In fact, 44 percent say that convergence hasn’t yielded any negative results.

A wide range of benefits include better alignment of security strategy with corporate goals (40 percent); enhanced communication and cooperation (39 percent); establishing a shared set of practices and goals across physical security, cybersecurity, and business continuity teams (35 percent); enabling the security staff to become more versatile and well-rounded (26 percent); helping the organization gain a more-efficient security operation (25 percent); and more visibility and influence with the C-suite and board (23 percent).

Nearly half (46 percent) of survey respondents say that convergence has at least somewhat strengthened their overall security function, and another 30 percent note that it has “greatly strengthened security.” Only 3 percent indicate that convergence has led to a weakened operation, and 14 percent say there was “no change.”

Leadership Counts

Detailed interviews show that organizations across industries and regions realize that having multiple security departments that don’t talk to each other or meet sparingly is unacceptable in an age of threats that defy traditional boundaries. Though many nonconverged organizations insist that their security departments meet frequently and work jointly on projects, the survey responses show that collaboration is closer at converged organizations.

For one international energy company, the path to convergence was charted when a new CISO was hired and immediately instituted a convergence plan. “He wanted a much closer connection between cyber and physical security,” says the firm’s head of physical security. “The main reason to converge is sharing of information in a combined area. Security is now so complex—physical information and cyber—that combining all the knowledge is very essential.”

A few negative consequences of convergence emerged from the survey, however. They include confusion over roles and responsibilities (29 percent), confusion over lines of reporting/communication (25 percent), and conflict and other personnel issues among converged staff (25 percent).

Also, creating a converged department requires talented people with the skills to make it happen. And, for many organizations, budgets and costs remain an issue.

Also, creating a converged department requires talented people with the skills to make it happen. And, for many organizations, budgets and costs remain an issue.

“When you look for someone with the cyber talent, there is the financial part to consider,” says the CSO of a European energy firm. “I need to pay a lot more to have a cybersecurity guy than a physical security guy. Here everyone earns about the same, so I have to hire a junior cyber person and train him.”

Finding the various skill sets in a single person is rare. According to the vice president of enterprise risk management and global security for an international tech company: “We have not found a skill set or competency in one individual that addresses the three buckets—cyber, physical, and BC (business continuity). The downside is that this talent costs money. So we tackle these risks as a team. The upside is you have more eyes on it.”

Despite the constant drumbeat that convergence reduces costs, that conclusion isn’t borne out by the numbers. Only 7 percent of security executives from converged organization cite cost savings as a primary benefit of convergence. In fact, 6 percent say that convergence actually added cost.

Oversight of a converged function. One of the fears of convergence is the loss of jobs, influence, or authority by, say, physical security and business continuity if the CISO gets tapped to lead the combined function. Who ends up leading the converged effort is often based on culture, personality, relationships, or even happenstance. A minority of organizations report to a chief risk officer or another executive who owns the entire organizational risk palette, but at the rest, the organizational arrangement may pit security leaders and staff against one another.

One European telecommunications company has faced challenges with battles for primacy. “The main barriers to convergence were turf and silo issues,” says the vice president of group security. “Everyone wanted to safeguard his responsibilities, his people, his budget, his prestige, and his importance to the company.”

Collaboration Without Convergence

The study found that even nonconverged companies believe there are major benefits to convergence. Almost 80 percent of nonconverged organizations acknowledge that convergence would strengthen their overall security function.

The key observation, supported by interviews, is that convergence or integration needs to be customized to fit the needs and demands of individual organizations within specific lines of business. There is no one model that works for everyone.

Take, for example, the operation of a major U.S. financial services firm. The CISO heads cybersecurity and reports to the CIO. He has “a limited relationship” with physical security, which is headed by a director of security who reports to human resources. Says the CISO: “We have meetings once a month to discuss everything from access to potential systems integration to overlap in our security centers. We coordinate access to our buildings. We need physical security to understand the controls we have in place for things like data centers. We also collaborate on execution because we need to know if we have people on site.”

At this financial services firm, where data security is essential, business continuity planning reports to the CISO. That’s where there is currently some convergence but not total convergence. So far, customization works for this firm. “[We have] no current plans for convergence, but I stated it is something I want to do in three to five years,” the CISO says.

Nebulous plans or inchoate ideas for future integration of the three functions essentially summarizes the state of security convergence today. The ASIS Foundation data and interviews show that the rewards are there, but doubts persist, and organizational obstacles remain. Perhaps Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s observation that “Everything that rises must converge” does apply to security—only the security function hasn’t yet risen high enough in the corporate hierarchy.

Michael A. Gips, CPP, is a member of the ASIS Foundation Research Committee and former executive at ASIS International. This article is based on the ASIS Foundation report The State of Security Convergence in the United States, Europe, and India—sponsored by AlertEnterprise—with principal author David Beck and contributor Beth McFarland, ASIS Foundation Director.