The Fraudians Slip In

Fraud is thriving these days, and many of its practitioners have acquired daunting levels of skill and ingenuity for reading the current operational environment, finding weak links, and adjusting their methods to maximize the likelihood of successful scams, experts say.

"They are as skilled in committing these frauds as any skilled person is in any field of endeavor," says Alan Brill, a director with Kroll's cybersecurity and investigations practice. "They are criminals, but you have to respect the level of skill that they have, to know what you are up against."

This fraudulent activity is affecting more and more companies, according to a new study. About two-thirds of U.S. companies reported an increase in fraud attempts over the past 12 months, according to The Fifth Annual Fraud Report: A New Landscape Emerges, a study issued by IDology, an Atlanta-based identity verification firm. Last year, fewer than half (42 percent) of U.S. companies reported such a rise.

And it's not only the sheer number of fraud attempts that is changing. Methods used in perpetrating fraud are evolving, too.

"The biggest challenge faced by businesses in the fight against fraud has been the continually shifting tactics used by fraudsters," reads the study, which finds that 71 percent of organizations cite "shifting fraud tactics" as their greatest challenge.

Use of fraudulent credit, debit, and prepaid cards is still the most prevalent type, with 65 percent of respondents saying that it is the most common method in their industry. However, there are signs that it is starting to decrease. That 65 percent figure is actually down from the 73 percent of respondents who cited that fraud type in last year's survey.

According to the report, the reason behind this decrease is the widespread adoption of EMV chip cards, which have reduced point-of-sale fraud. With chips making it harder to commit this type of fraud, more criminals are shifting to an online environment, where the customer is not present. "They will try to find the path of least resistance," IDology CEO John Dancu says.

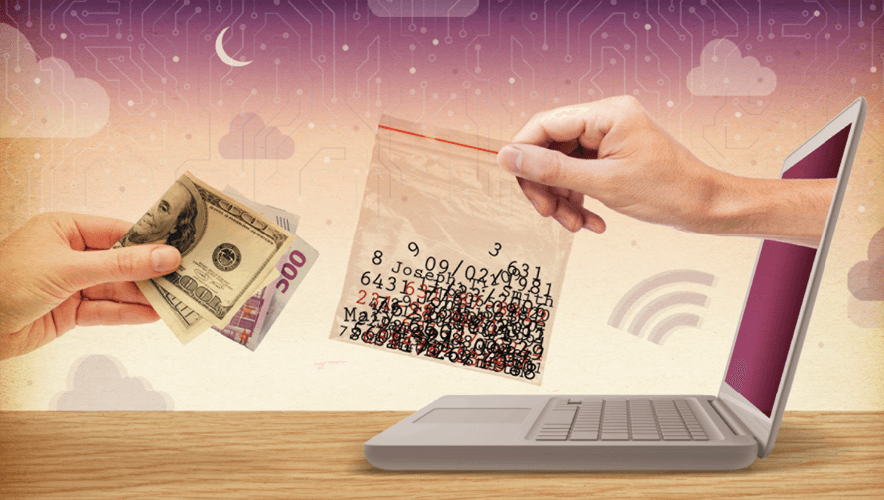

There's another driving factor behind the shifts in the fraud landscape, and it has to do with how nimbly the fraudsters share knowledge. "They are really good at communicating among themselves," Dancu says. Sometimes, they will discuss methods on the Dark Web; this keeps them situationally aware and helps them change methods if necessary.

Some are also not shy with expressing pride of craft. "When they find a weak link, they are happy to tell everybody else about it," Dancu explains. "If you're on the Dark Web or their other forums, you can see the interactions and the professional enjoyment that they have in letting other people know what they have discovered. It's about being The Man."

Those dark websites and other places where fraudsters sell information and data are pretty sophisticated enterprises, Brill says. "There is a comradeship among people who do this. They do meet at the marketplaces, and these marketplaces don't look that different from eBay, with vendors getting rated by people that buy from them," he explains. Some vendors even offer BOGO specials, he adds.

As is true with most fields of endeavor, this increased professionalization brings about more specialization. So, some fraudsters specialize in malware, some in the monetization or selling of breached data, and some in "social engineering"—knowing how to get to the right entry point to access information, Brill explains.

He offered the following example of a social engineering specialist. These days, many banks frequently advertise how effective they are in protecting customers against fraud. In this environment, it may then be no surprise if one day you get a phone call from Visa security, with the caller informing you that your card was just charged with suspicious activity—$300 from an adults-only emporium in Las Vegas. Horrified, you deny the charge and ask for it to be cancelled, and so you gladly give your card information, Social Security number, and date of birth when the caller asks if they can verify you as the cardholder.

But what you might not realize is that you just handed over your information to a criminal posing as security. This type of thief takes advantage of the expectations created by frequent bank commercials that promote their quick security operations. "In effect, you have been primed for a social engineering hit," Brill says.

Although the study finds that customer-present credit card fraud may be decreasing, it also finds that synthetic identity fraud (SIF) is a growing problem. In an SIF scam, a combination of real and fabricated identity information is often used to create a new identity. Thirty-one percent of businesses in the report say SIF has increased, and 58 percent are "extremely" or "very" worried about it. Helping to drive this problem is the recent flood of major data breaches, which gives criminals more identity data to use.

In Kroll's investigations practice, Brill is seeing a big increase in the following type of case. A fraudster obtains the Social Security number of a young child in the aftermath of a data breach, then uses it with other information to open a few credit accounts, including one or more credit cards.

The scammer then exploits the accounts for years, with charges that are never repaid and lapse into default. Finally, the young child becomes old enough to apply for a credit card, or a lease on an apartment, and is surprised to find out that his or her credit rating is abysmal.

Marcus Christian, an attorney in Mayer Brown's White Collar Defense & Compliance group, also sees SIF as an increasing problem. Christian, a former prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Florida, has heard reports that some of the criminal organizations in South Florida have been shifting away from selling narcotics and toward identity scams. "The money is as good as, if not better than, the drug trade," he says. In addition, it is often perceived as a less dangerous practice, and through connections in local school systems and banks, these criminals can obtain stolen data, he adds.

The second-most cited type of fraud in the report—first-party or friendly fraud—is also on the rise, with 51 percent of respondents saying they have been a victim of it, nearly double the percentage (26 percent) of respondents who cited it in last year's survey.

First-party or friendly fraud generally describes fraud committed by individuals using their own accounts. These types of fraudsters might make an online purchase and then dispute the charge after the merchandise has been received, or they might open credit card accounts with the intention of maximizing charges and then lapsing into default to avoid full repayment.

One reason first-party fraud is increasing, the study finds, is that it is difficult to foil; it is hard to disprove false claims that ordered merchandise was never received, for example. However, experts say that big data applications hold some potential in this area as a security tool, because they can be used to recognize patterns of excessive refund requests and other telling information.

Finally, Dorcu says that another cause for optimism in the fight against fraud is that an increasing number of companies are realizing the importance of working together. Fraud is a serious issue for companies regardless of industry, and since the perpetrators are sharing information and strategies, those fighting fraud need to do the same, under a consortium mindset.

"Getting connected and talking with peers is really an important part of solving the problem," Dorcu says. "Be flexible, be collaborative, and be open-minded to what's going on out there."