Responding to San Bernardino

Fourteen people were shot and killed during a holiday party at the Inland Regional Center (IRC) in San Bernardino, California, on December 2, 2015. The incident was eventually classified as an act of terrorism, because the shooters had ties to the Islamic State.

Employees of the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health had gathered for an employee training and luncheon in the morning hours when the male shooter, who was also employed by the county, and his wife opened fire. In addition to the 14 killed, 22 county health workers were injured, and hundreds were evacuated from the IRC.

Assistant Chief of Police Eric McBride tells Security Management that his department was immediately reliant on outside organizations for help in the aftermath. “We had several hundred people, including victims that weren’t wounded, from the scene, and witnesses that needed to be transported to an offsite location so they could be interviewed,” he says.

The department has a longstanding relationship with a local church that can seat several thousand people in its worship area. “We’ve used their facility in the past for training…so we were able to call them up and were able to have people transported by buses to that church,” McBride says. “It was a large location where they could be secured, away from prying eyes.”

The school district’s emergency manager, a sworn police officer, arrived at the IRC and began coordinating school bus routes to transport people to the church for interviews with law enforcement. The police department also solicited the help of Omnitrans, the San Bernardino regional bus service, for transport. “Everybody that survived was transported from the scene within about 45 minutes of the incident,” he says.

Conducting witness interviews as soon as possible is paramount to an investigation, McBride explains, so the quick coordination helped greatly in the overall response. It was also beneficial to have the witnesses spread out in a large facility. “It’s important to somewhat isolate [witnesses] so they don’t hear each other provide their statements,” he says. “Their statements need to be pure, and not be influenced by what someone else says.”

McBride notes that in the chaos of an active shooter event, friends and family are understandably anxious to locate their loved ones. However, many survivors leave their cellphones behind and are unable to communicate their safety. Law enforcement disseminated information through social media that status updates on survivors and victims would be given by the police only at a nearby community recreational center. This kept people and media from swarming the church after word had gotten out that interviews were taking place there.

The San Bernardino suspects were still being actively pursued by police in the hours after the shooting. This element of uncertainty among the public made communication even more critical for the department, McBride explains.

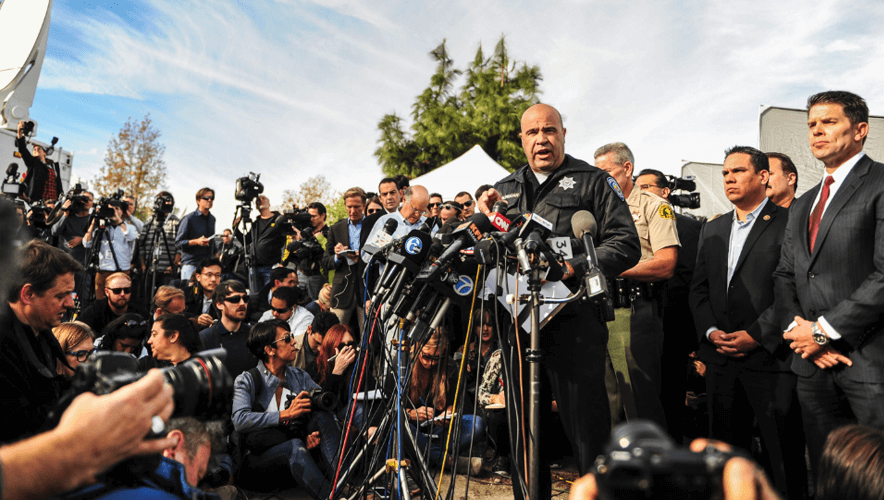

The police set up a media staging area outside a Hilton Garden Inn a few miles south of the IRC, and kept a public information officer there throughout the day to answer any questions that came up between the regular press conferences.

The department also kept up with the latest news so that they were prepared for anything.

“Before each press conference, we had people who were monitoring social media and news accounts to see what information was being printed, and what people were saying,” McBride says, “so we could anticipate before each press conference what the types of questions would be.”

He adds that the police chief’s Twitter account played a primary role in disseminating information. If law enforcement had new information to release but not enough to justify staging a press conference, they would release it on the social site. “So the media knew they would only get information from us through his Twitter account,” if it wasn’t through a press conference, he notes.

Finally, McBride says the San Bernardino police worked with the local sheriff’s department, law enforcement from nearby municipalities, and outside agencies, including the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, to coordinate response efforts. “It was important to have those relationships beforehand with our city partners and other agencies within the city,” McBride notes. “Everyone worked well together, no one got out in front of each other, and we coordinated everything very well.”