On the Trail of Stolen Artwork

Isabella Stewart Gardner was a remarkable woman. Born in New York City in 1840, she was educated abroad before being introduced in Paris to the man who would eventually become her husband: John “Jack” Lowell Gardner, Jr., whose family was involved in the East Indies trading business.

The couple moved to Boston into a house her father purchased for her as a wedding present, where they later had a son—Jackie. But when he was just two years old, Jackie caught pneumonia and died, causing Gardner to sink into a deep depression. To help rouse her spirits, Jack took her on a trip to northern Europe and Russia.

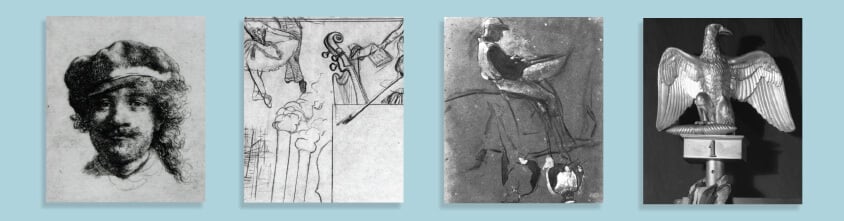

These international trips would become a regular occurrence for Gardner and her husband. They would nourish Gardner’s love of the arts and she would use them to acquire a vast collection of masterpieces, including numerous Rembrandts like his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, A Lady and Gentleman in Black, Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, and The Concert. She also bought Edgar Degas’ Study for the Programme charcoals, Procession on a Road Near Florence, Leaving the Paddock, and Three Mounted Jockeys; Govaert Flinck’s Landscape with an Obelisk; Édouard Manet’s Chez Tortoni; Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert; Antoine-Denis Chaudet’s Eagle Finial; and a 12th century BC Chinese bronze gu vessel.

After her husband died, Gardner continued with their plan to purchase land and build a museum to house their extensive art collection. Willard T. Sears designed the museum in the Fens neighborhood of Boston, and Gardner opened it to the public in February 1903.

When she died in 1924, Gardner left the museum “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever,” according to her will. But this came with a stipulation: nothing in the galleries could be changed; no items could be sold or acquired for the collection. The museum must remain exactly as she left it when she died.

And it did until the middle of the night on 18 March 1990 when two men disguised as Boston police officers approached a side employee entrance to the museum. They pushed the door buzzer, said they were responding to a report of a disturbance, and asked to be let inside.

A security guard on duty broke protocol and let the men in. The imposters overtook the two guards on duty, handcuffed them, and tied them up in the basement of the museum. Eighty-one minutes later, the thieves left the museum with the 13 works of art mentioned above—together valued at roughly $500 million.

The theft remains the largest unsolved property crime ever committed in the United States. And because of the stipulations of Gardner’s will, the frames where the pieces should be displayed in the museum remain empty—a constant reminder of their loss.

“It’s sort of the perfect storm of loss in that the pieces are priceless and irreplaceable,” says Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Director of Security Anthony Amore. “Nothing else can be displayed in those places, and they can never be replaced.”

Art crime is often romanticized by Hollywood. A multi-millionaire steals a Monet and falls in love with an insurance investigator assigned to the case, à la The Thomas Crown Affair. A group of thieves band together to steal a Fabergé egg to one-up another criminal, as in Ocean’s 12. There are countless other stories that paint these thefts in a rosy light, but the actual crimes involving cultural property represent much more than the theft or destruction of an object from an individual collection.

“What if when the Mona Lisa was stolen earlier in the 20th century, the French brushed it off and just said, ‘Oh, it’s a painting.’ Or if the Egyptians didn’t care about preserving their cultural property? Look at what you’re robbing future generations of,” says Tim Carpenter, manager of the FBI’s Art Crime Team. “We see it as our duty to protect our cultural heritage. It’s important to be able to pass this along to our children and to future generations.”

The FBI’s Art Crime Team is made up of roughly 20 agents who have an appreciation for cultural property and protecting art, Carpenter says. Their job is to step in to take the lead—or assist the Bureau’s roughly agents in 56 field offices on cultural properties crime investigations.

When selecting a new art crime agent, “What I look for first is are they a good investigator? Do they understand why we’re doing it? Do they have a passion for cultural property?” he adds. “I’m not as concerned with their pedigree. We have to understand why we work these types of cases.”

The agents on the team undergo training on how to safely handle artifacts, along with annual sustainment training in different regions of the United States with institutions that can teach them about trends and techniques.

“One year we might be focused on painting forgeries, so we got to institutions and learn from them—we look at their conservation activities,” Carpenter explains. “Or we’re looking at textiles, Civil War memorabilia; we try to get as broad a range of training as possible.”

Each agent on the team is assigned an international and U.S. region to work with partners on cases involving thefts, forgeries and fakes, antiquities trafficking, and money laundering.

“We have to prioritize the work that we’re doing to maximize our resources,” Carpenter says. “In 2014, the threat at the time was conflict area antiquities trafficking—that was a big concern for us and the U.S. government. Today, we’re more concerned about money laundering in the art market.”

For instance, a common money laundering scheme could involve a criminal who has $10 million in cash. His ability to convert it into a day-to-day commodity would be limited because of anti-money laundering regulations, so he might look to purchase a painting from an auction house with that money.

“Art is largely unregulated and can freely move across borders,” Carpenter says. “If I convert [the cash] into art, I can turn it around and sell it at auction. It’s a fairly easy, low-risk way to move wealth.”

The Art Crime Team has seen an uptick in these cases and is highly involved in investigating them because of the large consumer market of dealers and auction houses for art and illicit cultural property in the United States. The team also works with international partners on these cases—especially in Italy, which has one of the largest and most robust art crimes programs in the world with roughly 300 investigators, Carpenter adds.

This shows how art crime is continuously evolving and is not just limited to thefts of art from institutions. Carpenter says that, surprisingly, only 30 to 35 percent of the cases the team investigates are stolen works. Most of these are taken by insiders with access to a museum’s collection storage; they typically steal lesser known pieces that might be easier to sell on the open market.

“Bob Whitman, an old friend and colleague of mine, used to say ‘It’s not stealing the painting, but selling it. That’s the hard part,’” Carpenter says. “That speaks to why these thefts of high-end pieces are really rare. It’s too hard to sell them because they’re known stolen pieces. Even on the black market, you’re going to get pennies on the dollar for it.”

None of the art that was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has been recovered. In 2017, a West Virginia man was indicted for a scheme to sell some of the stolen paintings on Craigslist.

The U.S. Department of Justice said that the man, Todd Andrew Desper, acting under the pseudonym Mordokwan, “solicited foreign buyers for both the Storm on the Sea of Galilee and The Concert on Craigslist in a number of foreign cities, including Venice and London,” according to a press release. The man “directed interested buyers to create an encrypted email account to communicate with him.”

Unfortunately for Desper, one of the individuals who answered his ad and communicated with him was Amore—the security director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner—who alerted the FBI.

Desper was arrested, pled guilty, and later admitted that he had no knowledge of where the actual pieces stolen from the collection were located. But theories abound about where they might actually be. Books have been written, a podcast series was devoted to the topic, and the art community continues to speculate where they are, such as in someone’s attic, says Robert Carotenuto, CPP, PCI, PSP, director of security at The Shed in New York City.

“For all of us directors of security, there’s always the determination that those works of art will somehow be recovered,” says Carotenuto, who is the former chair of the ASIS International Cultural Properties Council. “It’s no longer likely about the tips—it’s that someone is going to rummage through an attic and find it.”

This was the case with a Marc Chagall painting that was stolen and missing for almost 30 years before being recovered in 2018 in the attic of a man allegedly connected to Bulgarian organized crime.

The FBI Art Crime Team recovered Othello and Desdemona, which was taken from Ernest and Rose Heller’s apartment in 1988 by an insider who was stealing from the building’s tenants when they were out of town.

Other theories include that Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum paintings are in someone’s private collection, destroyed, or lost. The reward for information that leads to the return of the stolen Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum paintings is now $10 million.

“The fact that no one has claimed that money, it would seem to me that no one knows where they really are,” Carotenuto says.

Despite the lack of public developments, the FBI and the museum continue to investigate the case and are open to receiving facts to further their efforts, Amore says.

“The theft is unusual—there has never been a theft in the history of the world that comes close. It’s impossible to ignore it,” he adds. “When something of this enormity has happened, you can’t just turn the page.”

This is one of the reasons why the museum maintains a page on its website devoted to the theft of the pieces and regularly does public outreach and media outreach to raise awareness. The FBI Citizens Academy also presents information about the theft in its courses, and Amore maintains a good relationship with the FBI lead on the case, Geoff Kelly.

Ultimately, it’s all in the hope of someday returning the paintings to their rightful places in Isabella Stewart Gardner’s collection.

“The paintings must be recovered, and they must be put back into the spots that Isabella Stewart Gardner assigned them,” Amore says. “They have to be recovered and displayed. She gave the museum to the public for its enjoyment and entertainment forever.”

If you have information about the whereabouts of the paintings stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, you can contact the FBI at 1.800.CALL.FBI or the Museum Head of Security and Chief Investigator Anthony Amore at [email protected].

Megan Gates is senior editor at Security Management. Connect with her at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @mgngates.