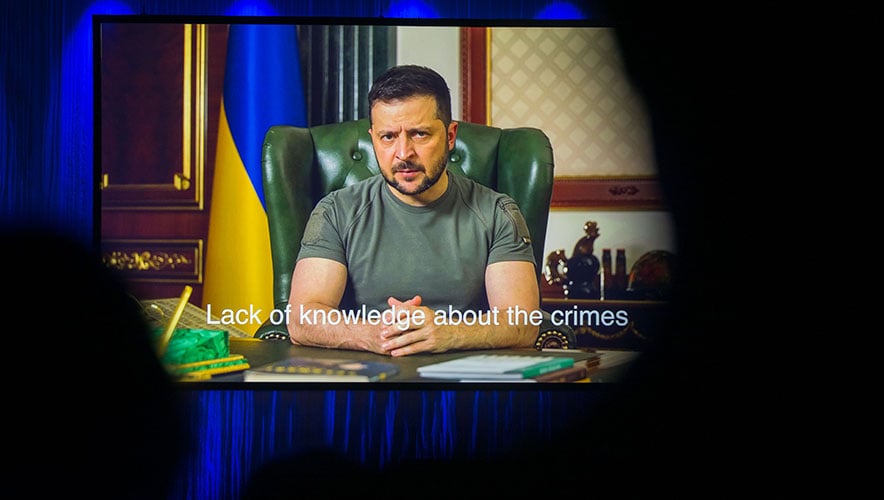

Ukraine Update: Zelensky Says Russia Plans to Destroy Dam

Earlier this week, Russian authorities began an evacuation of more than 50,000 people from the Kherson area in Southern Ukraine. As part of the justification, Russia said Ukraine planned to destroy the Kakhovka Dam. In his nightly radio address on 20 October, Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky said Ukraine has uncovered evidence that Russia has mined the dam and intends to blow it up and blame Ukraine in a false flag attack.

President Zelensky accuses Russia of plot to blow up dam in southern Ukraine https://t.co/BGfdf9ojuv

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) October 21, 2022

Destruction of the dam would be a devastating disaster for the Kherson region of Ukraine, which is about 70 miles north of Crimea. The Institute for the Study of War said the reservoir holds approximately 18 million cubic meters and the ensuing wall of water would rapidly flood Kherson and surrounding towns, affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

In its report, the institute said Russia has been circulating maps that show the likely flood path and that Russia appeared to be “setting information conditions for Russian forces to blow the dam after they withdraw from western Kherson Oblast and accuse Ukrainian forces of flooding the Dnipro River and surrounding settlements, partially in an attempt to cover their retreat.”

Kherson is the latest strategic city that Russia may be forced to relinquish as Ukraine continues to retake territory Russia gained in the early phases of the war. With a prewar population of 284,000, Kherson is the largest city that Russia captured since it invaded Ukraine. It is strategically important because of its industry and major river port, and because of its proximity to Crimea, which has been under Russian control since 2014.

Destroying the dam would be a further blow to Ukraine’s electrical infrastructure. In addition to providing water to parts of the Crimean Peninsula, the dam is a hydroelectric power source and is the water supply for the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant.

Since 10 October, Russia has intensified the targeting of infrastructure throughout Ukraine with artillery, missiles, and drone attacks, focusing particularly on energy infrastructure. According to The Washington Post, one-third of Ukraine’s transformer stations have been destroyed, causing major disruptions to the country’s ability to transmit electricity from power plants to consumers. Ukrainian power companies have initiated rolling blackouts and the governor of Kyiv asked residents in the capital region to unplug appliances from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. Among Ukrainian officials, the attacks are “raising fears of a winter without, power, heat, or hot water.”

Energy fallout from the war goes beyond Ukraine. The European Union held meetings this week to address the wider energy crisis the war creates throughout the continent. Some in the bloc are pushing for gas price caps to counter Russia’s strategy to restrict gas supplies whenever it feels it is strategically expedient to do so. EU leaders, however, could not reach an agreement.

“There is a strong and unanimously shared determination to act together, as Europeans, to achieve three goals: lowering prices, ensuring security of supply, and continuing to work to reduce demand,” said meeting host Charles Michel, the EU Council president, while announcing the talks would continue next week.

In other news involving the war in Ukraine, Russia declared martial law in the regions it says it has annexed and the use of Iranian weaponry by Russia has stoked a backlash against Iran.

The declaration of martial law came from Russian President Vladimir Putin came on 19 October. It’s not clear how the declaration will change much in the Russian-held areas of Ukraine. As The New York Times reported, “As a practical matter, Moscow has only tenuous control of the eastern Ukrainian regions where it imposed martial law. …In Ukraine, the martial law order will allow the authorities to impose curfews, seize property, forcibly resettle residents, imprison undocumented immigrants, establish checkpoints, and detain people for up to 30 days.”

However, a key part of the declaration is signified in Putin’s announcement: “I signed a decree on the introduction of martial law in these four constituent entities of the Russian. In addition, in the current situation, I consider it necessary to give additional powers to the leaders of all Russian regions.” (Emphasis added.)

An Associated Press (AP) analysis of the decree noted “Putin could be laying groundwork to extend these restrictive measures throughout Russia. A clause in the decree allows measures envisaged by martial law to be imposed in any Russian region ‘when necessary.’ What’s more, officials in multiple Russian regions rushed to assure the population after Putin’s announcement that they’re not planning to impose additional measures.”

The analysis noted that in the 1970s and 1980s, between 10,000 and 15,000 Soviet Union troops died in an 11-year conflict in Afghanistan, compared to conservative estimates of 50,000 killed in the eight months of conflict in Ukraine.

The move is a possible consequence of a Russian public that is turning against the war. Putin mobilized reservists last month, an action that caused several protests throughout the country and resulted in thousands of draft-eligible men to attempt to flee the country.

One Russian affairs expert, Tatiana Stonovaya, told The New York Times, “Putin has to prepare the country for much harder times, and he needs to mobilize resources.” Another expert, Abbas Gallyamov, said, “In general, all this looks not so much like a struggle with an external enemy, as much as an attempt to prevent the ripening revolution within the country.”

Media have dubbed the Iranian drones Russia has been using this week as “Kamikaze” drones because they are laden with explosives and flown directly into targets. U.S. intelligence said Iranian troops are in Crimea to teach Russians how to operate the drones. Iran denies it is aiding Russia. One fear is the drones are just the start, and that more advanced weaponry, such as ballistic missiles with a much higher explosive yield than the drones, could be deployed. There is also concern about what deeper ties between Iran and Russia might mean outside of the Ukrainian context.

“There could be implications for the future of the moribund nuclear agreement between the international community and Tehran,” the BBC analysis found. “Furthermore, the delicate balance of forces in Syria could be altered with significant consequences for Israel and, in turn, for its relationship with Moscow. Clearly both Russia and Iran need friends. They are both isolated and embattled.”

Security Management examined the expanded use of consumer drones from early in the conflict. The New York Times looked at the growing use of drones in the Ukrainian conflict and what it means for future war and conflict. “It…gives a taste of what is to come as the technology gets more advanced and more widespread—just as missiles went from novel and not all that effective to the norm of war, the same will happen with swarms of armed drones,” military tactics expert Peter Singer told the Times. “As recently as a few months ago, there was still a debate among both about whether drones would be effective in a major conventional war, as opposed to just counterterrorism and insurgency,” he said. “That debate is now utterly over.”

Despite the ravages of war, a Gallup poll of Ukrainians from early September shows the country remains unified in its opposition to Russia. Eighty-four percent approve of the job Zelensky is doing, and 94 percent say they are confident in their armed forces. The support is widespread throughout the country, ranging from a low of 78 percent approval of Zelensky in Eastern Ukraine (the area closest to Russia) and 91 percent in the center of the country.