Putting Multi-Option Active Assailant Response to the Test

Print Issue: October 2019

Following almost every major mass shooting in the United States, law enforcement officials methodically evaluate and repeatedly try to improve their response.

Law enforcement demonstrated this evolution after the Columbine High School shooting in 1999 that killed 13 people. Following the shooting, police changed their methodology of waiting outside the facility for the SWAT team to engage the shooter to having small units—often consisting of the first four officers to arrive on the scene—engage with the active shooter.

After 32 students and faculty members were killed in the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007, police response tactics changed again—moving from small units to solo engagement of the shooter. This response was further improved upon when law enforcement began engaging shooters and bounding overwatch to detect explosive devices following the San Bernardino, California, shooting in 2015 that left 14 people dead.

Most recently, law enforcement began stressing the importance of a unified command to assist in saving lives after a gunman opened fire at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, killing 49 people.

The trend to attempt to fix responses after failure has been no different for civilian responses to active shooters and, most notability, for the single-option, traditional lockdown response, which recommends individuals get into a room, lock the door, turn off the lights, move away from the door and windows, hide behind available objects, stay quiet, and wait for the police to arrive.

For example, after the failure of traditional lockdown at Columbine High School, the condition that everyone needed to be in a room for lockdowns to work was added to the response. When traditional lockdown failed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, the response recognized that the placement of the locks on the door was an important factor that must be considered. Most recently, in the aftermath of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, the failure of traditional lockdown is being attributed by some to a lack of lines on the floor that identify the hard corner where people can hide, and new responses are evolving to include the proper marking of these corners. However, none of these solutions make allowances for the fluidity of active shooter events nor do they recognize the decision-making capabilities possessed by those who find themselves in the midst of such an event.

In 2000, when Greg Crane developed a multi-option response for active shooter events, he followed a well-recognized model pioneered by the fire services from more than a century earlier. Fire services realized that no one response was appropriate for all incidents involving a fire. Thus, training options were developed based on fire’s ability to move and the understanding that one or more of the responses might not be available or appropriate for the circumstances. Based on this knowledge, Crane saw a need that was not being met by the single-option traditional lockdown response in active shooter events and surmised the response was increasing casualties. As a result, he developed ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate) Training.

In the same way fire services trained and provided options for individuals to use based on proximity to the fire, Crane created a multi-option response that used information based on the location of the shooter to determine how individuals may want to respond. For example, just as fire safety instructs individuals—if possible—to leave a facility if it is on fire, Crane’s ALICE Training also provides the option to evacuate a building—if able to—in an active shooter incident.

If individuals are unable to evacuate in a fire, fire officials inform people to get low to the ground, close the door, and put something under the door to create a barricade between themselves and the fire and smoke. ALICE Training also recognizes there are instances when evacuation is not possible and suggests people lockdown and barricade with available environmental objects—desks, chairs, or tables—to prevent contact with the active shooter.

Finally, fire services recognize that someone may catch on fire and recommend people Stop, Drop, and Roll, countering the fire. Crane similarly acknowledges that in active shooter incidents someone may come face-to-face with a gunman. ALICE Training addresses this by having an option to counter the gunman by throwing objects or swarming the shooter to survive.

In both fire safety and ALICE Training, the dynamics and ever-changing nature of the incident are recognized. By providing individuals with multiple options, neither the fire service nor ALICE would guarantee that there will be no injuries and everyone will survive. Rather, giving people options to choose their response instills knowledge and confidence and, arguably, may increase their likelihood of survival.

While there have been two competing paradigms to civilian active shooter responses for almost 20 years, no empirically sound studies were conducted on the effectiveness of either the single-option, traditional lockdown or multi-option responses to active shooters. Some individuals assert that the single-option, traditional lockdown is well researched and a proven best practice. But there is no solid empirical evidence to validate these claims, and there is anecdotal evidence to suggest otherwise.

This dialogue changed in December 2018 when the authors’ study “One Size Does Not Fit All: Traditional Lockdown Versus Multi-Option Responses to School Shootings” was published in the Journal of School Violence. The article, to the authors’ knowledge, is the first peer-reviewed study to examine the differences in time to resolution and survivability between traditional lockdown and multi-option responses to active shooter incidents.

Using live simulations with AirSoft guns in both classrooms and large open areas such as cafeterias, libraries, and hallways, the study ethically and safely recreated a mass shooting incident. In 13 sites across the United States, 326 individuals attending a two-day ALICE Instructor course voluntarily consented to be part of the study. These simulations were already a component of the ALICE training course. However, no one had previously surveyed individuals about their experiences and feelings during these drills.

Before any simulations were conducted, participants filled out a survey to collect their basic demographic information and feelings about mass shootings. Then, after each simulation, they were asked to report the number of times they were shot and the actions they took in response to the shooting.

When all simulations were finished, participants completed a final post-test survey. To mitigate potential confirmation bias of the researchers, all participants self-reported their answers on each of the surveys. Additionally, the individuals who were chosen to be the gunman in each simulation were not affiliated with nor invested in the ALICE Training Institute.

For each simulation, the gunman was armed with two AirSoft guns and stopped shooting when one of the following occurred: five minutes elapsed, which was based on the fact that 70 percent of active shooting incidents ended in five minutes or less; the gunman ran out of ammunition, similar to what occurred in the shooting at Marshall County High School in 2018; participants incapacitated the gunman; all participants evacuated the area; or all participants successfully barricaded and the gunman was unable to engage further targets.

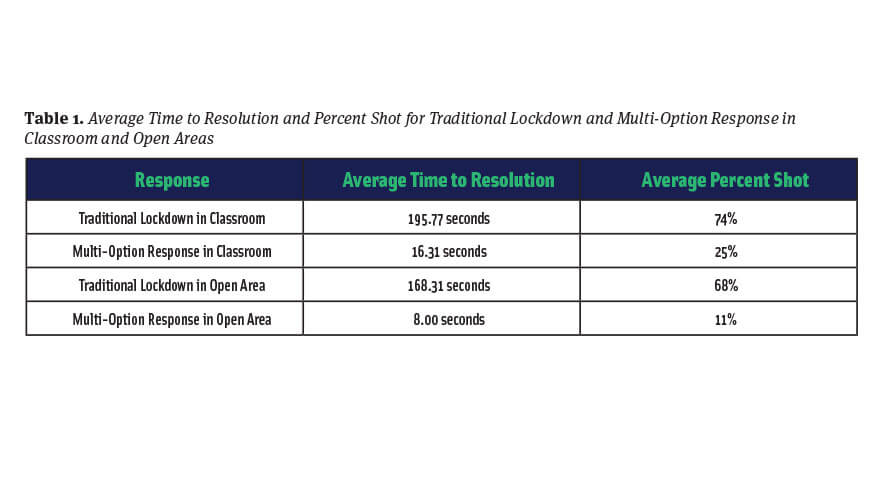

The study results showed statistically significant decreases in the percent of individuals shot using the multi-option response over traditional lockdown. Across the 13 sites, 74 percent of participants who used traditional lockdown in a classroom were shot. But only 25 percent of participants who used the multi-option response were shot. When traditional lockdown was used in a large open area, 68 percent of the subjects were shot; this dropped to 11 percent when multi-option responses were used. Furthermore, no demographic or situational variable gathered in the study—sex, age, occupation, SWAT training of the gunman, or use of counter technique—significantly predicted being shot, suggesting it was use of the multi-option response instead of traditional lockdown that resulted in fewer people being shot.

Additionally, the time to resolution for both the classroom and large open area simulations significantly decreased when using the multi-option response instead of traditional lockdown (see Table 1).

These results could have a significant influence on training and policy. A 2018 compilation of data on mass shootings, financed by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), found that current or former students are the assailants in nine out of 10 school shootings. Thus, the vast majority of school shootings are insider attacks by individuals who know where everyone is in a facility. Single-option, traditional lockdown responses that instruct everyone to only hide in an active shooter situation are high-risk, high-liability propositions that ignore the fluidity and ever-changing nature of these events.

Jillian Peterson and James Densley, the two criminologists who developed the NIJ database on mass shooters, wrote in an article for The Conversation that “…current strategies are inadequate. If the shooter is most likely a student in the school, lockdown drills only show potential perpetrators the school’s planned response, which can be used to increase casualties.” Thus, the failure of traditional lockdown is its reliance on a one-size-fits-all approach.

Decisions and policies should be based on and driven by existing data, rather than emotional appeals to do something to keep students, staff, faculty, and other civilians safe. Competing approaches should be ethically tested and validated. But the limited evidence suggests multi-option responses that consider the dynamics of an active shooter incident, rather than single-option, traditional lockdown, have the potential to increase the survivability of those who are faced with such an encounter.

These same arguments can apply to commerce settings, which make up the largest percentage (42 percent) of active shooter events according to the FBI’s report on active shooting incidents in the United States. In 58 percent of active shooter incidents between 2000 and 2017, the gunman was an employee, a former employee, or related to someone inside the facility—meaning the individual had insider knowledge of the location.

Many employees and patrons, however, are only trained in traditional lockdown, which instructs them to sit on the floor, be quiet, not move, and wait for the police to arrive to the scene. Once again, this tactic is the single-option, traditional lockdown response that expects the shooter to be unaware of which rooms have people in them—which is not the case in more than half of these incidents.

The failure of lockdown drills in locations such as Sandy Hook Elementary and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High Schools, both of which conducted traditional lockdown training shortly before their respective incidents, draws an unflattering light on this type of response to active shooters. Arguments about security measures, arming teachers, the presence or absence of school resource officers, automatic lockdown procedures, door locks, and even where tape should be on the floors for people to hide behind have gripped the national discourse on what to do in response to such events. What is consistent, however, is that most of the focus is placed on the failure to properly implement lockdown or the application failure of the lockdown (blaming the people) rather than on the fact that the single-option, traditional lockdown failed (blaming the tactic).

In light of new research, it is apparent that the tendency to blame people is misguided and a serious examination of the tactics we use to train civilians to survive an active shooter event is necessary.

One argument for retaining the single-option traditional lockdown response is that it takes very little time to train people. Individuals are told to turn off the lights, lock and move away from doors, hide under or behind objects, and to remain quiet. Individuals are instructed to pretend they are not there and to wait for the police to respond, even though they are likely in a building where people are in almost every room. Add to the equation an insider threat—a person who works or goes to school in that building, who already knows where people are most likely hiding—and the effectiveness of this response breaks down with life-threatening results.

It is common knowledge that for training to be effective, one must prepare for the event as if it is going to happen—in a realistic and safe way. Just as people have practiced from a young age how to respond to fires, they should practice how to respond to an active shooter. The trainers must be safety-conscious professionals. In addition, for active shooters, the response should not require any fine motor skills of participants such as weapons takeaways or fighting tactics because these skills decrease in periods of high stress.

Training should be conducted with everyone, be age-appropriate, and be presented in a way that increases feelings of empowerment and confidence, rather than feelings of fear and anxiety—just as it is done in other crisis situations like fire, tornado, and Stranger Danger. It should be kinesthetic with every option being trained. Finally, the training must be consistently delivered, practiced, and conducted on a continual basis. It should also parallel that of fire safety, where schools are required to conduct fire drills on a routine basis.

While anecdotal evidence and the limited empirical research show that when people are trained in multi-option responses lives can potentially be saved, not everyone supports this type of training.

Unfortunately, because of the frequent failure of traditional lockdown tactics and the large numbers of casualties, a general fear of active threats has arisen. As a result, some are suggesting drills could be contributing to this fear and that they should not be conducted. However, there are many instances where training and drills have saved lives.

Rather than focusing on failed lockdown incidents, the focus should be shifted to locations where multi-option responses succeeded. Noblesville, Indiana; Mattoon, Illinois; and West Liberty-Salem, Ohio, are all locations where multi-option responses saved lives. However, very few people have heard of these incidents. At both Noblesville West Middle School and Mattoon High School, a teacher subdued the gunman; no one was killed in either incident with three injured between the two schools. At West Liberty-Salem High School, students and teachers barricaded their classrooms and evacuated the building. One student was injured. These success stories get little notoriety from the media and are typically only known by the professionals in the field.

And, while there are no guarantees that all lives will be saved, multi-option response use from anecdotal evidence and the limited empirical evidence suggests that this response could reduce the amount of time a threat is active in a building and mitigate the number of casualties.

In this regard, more methodologically rigorous, peer-reviewed research is needed. Studies that evaluate the psychological impact that drills have on their participants, including children, should be conducted. Utilizing evidence-based civilian active shooter responses should be a top priority. Future lives depend on it.

Dr. Cheryl Lero Jonson is an associate professor of criminal justice at Xavier University. Dr. Melissa M. Moon is an associate professor of criminal justice at Northern Kentucky University. Joseph A. Hendry, PSP, is a retired lieutenant of the Kent State Police Department. He is a certified law enforcement executive and is the Director of Risk Assessment for the ALICE Training Institute.