Loss Prevention Lab

Working at the Loss Prevention Research Council (LPRC)—an organization that tests loss-control solutions for suppliers and retailers—must be incredibly frustrating. The center, located on the campus of the University of Florida, houses a lab that mimics product displays found in typical retail environments. Over here is shelving filled with over-the-counter medications such as Prilosec and Imodium. Nearby sit 32-ounce containers of liquid Tide detergent. Also on the shelves are infant formula, razor blades, and dozens of other items that would be convenient to grab on the way home instead of stopping at the store. And the Red Bulls must tempt the late-night researchers.

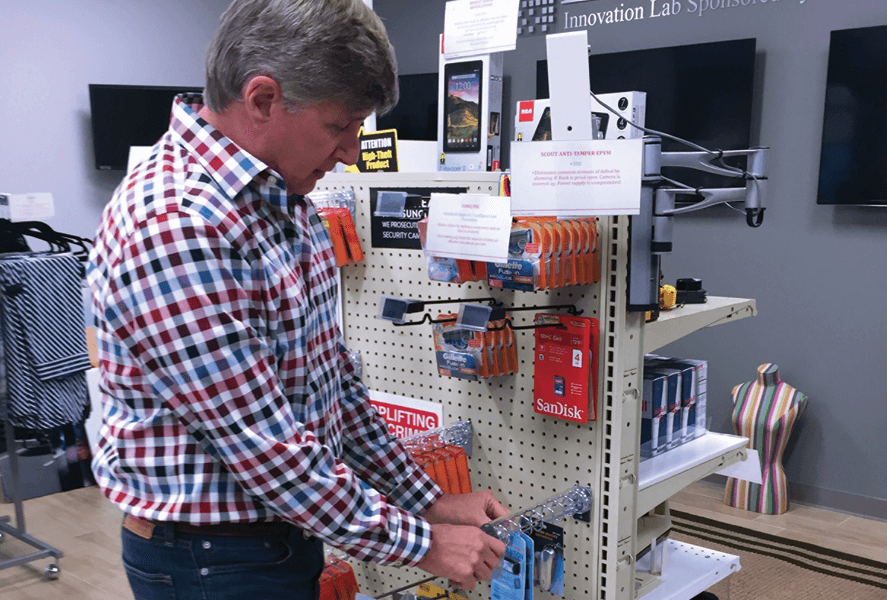

These items are among those most frequently stolen by shoplifters—also known as boosters—and they certainly aren’t for the taking by LPRC staff looking to streamline their errands. More than 75 technologies protect the goods, which range from Florida Gators polo shirts to bottles of 1800 Tequila. Screamer sirens, spider wrap, evidence tape, smart pads, shopping-cart analytics, “weaponized music,” RFID tags, and smart floor mats are among the tools that LPRC is testing on behalf of retailers and manufacturers to minimize loss without diminishing sales.

So what’s the most exciting new technology? Read Hayes, LPRC’s director, fingers point-of-sale–activated (POSA) benefit denial. Benefit denial tools operate not by making shoplifting riskier or time consuming, but by depriving the offender of the use of the item. Ink tags, which ruin garments if they aren’t removed by a special tool, are a well-known example of the benefit denial approach.

The new generation of benefit denial technologies, Hayes says, protects electronics. Special code can be injected into smartphones, tablets, printer cartridges—anything that contains firmware—that would render the product useless without an activation code. LPRC engineers have yet to defeat the technology, which can also be programmed to allow a device to work at certain times so that shoppers can try out the product in store.

RCA is one of the first to install the technology, using it in its Voyager tablet. Hayes says that Walmart is on the third phase of testing theft and sales of this device. A one-store test fared well enough to expand to 20 stores. It is now being rolled out for further testing in Walmart stores nationwide, he says. He will be discussing findings shortly with big-box retailers.

Of course, a retailer suffers a loss just the same if an unusable item is stolen. So public awareness of the protection technology, such as through signage or staff explanations, is critical to this approach. Walmart has used yellow warning signs for the RCA tablet. And because the protected product is featured by the retailer, Hayes says this technology attracts brands whose products are not leaders in their fields, such as RCA’s tablet.

Hayes speculates that this type of technology could augur a paradigm change, such as occurred when the theft of gift cards dropped after shoplifters realized the cards had to be activated by a clerk. That works as long as a legitimate buyer doesn’t have a problem activating a product.

I am joining two members of the LPRC team, Hayes and research team leader Mike Giblin, to witness an ongoing loss prevention test at one of the stores affiliated with the LPRC, a Best Buy in Gainesville, Florida. LPRC and Best Buy were testing various devices to prevent theft of Apple Lightning power devices without discouraging legitimate purchasers. This would be phase one. Assuming useful results, phase two would expand specific measures to additional stores. For any tools that passed muster, a third phase would test how they perform in various environments, regions, store types, and so on.

LPRC’s extended laboratory is a group of more than 20 Gainesville-area stores from global chains—including Publix, Michael’s, CVS, AutoZone, and Macy’s—that serve as innovation zones. If one of these retailers wants to establish proof of concept or conduct a small-scale test, they are right in LPRC’s backyard.

Under scrutiny at Best Buy are devices that make it difficult to easily slide multiple power cords and other power-related products off peg hooks. Researchers are also testing a system where motion sensors near the products trigger cameras that feed to video monitors at each end of the aisle and show who is near the high-theft products. The idea is that, upon seeing him or herself on the monitor, the shoplifter would abandon the theft.

Part way through this multimonth testing period, LPRC interviewed shoplifters and legitimate shoppers alike. The results were surprising. While three-quarters of the shoplifters noticed at least some of the devices on the peg hooks, only 25 percent saw the video monitors, which were just a couple of body lengths away. Hayes and Giblin explain that offenders are so focused on their immediate vicinity that they are oblivious to activity just out of their range of operation.

So what did work? When asked which device would most deter them, thieves specified a device that required twisting a knob multiple times to release a product. Every twist caused a loud clicking sound.

While on site, we also want to determine where a booster might conceal goods. We make our way to a back corner of the store, where car stereos, speakers, and clearance items are on display. High shelves obstruct sight lines. The area is deserted, and it’s shabbier than the rest of the store, showing signs of neglect. The nearest staff member, easily visible in a bright blue shirt, is aisles away. No surveillance cameras are evident. An empty Coke can sits on a clearance shelf, bringing to mind the well-known “Broken Windows” theory, which posits that signs of neglect lead to increased crime.

These signs of abandonment—high shelves, obstructions, trash, less-popular items—“are unconsciously picked up by boosters,” says Giblin. Moving more attractive items to that section would increase foot traffic and discourage thieves looking to stash their items, but it might also contradict the conventional wisdom of placing the most attractive items front and center. So Hayes suggests to the retailer that it increase shopper traffic by better promoting the clearance items while installing public-view monitors, passive infrared-activated sound, and improved lighting options to signal to thieves that this area is no safe haven.