Only A (Lonely) Test

When Admiral Jamie Barnett took over as chief of public safety and homeland security at the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2009, he learned something interesting about the Emergency Alert System (EAS). “It had never been used, and it had never been tested,” he says.

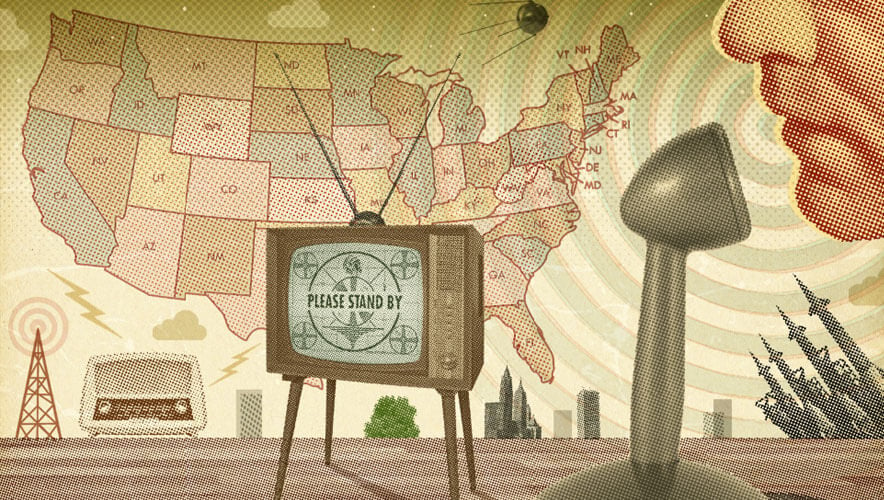

The never-been-tested part was surprising, because by that time the EAS had been around since 1997, when it replaced the Emergency Broadcast System. And the importance of having a well-functioning system seemed undeniable. “If the president were concerned that North Korean missiles were headed our way, he would have the ability, in essence, to preempt all the programming in the United States, pick up a mic, and say ‘We are under attack,’” Barnett says.

So Barnett sent a memo to the chairman of the FCC, expressing concerns about the viability of a system that had never been tested on a nationwide basis, and in fact had never even been scheduled for such a test. In turn, the FCC chairman sent the message up the chain, and it eventually reached the White House. After input from leading agencies such as the National Association of Broadcasters, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management System, and the White House Military Office, the administration decided to conduct a national EAS test on November 9, 2011.

What these officials were testing was a system that is a great-grandchild of the Cold War. Up until 1950, the government had no real method for broadcasting warnings to the nation at large. In 1951, U.S. President Harry S. Truman established an early emergency broadcast system, CONELRAD (Control of Electromagnetic Radiation), that was primarily designed to alert the public in the event of a Soviet attack during the Cold War. When new defense technology reduced the likelihood of a Russian bomber attack, CONELRAD was replaced by the Emergency Broadcast System (EBS) in 1963.

The EBS was tested on a weekly basis, with stations broadcasting a distinctive pattern of beeping sounds and a variation of the following announcement: “This is a test. For the next 60 seconds, this station will conduct a test of the Emergency Broadcast System. This is only a test.” While the system was never used for a national emergency (save for a false alarm in 1971), it was activated thousands of times for regional emergency messages such as severe weather warnings. In 1997, the EBS was expanded to include cable stations, and it became the EAS. (More recently, the government created a Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system to disseminate emergency alerts on mobile devices; see Security Management’s December issue for more coverage of that system.)

In sum, the EAS sends audio signals–that distinctive pattern of beeps that the EBS testing formerly made familiar–to 77 primary entry point stations. When these primary stations hear the signals, they immediately transmit it to other stations, so that in a matter of seconds the whole country is covered. “That irritating noise that you hear–that’s actually what the stations are listening for,” Barnett says. In fact, the government prohibits anyone from replicating those irritating beeps in a movie or television program or song. “People have been fined. The FCC would contact you,” he adds.

Although the sending of audio signals may not be cutting edge in terms of technology, it is resilient. “The system is designed to work when nothing else does. If the power is cut, this system will work,” Barnett explains. Since the security technology around the system is continually updated, hacking incidents have been rare; one of the few occurred in Great Falls, Montana, in 2013, when the EAS system at a television station was hacked to broadcast a zombie apocalypse message: “Civil authorities in your area have reported that the bodies of the dead are rising from their graves and attacking the living.”

The 2011 national test, which went generally well, showed there was room for improvement. An assessment found that there were issues affecting 10 to 20 percent of the national system, such as local equipment problems.

For example, some stations experienced a feedback loop in which they started to broadcast the test, but then immediately shut down. One station malfunctioned and went silent during the test, and because dead air is against FCC broadcasting rules, an operator threw on a Lady Gaga CD. “So people heard ‘There is an emergency alert’ and then [the song] Born this Way,” says Barnett, laughing.

Despite these problems, the FCC did not run another test until five years later. That test occurred last September. In a response to an inquiry from Security Management, FCC officials said that early reports indicated that the test went well.

“We have received over 24,000 initial reports from Emergency Alert System participants. The reports indicate that the vast majority of EAS participants successfully received and retransmitted the test alert,” Rear Admiral (ret.) David Simpson, chief of public safety and homeland security at the FCC, said in a statement. “After EAS participants file their more comprehensive reports, including information on any issues they encountered during the test, we will analyze the data and then work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other stakeholders to implement any needed improvements.”

However, given that such national testing is vital for maintaining a viable system, Barnett and others argue that it should be done more frequently.

“I think five years is too long,” Barnett says. “My thought originally was that it needed to become routine, so every two to three years would be about right.”

Nelson Daza, an incident communications expert with Everbridge, argues in favor of annual national testing, to ensure readiness and point out potential infrastructure problems. “FEMA reminds everyone to test local emergency plans and family emergency plans at least once per year, so why does the government not mandate an annual EAS test?” Daza asks. “If we let these systems lie dormant until we need them for an emergency, there’s a very real possibility that we may not be able to get these critical messages out.”

Daza also says he feels that some of the devices and protocols of the EAS need to be updated. He says that the hardware maintained by broadcasters is of limited functionality–it can only broadcast text information in ticker-tape style across the top or bottom of a television set. “Since the EAS system is vital to our national security and to our public safety, it should undoubtedly be a state-of-the-art system,” he explains.

But Daza does disagree with those who argue that the U.S. population’s general move away from broadcast televisions and radio, in favor of Internet-based programming and wireless communications, is making the EAS obsolete.

“WEA, television alerts, and radio alerts are just different channels for delivering a message. Tens of millions of people listen to the radio in their cars every day, and the average person in the U.S. still watches 5 hours of television every day,” he says. “With that many ears and eyes, it would be a mistake to think WEA, which distributes only mobile alerts, will replace emergency alerts broadcast via TV and radio.”