A Strategy for Fusion Centers

What do a spike in copper wiring thefts in Indiana and a pattern of attempted break-ins at utilities in Ohio have in common? Potentially, quite a lot, say security officials involved with fusion centers around the United States. Copper wiring theft from cell phone towers can disable emergency notification systems, and patterns of criminals testing the perimeter security at utilities can signal a larger, malicious plan.

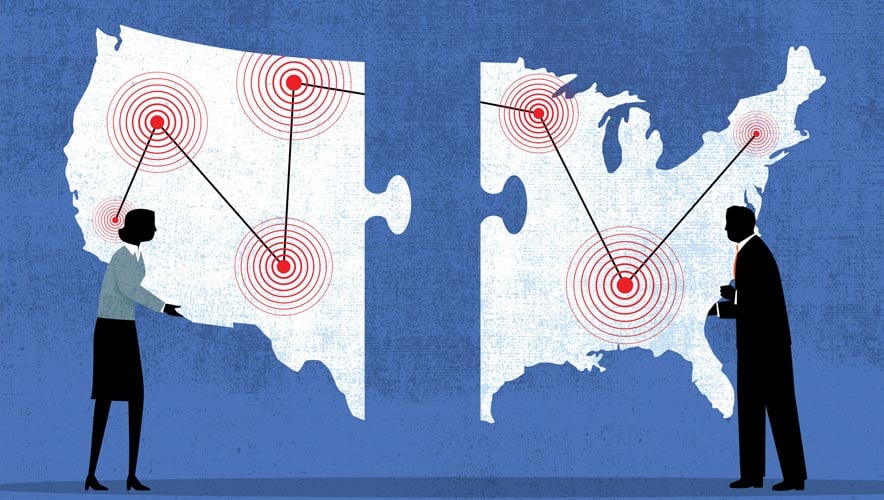

The goal of the 78 intelligence-sharing fusion centers across the nation is to take note of seemingly isolated events and connect the dots to identify sinister plots before they come to fruition. A post-9-11 initiative to increase intelligence sharing among federal, state, local, and private sector entities, while providing both federal and state funding, resulted in the creation of the centers over the last decade.

Fusion centers are owned and operated by state and local governments, but they receive funding from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and other federal agencies. Each governor designates a primary fusion center in his or her state and can appoint designated fusion centers in major metropolitan areas, as well. The nationwide system of fusion centers is known as the National Network.

In 2014, operational costs for the National Network increased by 6.5 percent to more than $328 million. Fusion centers are primarily funded by state expenditures, but also through local support as well as federal grants. There is no direct federal oversight of the individual fusion centers, but DHS conducts an annual assessment of the National Network to make sure the programs comply with grant requirements. Each center has a coordinating body that offers oversight, as well.

Although DHS has supported the initiative through funding and manpower, the centers have received criticism. Advocacy groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Privacy Information Center contend that the information collection and sharing, as well as initiatives such as Suspicious Activity Reporting, infringe on the privacy of citizens. In 2014, DHS increased the amount of classified information available to fusion centers, and experts say centers need more clarification regarding who has access to such information, since private sector partners may not legally be allowed to access classified data.

In 2012, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released the results of a two-year investigation into the centers’ operations, finding that the centers had not uncovered any terrorist attacks, lacked procedures for sharing intelligence, and spent federal grant money on frivolous technology.

“The subcommittee investigation found that the fusion centers often produced irrelevant, useless, or inappropriate intelligence reporting to DHS,” the report found. Anonymous DHS officials interviewed by the subcommittee called the centers “pools of ineptitude” that produced “a bunch of crap.”

Since then, fusion centers have developed guidelines, strategies, and regulations to improve both individually and as a network, says W. Ross Ashley, III, executive director of the National Fusion Center Association (NFCA). The association helps coordinate, advocate, and educate people across the government about the value of the centers, he says.

“We are simply here to help give a voice to fusion centers from a national network perspective,” Ashley tells Security Management. “Each individual fusion center serves its own constituency, but also participates as part of a nationwide network as a national resource.”

Last year, NFCA worked with stakeholders from the intelligence community, public safety, emergency management, and public health sectors to develop the National Strategy of the National Network of Fusion Centers, a three-year program intended to “systematically improve intelligence information sharing beyond existing and successful criminal intelligence in support of law enforcement investigations,” the strategy states.

Ashley stresses that each fusion center is unique in its capabilities and activities, but NFCA saw a need to produce a coherent national strategy that spells out the overarching goals of the programs. The first goal—and the most important, says Ashley—is to uphold public confidence through the safeguarding of information and the protection of privacy and civil liberties.

“In order for fusion centers to be successful, they have to have the inherent trust of the communities they serve,” Ashley explains. “The only way they do that is to ensure that privacy protections are in place, and that civil rights and civil liberties are being adhered to in every step of the process.” As a part of this goal, every fusion center must have a federally approved privacy policy in place, as well as an assigned privacy officer.

The other goals include supporting engagement with federal, state, local, and private partners to improve information sharing; strengthening the connections among fusion centers; and increasing connectivity between fusion centers and the federal government.

Bill Vedra, the former head of Ohio’s Homeland Security Division, says that when he helped start Ohio’s primary fusion center in 2007, creating a strong privacy policy was a priority.

“It’s a partnership of understanding,” Vedra explains. “We all want safe cities, states, and country, and it requires the sharing of information, but how you handle that information is critical to preserving the freedoms that we enjoy. So it’s a balance, and I think Ohio was, and still is, very cognizant of the need to share information in a way that protects the civil liberties of everyone.”

Early on, Vedra says that strengthening the trust between public and private partnerships was imperative to the centers’ goals.

“Everyone had the right motive, but it was building that trust to enable that cooperation and collaboration to get people to share information,” he explains. “The whole premise was, we need to prevent if at all possible another 9-11, and part of the 9/11 Commission directive was to share information better and build this platform where the right people at the right levels get the right information.”

For example, Vedra says a challenge was getting the private sector to report seemingly innocuous events, such as failed break-ins, to the fusion center. “Suspicious activity is an example that a utility may see, and we could share it with other utility members in the community,” he says. “When there was a theft or attempt at gaining access to a utility facility, we could tell whether it was an isolated event or something more criminal, such as terrorism. The other utilities, for example, could be on the lookout for the same thing.”

An important aspect of the fusion center program is the lateral sharing it enables, Vedra notes. Beyond the vertical local-state-federal collaboration in one community, localities can share information with other communities in their region to detect large-scale patterns. Ohio’s fusion center also focused on creating more community involvement, so information sharing became a full-circle process.

“One of the drivers of the fusion center concept was being able to get actionable information up to decision makers, to get the bigger view of what’s happening across the country, and then being able to get that back down so it can be shared with locals,” Vedra explains.

Today, the role of fusion centers has evolved. The 2014 National Network report notes that “fusion centers provide the most benefit and have the greatest impact when they can apply their capabilities across the full spectrum of homeland security mission areas.”

Indeed, in 2014, fusion centers provided an increased amount of direct support to special events and federally declared disasters in their communities, and the National Strategy focuses on formalizing the support of other national security priorities beyond terrorism, such as investigating cyberthreats and criminal activity. And earlier this year, three adults were convicted of sex trafficking after fusion centers in Florida, Louisiana, and California worked together to identify the ringleaders.

Ashley says that NFCA is using an implementation plan to track how the National Strategy has been applied at the fusion centers across the country over the past year. He says the association hopes to gather metrics about the National Network through the strategy and present the information to legislators to encourage ongoing federal support.