Change Tactics

Late one evening this past March, a woman drove her vehicle to a security gate outside the White House fence line and left a package she claimed was a bomb. U.S. Secret Service agents at the scene confronted the woman but were unable to apprehend her, and the package sat unattended as traffic drove by. Eleven minutes later, the Secret Service called the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) bomb squad, but failed to mention that the woman had identified the package as a bomb—instead calling it a suspicious package.

While law enforcement was responding, two high-ranking Secret Service agents were allegedly drinking and driving following a retirement party. They drove through a temporary barricade within a few feet of the package. Yet, they were not given a sobriety test and were allowed to leave the scene. The woman was later arrested—by a different police agency on unrelated charges—but the agents were not immediately reprimanded.

Secret Service Director Joseph P. Clancy was not informed of the incident, and only discovered what had happened because a former agent told him that an e-mail about the activities was circulating. The incident was yet another in a long list of embarrassments faced by the agency in the last few years.

For more than 100 years the Secret Service has had the full-time responsibility of protecting the president of the United States. As a protective detail, it’s had numerous unsung successes, yet lately it seems the only coverage the service is getting is for its failures as an organization.

In an effort to reform the agency, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Jeh Johnson commissioned two independent reviews of the Secret Service, which recommended a host of changes and resulted in a complete overhaul of the service’s leadership.

However, instead of doing what many assumed—appointing an outsider to take charge of the notoriously insular organization—President Barack Obama and Johnson appointed Acting Director Clancy as the 24th director. Clancy began working for the service in May 1984 in its Philadelphia Field Office before being transferred to the Presidential Protective Division.

“The president and I considered several strong candidates for the position, including those who had never been with the Secret Service,” Johnson said in a statement. “Ultimately, Joe Clancy struck the right balance of familiarity with the Secret Service and its missions, respect from within the workforce, and a demonstrated determination to make hard choices and foster needed change. I am confident Joe will continue this management approach.”

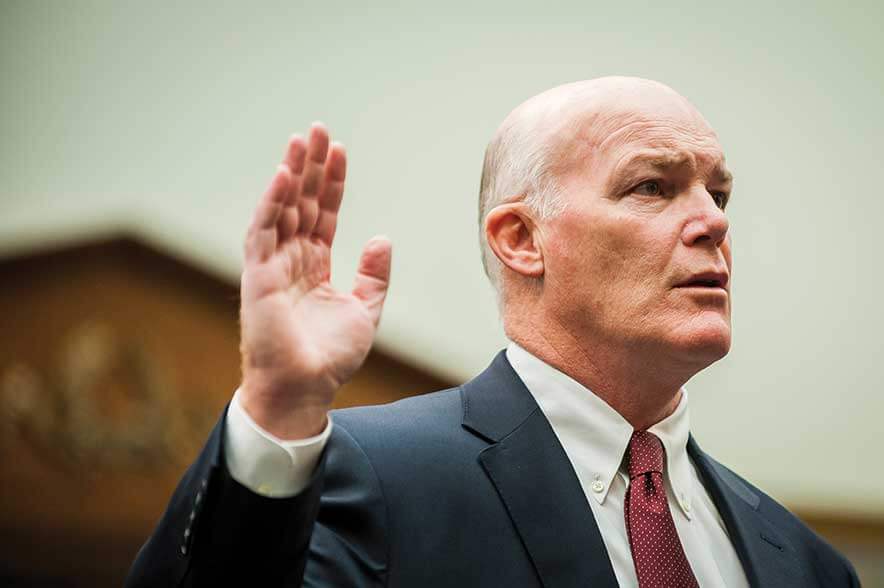

Clancy became the director a few weeks before the March incident, and as a change agent he’s come under fire from Congress for the Secret Service’s actions.

“It’s going to take time to change some of this culture,” Clancy said in a statement to the House Oversight Committee. “There’s no excuse for this information not to come up the chain. That’s going to take time because I’m going to have to build trust with our workforce.”

His remarks drew strong opinions from members of the committee, such as Rep. Nita Lowey (D-NY), who suggested that those not interested in changing the culture of the service “go get another job,” to Rep. Chris Stewart’s (R-UT), “Dude, you don’t have to earn their trust. You’re their boss. They’re supposed to earn your trust.”

Clancy says he is committed to improving the agency, but can he be an effective change agent? Or is an outsider needed to hold people accountable and overhaul the Secret Service?

Julie Battilana, an associate professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, has been studying change agents for more than a decade. What she’s found is that it’s not enough for change agents to develop a vision, align people in their organization with the vision, and evaluate the process of that change implementation.

“It was clear to me that you could still engage in every single step, and fail miserably when it comes to implementing change,” she says. “So I wanted to go one step beyond and try to understand other factors of success. And that led me to study leadership skills.”

She published her findings in Harvard Business Review’s “The Network Secrets of Great Change Agents” with Tiziana Casciaro. The research revealed that individuals who are central to their organization—employees that other people go to for advice—“are significantly more effective change agents,” Battilana explains. Regardless of their position in the formal hierarchy, these individuals have influence that gives them a clear advantage over others seeking to be change agents.

Battilana also found that the type of network an organization has can also influence how successful a dramatic—or divergent—change can be. For instance, if an organization has a cohesive network where all employees are connected to one another, implementing a divergent change can result in strong pushback, Battilana says. “Because all these people are connected to each other, it only takes one of them to think it’s a bad idea and try to convince others, and they can kill the idea.”

However, if you have a rigid network—like a bridging network where only the change agent is connected to employees who are not connected to each other—it allows change agents to tailor their discourse with different audiences to try to convince them to get on board.

“Also, if these different audiences are not connected to each other…it will take longer for them to create a coalition against you,” she adds. “This is critical because it’s divergent change, and divergent changes generate more resistance.”

Battilana also examined how personal relationships between change agents, endorsers, fence-sitters, and resisters affect organizational change. Interestingly, personal relationships with endorsers were not as crucial as those with fence-sitters, because the latter are likely to support the change on its merits—not based solely on whether they like the change agent.

“Having a stronger connection with the fence-sitters is always helpful because those people are ambivalent about the change,” she explains. “They can see the pros and cons, and sometimes they’re just indifferent.” Change agents can use these connections to try to get them to become endorsers, and can also use other members of their coalition that have a connection to get them on board as well.

When it comes to resisters, having a personal relationship with the change agent can be a double-edged sword. If the change isn’t radical, change agents can leverage their personal relationships, and resisters may back them. But if the change brings “huge implications for me and for other people, it’s unlikely that for the sake of our relationship I’m going to accept this really unwanted outcome,” Battilana says.

“And what I’ve seen over and over in different settings is that, in fact, when people have a connection to resisters of a divergent change, they very often waste a lot of time thinking if there’s one person I can convince, it’s this resister because I know him or her,” she explains. “But what they don’t realize is it’s a two-way street, so what’s happening then is those resisters end up influencing the change agent. And the change agents often give up on the change and do not continue.”