A Face in the Crowd

Law enforcement officers in Pennsylvania were investigating a shooting in July 2013, but they were able to identify only one of the two suspects involved. “They’d dealt with him before, but they could not ID the other suspect,” explains Lucinda Stone, who works at the Pennsylvania Office of Administration.

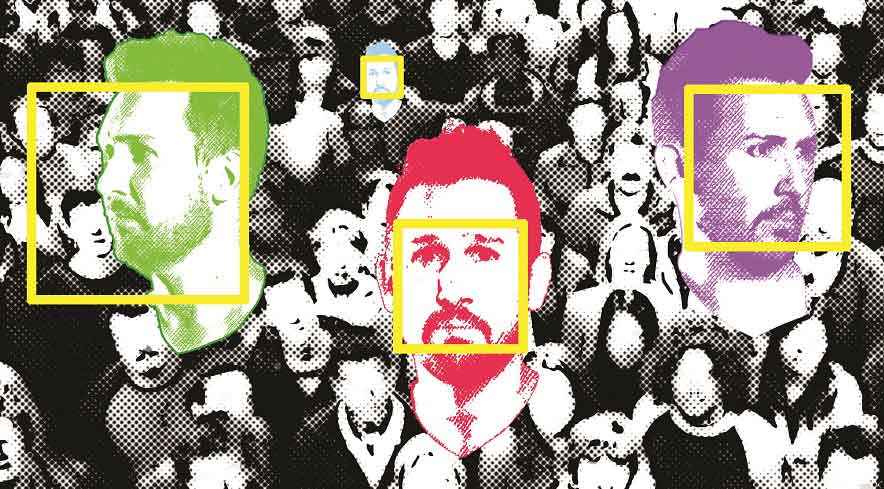

A witness who knew the unidentified suspect by a nickname provided police with access to a Facebook page. “They pulled the Facebook picture [of the suspect] and they ran it,” Stone tells Security Management. Using a facial recognition algorithm and other technologies, police were able to compare that suspect’s photo to millions contained in the state’s bookings database. “Once they got the results back, upon further investigation they were able to confirm that this individual was the second shooter.”

The law enforcement officer was able to identify the suspect by using the facial recognition system of the Pennsylvania Justice Network (JNET). JNET is an online portal that facilitates information gathering and sharing among municipal, state, and federal law enforcement entities in the state, and is maintained by the Pennsylvania Office of Administration. With more than 38,000 active users, JNET provides various types of data to the criminal justice community, including arrest, incarceration, and driving records. Beyond the shooting incident described above, the facial recognition system contained within JNET has helped solve numerous cases, including homicides, burglaries, robberies, and fraud and identity theft.

But facial recognition is only part of the success story behind JNET. The Web-based system has improved the accuracy of data provided to participating agencies, explains Harry Giordano, special projects manager at JNET.

Criminal records, a large portion of that data, are easier to sift through and investigate thanks to the online portal.The mug shots included in these records provide an alternative to biometric identifiers, like fingerprints, which are not as ubiquitous as images of suspects at the scene of a crime.

In mid-2011, JNET administrators were looking to upgrade the facial recognition portion of the portal, which was installed in 2003. Technology had improved dramatically during that time, and newer, more robust algorithms were available. With some 3.4 million mug shots included in the various JNET databases, the old system had trouble keeping up. And the image database was only growing. When a suspect’s photo goes into the JNET database, that image remains there for the foreseeable future. “When your mug shot is taken and your fingerprints are captured, they’re combined and put into our system and verified that the individual has a state ID number, and that stays with the individual his entire criminal career, unless his conviction is overturned or expunged,” explains Giordano.

Photos in the database can come from multiple sources, including surveillance images from the JNET Watchlist, which is integrated into the JNET facial recognition system and lets law enforcement add photos from ATM, retail, and a variety of other surveillance cameras. “Users may enroll unidentified investigative probes on the facial recognition watchlist,” explains Stone. Then, any time an individual is arrested and photographed, the system does a lights-out search for any possible candidates throughout the surveillance images. The investigator who enrolled the subject on the watchlist is notified of a possible candidate via e-mail. Then he or she can log on to a secure site and view the candidate. “It is up to the investigator to view the possible candidate and perform other investigative methods to either confirm or deny a match,” she says.

JNET uses a system from DataWorks Plus, LLC, for taking mug shots when anyone is arrested. “All the cameras, all the equipment, all the capturing equipment is exactly the same,” Giordano says of the mug shots taken when booking suspects across the state. “All the data elements are controlled by a central site, and the lighting is a specification that we put out that everybody follows.” This standardization simplifies the workload for the facial recognition system.

Even so, Giordano says the old facial recognition system was unreliable and gave inconclusive search results due in part to a poor algorithm, and JNET wanted a new algorithm that could “match the quality of our mug shot system.”

JNET put out a contract for the provider of a new facial recognition algorithm, and ended up choosing a Web-based product, from DataWorks Plus (which supplied the mug shot system), called FACE Plus. The bid also included the NeoFace facial recognition matching software technology from NEC that works with the technology from DataWorks Plus. The system was installed in May 2012.

Giordano had worked with NEC in the past and had long used the company’s automated fingerprint identification technology. In addition, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) vets facial recognition technologies through its Face Recognition Vendor Test, which is designed to provide law enforcement and the U.S. government with information on the deployment of such technologies. Giordano was impressed that NIST had granted NEC’s facial recognition technology the highest performance evaluation for three years in a row, most recently in July.

Now, when law enforcement has a photo of an individual it wants to investigate, one of the first steps is running that photo against the mug shot database on JNET. “If they don’t know who that person is, they then take the image, upload it into the system, and run a search, and they get back several rows of results,” Giordano says. “The results are ranked–there’s no positive ID, so they have to through the results and see if there’s anybody that they may investigate further.”

The facial recognition algorithm from NEC combines with a 3D pose-correction algorithm from Cognitec. “We use it when the pose is not head-on, or what we call an ‘off-pose,’” Stone says. The head-on poses, which are more standard, make it easier for the facial recognition system to compare faces.

Stone adds that investigators and detectives receive training and can access the facial recognition system. She says the tool has played a large role in convicting many suspects, adding that the ubiquity of photos on social media sites, like Facebook and Instagram, also plays into the success law enforcement has had using the program. Stone says that the high quality of images on the site is a “great” aid for law enforcement when using the facial recognition tool.

Both Stone and Giordano belong to the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG), an FBI-sponsored organization that establishes standards for image-based comparisons of human features and offers recommendations for further developments in the field. According to Giordano, other states represented in the working group have sought to replicate JNET’s success with the facial recognition system and training program.

“Our training is unique in that our system is unique…Pennsylvania is one of the only states that has all booking centers linked so that our users search the entire state database,” Stone says. She adds that JNET allows any investigators or detectives to have access to the software as long as they complete the training, whereas “some of the other states have all images sent to a central location to be run.”

The system doesn’t just help police catch bad guys. Giordano says that the facial recognition capability has also allowed law enforcement to identify witnesses who can help solve cases, as well as prove innocence. “Biometrics goes both ways,” he says.

He also emphasizes that the facial recognition software is merely an investigative technique, and legally admissible evidence must be provided to corroborate a matching photo to convict someone. “Facial recognition is not certified like fingerprints, so it does not go to court,” he explains. “This is only one tool in the investigator’s toolkit to capture someone. He has to go and develop his case and present his case in court as an investigator.”

Stone also emphasizes that a positive image match is not enough to put someone in jail. She says that the shooter who was identified positively through a Facebook photo was never convicted because no one was willing to testify against him. “But at least law enforcement knows who he is,” she says.