Lawmakers Hold Hearing on the Use of Credit Checks in Hiring Decisions

Lawmakers on a House Financial Services' subcommittee last week examined amending the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) [.pdf] to prohibit a current or prospective employer from using credit reports to make employment decisions such as hiring, firing, or promotion.

Witnesses who support the rights of employers to use such reports told members of the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit that the information is not used in a vacuum, but is among the many tools companies use to make good hiring decisions. Opponents contended that credit scores are often inaccurate and have not been linked to inappropriate workplace behaviors, such as theft.

One witness, Stuart Pratt of the Consumer Data Industry Association in Washington, D.C., argued that credit checks are helpful in thwarting employee theft. He quoted a study from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, which analyzed 959 cases of occupational fraud perpetrated between 2006 and 2008. The study found that the top two predictors of employee theft were living beyond one’s means (found in 39 percent of cases with a median loss of $250,000) and experiencing financial difficulties (found in 34 percent of cases with a median loss of $111,000).

Chi Chi Wu, staff attorney with the National Consumer Law Center in Boston, Massachusetts, disagreed with the idea that credit checks can predict employee theft. She noted that the only study to directly measure the connection between weak credit and employee misconduct was "Further Investigation of Credit History as a Predictor of Employee Turnover," which was released in a presentation to the American Psychological Society in 2003. The study found no correlation between credit history and job performance, according to Wu.

Wu also told the subcommittee that the underlying hypothesis behind the use of credit checks is flawed. “Credit reports were designed to predict the likelihood that a consumer will make payments on a loan, not whether he would steal or behave irresponsibly in the workplace,” she said.

Witness Anne Fortney of Hudson Cook, LLP, told the subcommittee that even if credit checks were not designed for preemployment screening purposes, employers should be able to include credit checks as one of many tools available to help chose the right candidate for a job. Fortney also noted that safeguards are already in place under existing law. The FCRA requires that employers notify the employee or applicant of any negative credit information and provide the opportunity to correct such information before an employment decision is made.

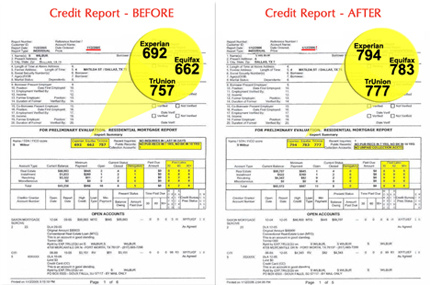

Even in light of the FCRA, errors are too widespread and often difficult to correct, noted Wu. She cited an ongoing series ofreportsby the Federal Trade Commission that has found errors on 12 to 37 percent of credit reports.

Lawmakers were especially concerned with the effect of negative credit reports due to delinquent medical payments. Though some witnesses disputed the idea that medical debt was different from other types of debt, others contended that medical debt does not represent bad decision making like credit card debt, for example, and should not be considered in employment decisions.

Mark Rukavina of The Access Project, a nonprofit institute researching access to health care, noted that lenders often disregard medical debt when determining whether a borrower is a good credit risk. “If other accounts are current, a medical debt or outstanding medical bill is not a good predictor of creditworthiness,” he said.

Lawmakers argued that the most pressing concern is the economy. “The current system facilitates the denial of employment to those who have bad debt, even though bad debt often times results from the denial of employment,” say Congressman Luis V. Gutierrez, chairman of the subcommittee. Wu agreed. “Using credit history, especially in an economy with such massive numbers of job losses as the current one, creates a grotesque conundrum,” she said. “Simply put, a worker who loses her job is likely to fall behind paying her bills due to a lack of income…this worker now finds herself shut out of the job market because she’s behind on her bills.”

The bill has 53 cosponsors and remains in the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit. Action on the issue has also been seen on the state level. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have introduced legislation to outlaw or limit the use of credit checks for employment purposes.