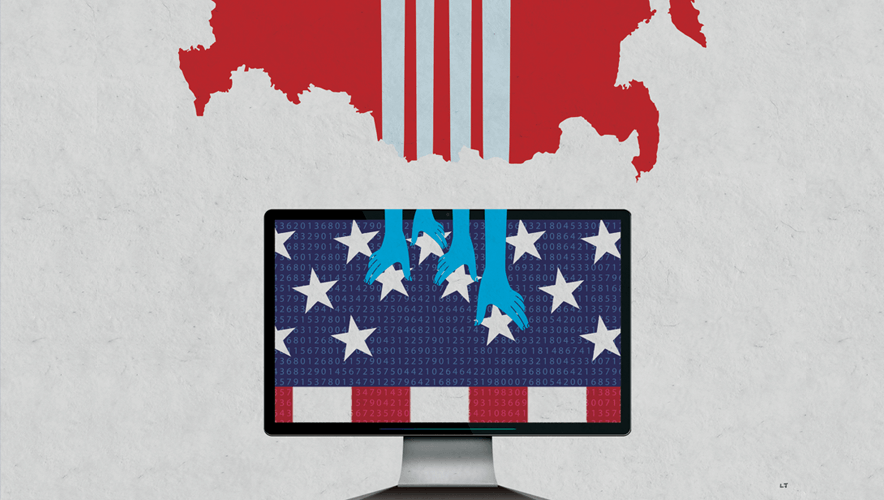

Attacks on the Record

It was, in the opinion of some experts, a long overdue action. But it finally came. On March 15, 2018, the U.S. federal government issued sanctions against Russia for its interference in the 2016 U.S. elections and malicious cyberattacks on critical infrastructure.

"The administration is confronting and countering malign Russian cyber activity, including their attempted interference in U.S. elections, destructive cyberattacks, and intrusions targeting critical infrastructure," said U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin in a statement. "These targeted sanctions are a part of a broader effort to address the ongoing nefarious attacks emanating from Russia."

The sanctions targeted five entities and 19 individuals for their roles in these activities and prohibit U.S. persons from engaging in transactions with them. Mnuchin also said that the department intends to impose additional Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) sanctions to hold Russian government officials and oligarchs accountable.

The economic penalties are an attempt to punish Russians for their role in various forms of cyberactivity, including the NotPetya attack, which the White House and the British government have attributed to the Russian military.

NotPetya "was the most destructive and costly cyberattack in history," Mnuchin said. "The attack resulted in billions of dollars in damage across Europe, Asia, and the United States, and significantly disrupted global shipping, trade, and the production of medicines. Additionally, several hospitals in the United States were unable to create electronic records for more than a week."

The sanctions were also in response to the efforts of Russian government cyber actors in targeting U.S. government entities and critical infrastructure—including energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors—since at least March 2016.

Nick Bilogorskiy, cybersecurity strategist at Juniper Networks, says that the United States should be "very concerned" about these attacks.

"For one, they could cause prolonged electrical outages and blackouts because our electrical grid infrastructure lacks sufficient redundancy to sustain these attacks," Bilogorskiy explains. "In the worst-case scenario, cyberattacks on nuclear power plants could cause them to explode and cost human lives."

One example of a near-worst-case scenario was the recent incident targeting Schneider's Triconex controllers at Saudi Arabia's power plants. A cyberattack hit its systems, Bilogorskiy says. It was intended to cause an explosion, but an error in the attack's computer code caused it to fail.

To educate network defenders on how they can reduce the risk of similar malicious activity in their networks, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the FBI released a joint technical alert detailing Russia's campaigns to target critical infrastructure.

"DHS and FBI characterize this activity as a multi-stage intrusion campaign by Russian government cyber actors who targeted small commercial facilities' networks where they staged malware, conducted spear phishing, and gained remote access into energy sector networks," the alert said. "After obtaining access, the Russian government cyber actors conducted network reconnaissance, moved laterally, and collected information pertaining to industrial control systems (ICS)."

The alert split Russia's activity into two categories for victims: intended targets and staged targets. Russia targeted peripheral organizations, such as trusted third-party suppliers with less-secure networks, that the alert calls staging targets.

"The threat actors used the staging targets' networks as pivot points and malware repositories when targeting their final intended victims," the alert explained. DHS and the FBI "judge the ultimate objective of the actors is to compromise organizational networks, also referred to as the 'intended target.'"

Compromising these networks involved conducting reconnaissance, beginning with publicly available information on the intended targets that could be used to conduct spear phishing campaigns.

"In some cases, information posted to company websites, especially information that may appear to be innocuous, may contain operationally sensitive information," the alert said. "As an example, the threat actors downloaded a small photo from a publicly accessible human resources page. The image, when expanded, was a high-resolution photo that displayed control systems equipment models and status information in the background."

After obtaining information through reconnaissance, the threat actors weaponized that information to launch spear phishing campaigns against their targets that referred to control systems or process control systems. These campaigns tended to use a contract agreement theme that included the subject "AGREEMENT & Confidential," as well as PDFs labeled "document.pdf."

"The PDF was not malicious and did not contain any active code," the alert said. "The document contained a shortened URL that, when clicked, led users to a website that prompted the user for email address and password."

The phishing emails also often referenced industrial control equipment and protocols and used malicious Microsoft Word attachments—like résumés and curricula vitae for industrial control systems personnel—to entice recipients to open them.

Additionally, the hackers used watering holes to compromise the infrastructure of trusted organizations to reach their intended targets.

"Approximately half of the known watering holes are trade publications and informational websites related to process control, ICS, or critical infrastructure," the alert said. "Although these watering holes may host legitimate content developed by reputable organizations, the threat actors altered websites to contain and reference malicious content."

The threat actors were then able to collect users' credentials that would allow them to log in to their profiles elsewhere. They also used this access to compromise victims' networks where they were not using multifactor authentication.

"To maintain persistence, the threat actors created local administrator accounts within staging targets and placed malicious files within intended targets," according to the alert.

Once the attackers had gained access to their intended targets, they used that access to infiltrate workstations and servers on corporate networks that contained data on control systems within energy generation facilities. The attackers also copied profile and configuration information for accessing ICS systems.

This method of compromise is not new and has been demonstrated in cyberattacks on the corporate sector over the past few years, says Tom Patterson, chief trust officer at Unisys.

"Just as with the Target cyber breach several years ago, they first attacked supply chain partners, which are often less protected, and then used their access to compromise the actual target company," Patterson explains.

The level of access the attackers were able to gain is concerning, Patterson adds, because it could potentially give them the ability to disrupt functions of critical infrastructure, such as providing heat in the winter.

"Since many of these ICS devices are connected to corporate networks in today's enterprise, and oftentimes they are older devices built on insecure operating systems, this gives the threat actors and their political or economic masters the ability to disrupt or destroy systems at the push of a button," Patterson says.

Brian Harrell, CPP, former operations director of the Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center and director of critical infrastructure protection programs at the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), agrees with Patterson that these kinds of attacks are not new.

What is new, says Harrell—now president and CSO of the Cutlass Security Group—is that the United States is choosing to acknowledge and attribute the activity, publicly, to Russia.

"While attribution is often difficult, nation-state actors like Russia likely have the most interest in compromising industrial control networks, not to necessarily take anything, but to prove they can access our systems and cause us to feel unsettled," he explains.

While the U.S. government has taken the approach to name and shame, Harrell says he thinks its unlikely that the public actions will deter Russia's behavior.

"Unfortunately, the current DHS alert, legal indictments, sanctions, or public shaming will not have any effect on Russian cyber intrusions," he adds. "However, we must continue to increase pressure until they change their behavior and become a responsible member of the international community."

In the meantime, the FBI and DHS recommend that network administrators review their IP addresses, domain names, file hashes, and other signatures that were provided in their alert. The agencies also recommended adding certain IP addresses cited in the alert to their watch lists.

"Reviewing network perimeter netflow will help determine whether a network has experienced suspicious activity," according to the alert.

The two agencies also compiled a list of 28 actions for network administrators to take in response to Russia's activity, including monitoring virtual private networks for abnormal activity, deploying Web and email filters, and segmenting critical networks and control systems from business systems and networks.

"What DHS is recommending, at the end of the day, are properly built ICS networks, monitored so organizations can detect attacks and are plugged into external threat intelligence, with incident response plans and board-level strategic roadmaps," Patterson says.