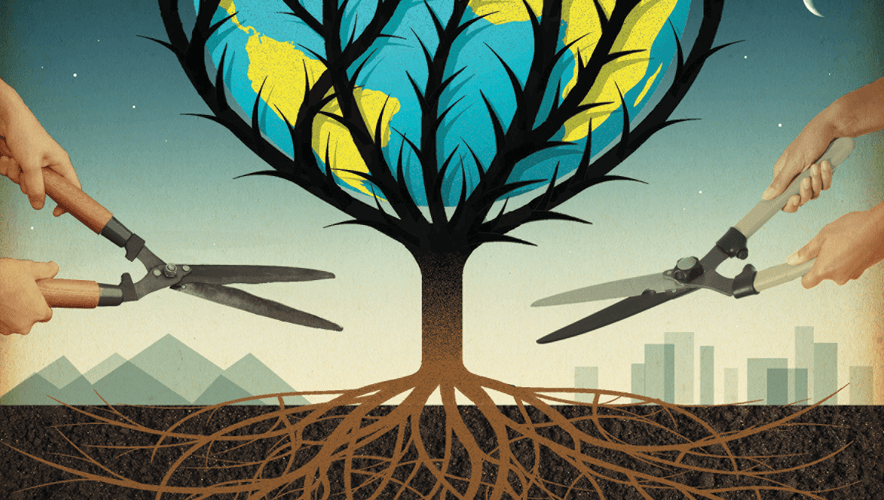

The Roots of Risk

Risk management is on the rise in many security programs, as managers develop more sophisticated methods and strategies for evaluating the threat landscape to better protect people, property, networks, data, and other assets.

But on the far horizon of risk management, another strategy may be on the rise: an increased focus on the root-cause factors underlying the threat landscape, according to expert opinion and a new report, The Meaning of Security in the 21st Century.

The global study, conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)—the research and analysis division of the Economist Group, which publishes The Economist magazine—surveyed 150 board members and various C-suite executives, including CSOs such as Troels Oerting of Barclays and Henry Shiembob of Cognizant Technology Solutions. About half of the survey respondents worked for large global corporations, with annual revenues exceeding $500 million.

The study found that large-scale sources of societal conflict—including resource scarcity, ethnic or religious differences, poverty, and income inequality—drive many security risks, and in an unstable world these conflicts are likely to increase over time. Thus, business leaders will be dealing with an increasing number of threats that have their roots in disruptions beyond corporate borders.

In the next five years, the top three root causes, according to the survey, will be political or ideological differences (cited by 37 percent of respondents); poverty or income inequality (36 percent); and scarcity of key resources (35 percent).

Addressing these underlying problems was traditionally considered beyond the scope of a corporate security program, for several reasons. According to survey respondents, the three leading barriers to addressing these root causes of risk are “no agreement on how to best address these issues” (30 percent); “it is contrary to the corporate culture to engage in such activities” (27 percent); and “taking an active role would involve a level of interference in political questions that stakeholders would condemn” (27 percent).

Despite these current barriers, there may be a growing role in the future for CSOs to address underlying issues, the study found.

“Ethnic and religious tensions are arguably beyond the jurisdiction of corporate involvement. But income and inequality and poor education are less so,” the report argues. “For this to change, discussion of the role that businesses might play would have to go beyond corporate leadership and reach an audience among the general public.”

The findings are apt, because the future will hold opportunities for CSOs to have a growing role in addressing root-cause issues, according to two longtime security leaders who shared their on-the-ground perspective on the study in recent interviews with Security Management. Both executives are active members of ASIS’s CSO Center for Leadership and Development.

Martin Barye-Garcia, security director for the Americas with Mars, sees the issue in a global context. Although the corporate security function in many organizations has been “very U.S.-centric” in the past, the effects of globalization have caused the role of global security to grow, both in scope and responsibility, he says.

Now, it is becoming more common for organizations to consult the CSO, or their regional security directors, when addressing certain root cause security issues. These issues include the sustainability of the supply chain, geopolitical stability, transnational crime trends, and the effects of the global economy on business dealings abroad, Barye-Garcia says.

Of course, this varies from company to company. “This level of involvement by global security is many times directly related to the level of social responsibility, the type of company culture, and stakeholder appetite for participation in greater humanistic endeavors,” he explains.

However, with some companies “there is not a clear delineation between the different internal entities that are charged to be on the forefront of addressing these issues,” Barye-Garcia adds.

For example, in many private sector firms, the corporate affairs division takes the lead in interacting with regulatory agencies and governmental initiatives that deal with socioeconomic policy. In some of these cases, the global security department could bring considerable subject matter expertise to the table, but the firm’s strategic planning has not yet reached the level where the two departments are integrated in these operations.

“The greater the participation of the global security function in day-to-day operational business decisions, the greater influence it will have in establishing company strategy and addressing the root causes of security instability,” Barye-Garcia says. He adds one caveat: the companies in question “must have the culture and appetite to be forces for change and to take social responsibility in the markets in which they operate.”

Hart Brown, senior vice president and practice leader in organizational resilience for HUB International, also sees reasons why security operations may be getting closer to the root causes of insecurity, at least in some instances.

Mature security programs sometimes become a major component of an overall corporate enterprise risk management (ERM) framework, Brown says.

In an ERM program, reducing risks is a strategic imperative. A subset of ERM is enterprise security risk management (ESRM), which focuses on the mitigation of physical and cybersecurity risks from both strategic and operational perspectives.

In this context, addressing root causes can be strategically effective, because the problem is treated before it flowers into various threats. “The closer a risk can be mitigated to the actual root cause, the more effective the countermeasures are,” Brown says.

Traditionally, humanitarian or development groups were the ones treating root causes such as resource scarcity and poor education. But addressing these issues can also be thought of as building resilience, which has a place in some security programs.

“If the potential efforts to address root causes are viewed from the lens of enhancing resiliency rather than humanitarian or community development, there is a significant role for security to play,” Brown explains.

To illustrate, Brown offers the concept of making connections between the personal resilience of an organization’s staff to the resilience of the overall company to the resilience of the community where the firm is based.

Company staff may build resilience by providing educational and support services to the community. These services can boost resilience in several ways: they might reduce the potential impact of an event on the community; they might bolster the company’s reputation and increase company loyalty; or they might also build up staff skills in providing services that could prove useful later.

However, the IEC study also found that many organizations need more education on root cause issues. In the survey, 70 percent of respondents said they either strongly agree or somewhat agree with the statement, “my company’s board needs a better-informed understanding of the underlying causes of insecurity in the country where I am based.”

Brown sees this need as well, especially when looking toward a future with the potential for increased instability, and the potential costs of such on companies.

“There is an enhanced need to understand the root causes, at both a micro and macro level,” he says.