EP Skillsets: Why Elevating Leadership Skills will Protect your Business

I’m standing in the small office of the squadron leader, waiting with a group of my peers for the announcement of admission to a military academy. The squadron leader grunted: “…and those of you that weren’t accepted, go back to your room and figure out why you weren’t.”

This was an impossible and stupid task. Every applicant was a top performer. This was the last step, yet many candidates were left behind in the process. Everyone in that room wanted to know why some succeeded and others did not, but answers were not to be found among the rejected. Only the squadron leader knew but he would not tell us; he wasn’t the caring type.

SponsoredInside the Shadows of Alt-Tech Social Networks: The New Haven for Threats Against ExecutivesIn recent years, criminals and fringe groups have started moving to a growing collection of “alt-tech” social networks. And as a result, these communities have become breeding grounds for doxxings, false rumors, and violent extremists – posing a serious risk to executives and high-ranking employees. So how do protectors respond to this threat? |

The squadron leader was known by his colleagues as a guy who should be deployed only in case of an emergency—like the fire-fighting tool in a box that says, “Break glass to use.” What they meant was while he had his merits as a warrior and demonstrated excellence in tactics, he had shortcomings as a leader of an organization in peacetime. Although he had passed through military academies himself, he did not pick up any of those leadership skills. Maybe his personality was a part of that; he pursued in difficult times when managing people wasn’t prioritized.

To become a true leader, however, you need to be excellent at managing operations and strategy—in both peacetime and wartime.

But promotions to become a leader based on individual tactical skills alone happen often and are a general occurrence in the job market. The best-performing nurse is rewarded with a new position as the head nurse. The hard-working mechanic becomes the team leader, then the workshop manager or purchasing manager. The most dedicated security officer is promoted to security manager.

The common belief that leadership and organizational skills develop from the ability to perform well individually, in a profession, is problematic. Performing the best in a profession is not validation that you are capable of leading others in an organization.

EP leaders must understand the importance of further training and well-being among agents.

Three obvious explanations are behind why this occurs, though: management roles often earn a higher salary, the belief that leadership is an innate talent, and lastly, a missing tradition of further or higher education and training, typically among ”blue-collar work.”

The jobs within the security profession—and executive protection (EP), sometimes called close protection (CP), especially—are modern blue-collar work. The security market is full of EP companies and founders. The U.S. state of Florida, for instance, has about 26,000 registered armed security officers. And there are more than 15,000 CP SIA license holders with 194 different nationalities. With such high numbers of participants, it’s likely thousands of them are providing EP as a founder or a contractor setting up details. Most likely, many of them also went from working tactically as agents to driving operations and strategy as leaders.

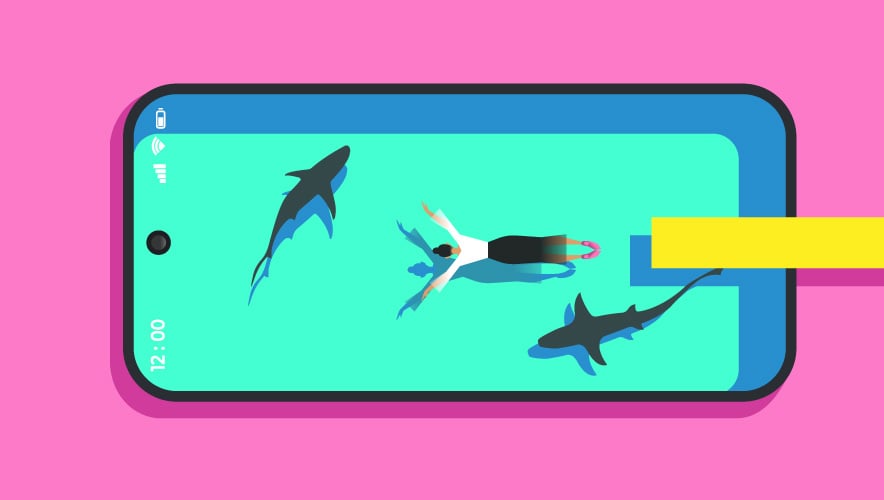

What do we overlook when we assume a successful EP agent will automatically transition to becoming a successful business owner or manager? It sends the message that leadership requires no skillset of its own, and the strengths of an organization are not fully understood.

This may be counterintuitive for some. They might ask: “How can an organization save the life of a client? Isn’t it about hard skills on the field and being tactical?”

Well, obviously EP is the business of saving lives for money. But it’s naïve to believe escaping an incident with the life of a client intact is enough; especially if the EP business is active in non-regulated markets or in countries lacking legislation and standards governing EP work. In case of an incident, the company and the founder might be held accountable. For that reason, EP companies and founders should be even more concerned about having the right leadership skills represented and a solid, durable organization constituting their operations. And EP agents should ensure these aspects are in place before they accept a job at a company.

The Transition Gap

The transition from agent to manager can be explained simply by looking at the responsibility for the different stages of a job task. An EP agent is generally working in a tactical position, perhaps assigned from one detail to another, with little ability to decide and prepare for what’s coming next. Even if advances should be part of the operation, agents are very often in the hands of the client and handle unknown—and unpredictable—situations. An EP manager is driving operations, trying to make them more predictable and smoother for agents in the field, while also managing client relationships and the back office.

The big leap to become an EP leader is where the gap occurs. These leadership roles require an understanding of the value of strategic work; assigning knowledgeable people to run the company, not only details; and setting up a structure that fosters an environment where people become part of an organization with shared goals, towards a company that withstands incidents and unexpected events.

EP leaders

Typical tasks for EP leaders are planning for the overall business and setting the strategy of the company. Preparing and planning involves investments in the workforce, in devices and systems directly supporting operations, and in knowledgeable people to manage the back office, boosting the exposure of the business so it continues to grow.

In reality, this position is about finding and hiring new personnel, managing and caring for the workforce, planning for and enabling vacations, rotating jobs, and furthering training for employees to ensure a sustainable and motivated workforce.

Investments in devices and systems supporting the operations may seem like a natural skillset for leaders to have; however, understanding the return of investments (ROI) on a salary system or an accountant who ensures timely and accurate payments, invoices, and tax payments, is equally important and perhaps not as apparent.

Growing the business with new clients, in new markets, while caring for existing clients and offering them extended services requires different skillsets and investments. The first is about attracting attention, the other is about keeping the attention of the clients. The biggest game changer for the business is the transition from ad hoc services to long-term contracts developing initial contracts into a predictable revenue stream.

EP operations, the day-to-day work, is perhaps not managed by an EP leader—that may be more the work of an operations manager. The EP leader might oversee operations and deliveries over time and the planning of performance, but most of all the leader ensures there’s a consensus on how to run operations.

To protect the company, the client, and the employees, operations should be run by people with a shared understanding of risks, procedures, mandates, and orders. These should be followed by clearly communicated processes controlled by rules, regulations, and policies; and all this should be prepared for and followed up through protocols.

An EP leader is liable for having regulatory documents and standardized work processes in place. And the EP leader must ensure employees are compliant with supervisory documents and enforce the company’s values and ethics. Equally important is the company’s compliance with external supervisory bodies such as finance, insurance, licenses, regulations, and business contracts (MSA), directing the scope of work and performance set by the clients. This will secure and protect the operation—and the people involved—before, during, and afterwards.

The management of employees is a huge task for the EP leader. Agents, the human capital, are the most valuable asset of the company. And developing from team leader managing elementary needs such as breaks, rest, and food to recruiting and retaining agents is a big step.

Finding good candidates, assessing them, and on-boarding them are not easy tasks. They cost both money and time. Agents must meet the right prerequisites and understand the requirements to conduct operations. EP operations can continue around the clock and be both intensive and energy draining over time. Simultaneously, EP work can be modest, routine, and uninspiring. Demanding compliance and motivating the same workforce can be contradictory, therefore adopting a deliberate leadership style is key to guiding the management of agents through operations. EP leaders must understand the importance of further training and well-being among agents, and perceive personnel as an investment.

Creating Organizational Value

Altogether, creating a structure and an organization with these attributes requires leadership skills, EP knowledge, and business acumen. Without these skillsets in place, incidents can occur that could comprise the safety of clients and agents in the field.

For instance, if the EP company is involved in a traffic accident that harms or kills a client there will be consequences. This might especially be the case if there is a lack of documents directing the renewal of licenses, requirements for rest and duration of work shifts, protocols for worked hours, and further training. Also, policies governing work-life balance, conflicts in teams, decision making, etc., will play a role in the outcome of the accident. Potentially, this could contribute to or result in a business interruption for the EP company, putting it under strain and damaging the company’s reputation.

Depending on the level of harm and the client, it could also become a media event that further damages the credibility and effectiveness of the company—a major turnoff for future clients and recruitment of prospective agents.

So how can this leadership and organizational structure be achieved? One suggestion is to hire managers and support functions. These individuals don’t need to be proficient in evasive driving, shooting guns, or close combat—they need to understand the need for these skills, how they are qualified, and how to employ people who have them. Managers should be proficient and understand the bigger picture of an operation. That means they are best at pulling the trigger of support for agents and the operations. Finding, assessing, and hiring EP leaders or other personnel should follow a standardized process which will increase accuracy and prevent discrimination. ISO 10667 is the standardized document governing assessment of candidates.

A good hiring process starts with creating a job profile, a description of the role, and the required set of knowledge and skills for matching a potential candidate with a role or recruiting a candidate to a company.

Within organizational psychology a well-known definition for attributes required to perform a job is Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other Characteristics (KSAO). It’s recommended to identify the job tasks and the four attributes for key roles to ensure that roles are clearly defined and filled in the organization. Yet the security business overall can be quite immature when it comes to the use of tests for a more accurate match between a person and a job task. Work sample tests have demonstrated a good correlation to work performance, as well as cognitive tests and personality tests based upon the Five Factor Model. These tests are more objective and reliable than other common measures used in hiring processes, like reference checks, unstructured interviews, job experience measured in years, and other personality tests such as Meyers-Briggs.

If hiring new leaders for the company seems like too expensive an investment, there’s an alternative: training. Management and leadership can be trained, because it’s a skillset obtained through knowledge and a bit of introspection—not an innate talent. Improve the team by mandating management courses and business administration courses. There are a variety to be found with legitimate organizations like ASIS International, LinkedIn, major universities, and more. The most prevalent leadership styles to look for when choosing a training program are Ethical Leadership, LMX (Leader-Membership exchange), and Transformational Leadership, all well researched with useful implementations for security practitioners.

Start your journey today to become a resilient business owner and a successful EP leader by adopting regulatory documents and a deliberate leadership style. It will pay off.

Jessica Fixelius is managing director of executive protection at Pinkerton, responsible for managing and coordinating key employee and HNW security globally. She has advanced degrees in psychology and is an experienced international security expert specializing in all aspects of HNW security. With military experience assigned to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in conflict zones to protect dignitaries and executives, and extensive experience in the corporate environment, she has managed numerous potentially high-risk security assignments.

© Jessica Fixelius, Pinkerton Consulting & Investigations Inc.