The Changed Nature of Civil Unrest: Lessons from 2020 in Philadelphia

Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was convicted of second and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter on 20 April 2021 for killing George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, while in police custody. For many, the Chauvin’s conviction provided some relief to a period of intense anger and frustration. For some, the healing process can begin; however, for others caught in the wake of peaceful protests that deteriorated to rioting and looting, the summer of 2020 remains an open wound. One example of a city on the path to healing through reform is the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

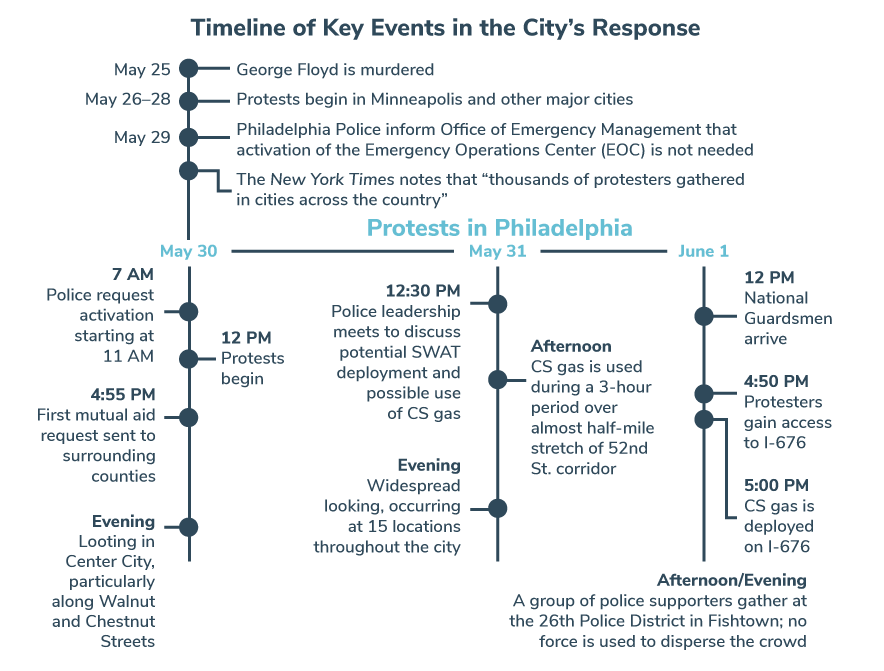

On 30 May 2020, the first in a series of large-scale protests began in Philadelphia. Civil unrest continued over the following week. Police responses to the mass protests included the deployment of CS gas (tear gas) and rubber bullets against protestors and civilians on 52nd Street in West Philadelphia and protestors on Interstate 676. By 2 June, 692 people were arrested, 72 police vehicles were vandalized, and 104 officers were injured or assaulted. The civil unrest in the Philadelphia cost more than $21 million, according to an independent investigation into the city’s response to the unrest.

It is essential to acknowledge the significant contributions and efforts of individuals and agencies across Philadelphia that responded to the civil unrest and professionally performed their duties and responsibilities in a dynamic, tense, and complex environment. Their efforts undoubtedly mitigated further violence and property damage; however, we must focus on the lessons learned from this experience if we want to prepare security operations for the new norms of civil unrest.

To quote Martin Luther King, Jr., “We must accept finite disappointment but never lose infinite hope.”

Investigating Missteps and Emerging Trends

On 4 June 2020, City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart announced that her office would conduct “an independent review of the City of Philadelphia’s operational and resource deployment and tactics during the civil unrest that followed George Floyd’s murder.” To conduct the independent review, the Controller engaged two firms: Ballard Spahr LLP and AT-RISK International. (Disclaimer: The author was involved in the investigation as part of his role with AT-RISK International.)

The investigators reviewed more than 1,700 documents provided by the city and interviewed more than two-dozen city employees. The investigators also analyzed the city’s past responses to significant events ranging from long-term and pre-planned events to spontaneous gatherings. Lastly, subject matter experts compared Philadelphia’s protest and civil unrest response, policies, and training to recognized authoritative guides, studies, and available research. The investigation produced 14 recommendations—many focused on updating the police department’s civil unrest and use of force training, policies, and protocols to respond to the new age of civil unrest.

The new norm is marked by increased national coordination of protest movements, looting caravans, a lack of willingness by local movement leaders to coordinate with law enforcement before and during protest events, and the participation in protests by “leaderless” groups, according to a 2018 report from the Police Executive Research Forum, The Police Response to Mass Demonstrations: Promising Practices and Lessons Learned.

Today’s protest environment also includes infiltration by outside agitators and criminal actors with no relation to peaceful protest groups. Instead, infiltrators take advantage of the ensuing chaos for specific ideological or financial gain. The presence of outside agitators—in some cases paid and opportunistic criminals—drastically increases the potential for violence, looting, property damage, and police use of force incidents. Of the investigation’s five major findings, two involved increased and inappropriate force indiscriminately used on protestors and agitators, including improper use of CS gas.

Investigators concluded that police officers and commanders lacked the benefit of updated and enhanced civil unrest policies and training, including use of force policy and training specific to civil unrest. For example, training to traditional use-of-force decision charts is most appropriate for conventional police encounters with the public; however, it is ill-suited for blanket use during civil unrest events.

Today’s protest environment also includes infiltration by outside agitators and criminal actors with no relation to peaceful protest groups.

Today’s protestors often carry shields, signs with wooden handles, and other equipment that could be misperceived as an offensive weapon, which can lead to inappropriate or illegal use of force. Additionally, some states are open-carry states, and recent mass protests demonstrated the propensity for participants to openly display firearms. Thus, new policies and training should draw clear distinctions between police engagement and use of force in general and police encounters with the public during incidents of civil unrest, protests, and mass demonstrations.

Lessons learned from the Philadelphia experience can be used by law enforcement and the private sector to create and or enhance civil unrest emergency response plans to reduce financial and reputational harm. Private-sector stakeholders should consider two essential questions to guide civil unrest emergency planning, preparation, and response.

Can We Protect Our Property and Assets When the Police Are Overwhelmed?

The events during the summer of 2020 taught security professionals that planning and preparing to counter threats is a dynamic process and cannot be viewed through a traditional response lens. Civil unrest in North America and the intensity and tactics used by protestors and violent agitators alike have changed.

In October 2020, the Major Cities Chiefs Association (MCCA) released a report on the 2020 protests and civil unrest. The report identified that between 25 May and 31 July 2020, there were 8,700 demonstrations in 68 major cities in the United States and Canada. Of those protests, 574 involved acts of violence, rioting, and looting. The MCCA report identified more than 2,300 separate looting events, with a single looting event at a shopping mall resulting in over $70 million in damage. The civil unrest was also marked by violence, with a reported 624 arsons and more than 2,000 police officer injuries.

The protestors and infiltrators applied a wide range of tactics and weapons to disrupt police response, from laser pointers and paint used to blind officers to improvised fireworks, leaf blowers, and firearms, according to the MCCA report. Across the United States, many police departments found themselves overwhelmed by the violence and calls for service, leaving looters and vandals unchecked. Additionally, private business owners were left scrambling to assemble or hire security assets to protect their properties from looting and arson.

The Philadelphia investigation identified just how the city police department’s resources were exhausted during the first days of the mass protests in response to George Floyd’s murder. Looting began in a shopping plaza located in the Parkside section of the city. Looters targeted nearly every store in the shopping plaza, including a grocery store, a hardware store, and a bank. Although employees at the grocery store called 911 multiple times to request police assistance, the police never responded. As a result, when the store’s director returned the following day at 6:00 a.m., looters were still in the store, stealing and vandalizing the property.

In another incident, when the police attempted to intervene in the looting of a beauty supply store, an officer was severely injured when he was struck by the suspects’ vehicle in their attempt to escape. The car ran over the officer, breaking his left arm, ribs, scapula, and part of his backbone.

“The vandalism and looting following the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police will cost the insurance industry more than any other violent demonstrations in recent history.”

By the end of the first night of civil unrest, at least 13 police officers were injured, there were nine arsons, and four police vehicles were damaged, including two police vehicles that had been set on fire. The Philadelphia Police Department reported 109 arrests, including 52 for curfew violations and 43 for looting.

Witness accounts of the looting documented in the investigation’s final report described “police engagement as limited…with virtually no police presence in the area to deter the looters or to restore order.” Others told investigators that when police were present at looting events, “they refrained from engaging the looters.”

The Philadelphia experience—similar to the experiences of other major cities across the world in 2020—provide evidence that the private sector can no longer solely rely on the police to protect businesses during civil unrest. According to a report from Axios, “The vandalism and looting following the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police will cost the insurance industry more than any other violent demonstrations in recent history.”

Unfortunately, there exists a misperception by many that insurance will fully compensate businesses that suffer losses because of riots. A recent Forbes article argued otherwise, noting, “People who assume insurance companies will make every business owner whole are wrong.”

Beyond the immediate financial impact of damaged property and inventory loss due to rioting, reputational harm and lost economic activity negatively affect small to large businesses in the area, according to Marketplace. It can be argued that for some the costs are too significant not to consider alternate protective strategies. For example, one business owner interviewed during the Philadelphia investigation said that his “company hired private security to deter further acts of violence after the first night of civil unrest.”

The critical takeaway is that stakeholders should evaluate their company’s civil unrest emergency response plan (EOP) to account for the challenges presented by the scope, intensity, and violence of the new era of civil unrest. Important considerations for developing a high-quality EOP include local and nationwide intelligence and risk analysis capabilities; preestablished emergency guarding agreements; and functional annexes for evacuation, lockdown, lockout, sheltering-in-place, and recovery/continuity of operations. EOPs should include identified goals, objectives, and critical tasks before, during, and after a civil unrest incident.

Does Our Company Possess the Resources to Win the Open-Source Intelligence and Communications Battle?

The current landscape of unrest requires a willingness to adopt new policies and standards for emergency response, including the critical role of intelligence collection, analysis, and distribution can play in mitigating harm. Recommendation three of the investigative report noted that initial intelligence collection, analysis, and distribution failures in Philadelphia added to property loss and poor resource management despite sufficient availability of open-source intelligence (OSINT) to inform decision makers about the threats of looting and violence.

On 28 May 2020, the Delaware Valley Intelligence Center (DVIC) issued a report indicating that there were increased threats to law enforcement following the national coverage of George Floyd’s death and there were “calls for looting and acts of civil disobedience.” By 4:30 p.m. on Friday 29 May, the DVIC also reported a social media movement calling for protest and looting of Target stores across the country.

Furthermore, a review of social media posts published in late May by Philadelphia-based activist groups—including Black Lives Matter Philly and the Philadelphia chapter of the national Black Lives Matter organization—identified two different scheduled protest events in downtown Philadelphia. National news outlets, including the New York Times, had already reported the outbreak of violent protests in several U.S. cities, including Minneapolis, New York, Los Angeles, Memphis, and Atlanta.

Security stakeholders should consider their capacities to exploit available intelligence before and during a crisis event.

The information was publicly available, yet the lack of clearly defined civil unrest intelligence-related protocols left key Philadelphia stakeholders ill-prepared for what was coming. Protest groups and infiltrators did not have the same inefficient use of intelligence and communications channels; investigators found that looters “acted in a somewhat sophisticated manner, coordinating their efforts using social media and by listening to police radio to determine where the police had staged.”

Security stakeholders should consider their capacities to exploit available intelligence before and during a crisis event. Identifying real-time actionable riot and looting intelligence could help prevent, protect, or minimize employee injuries and financial losses. During civil unrest, proactive communication with the public is also noted as a best practice.

The Police Executive Research Forum released a report about communicating with members of leaderless demonstrations and winning the loyalty contest with protesters. The tactics described in the report account for the changing nature of mass demonstrations and include “developing relationships with known protest movement leaders to assist with connecting to more decentralized movements, the use of social media to convey positive messaging during protests, build rapport, and convey rules of engagement to protest groups.”

In summary, responses to civil unrest requires new approaches to emergency planning, assessment, response, and recovery. Technological advancements like social media have changed activism globally. As a result, groups that started as single-issue activists are using their platforms to influence business and public policy decision-makers. Therefore, stakeholders should consider enhancing civil unrest emergency response policies and strategies by focusing on four key capabilities:

- Ability to protect employees and property from injury and looting and damage, respectively, by identifying security companies capable of assembling protective details before a critical need develops.

- Ability to collect and analyze open-source intelligence to identify real-time actional civil unrest and organized looting intelligence.

- Ability to provide updated civil unrest training for both in-house and contracted security personnel.

- Ability to communicate with the public and organized protest groups before, during, and after a civil unrest event occurs.

The Philadelphia investigation identified a confluence of factors that contributed to the systemwide failures in the summer of 2020. However, the investigation found that the root cause of the failures was the city’s failure to sufficiently plan for the protests leading to insufficient manpower, ineffective response, communication, and intelligence failures. The Philadelphia experience serves as an impetus for change and caution to all security professionals that emergency response planning must be as dynamic as is the changing nature of civil unrest.

Mark Concordia is a detective sergeant (retired) and Certified Threat Manager with AT-RISK International. Concordia has more than 25 years of experience working to prevent violence in both the private and public sectors.