Evolving Biothreats

Chikungunya. Enterovirus. Cyclosporiasis. MERS. Ebola. Zika. Those are just a few of the outbreaks the United States has experienced over the past five years, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And that doesn't include the dozens of foodborne outbreaks or diseases affecting pets and livestock that spread across the country each year.

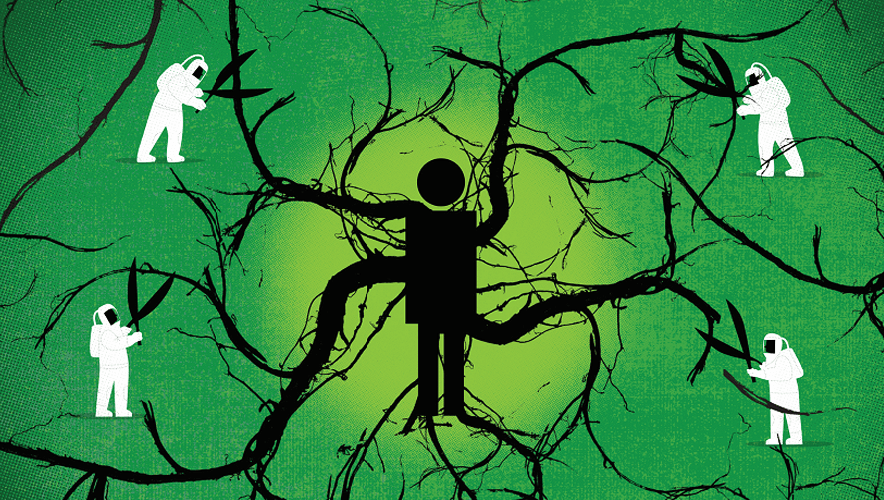

These diseases not only take a toll on public health, the global food supply, and the agricultural sector, but they can be a threat to national security, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Infectious diseases are spreading faster and emerging more rapidly than ever before, and nonstate actors continue to advocate for the use of biological weapons.

Despite being more than 15 years removed from the anthrax attacks that advanced the United States' biodefense posture, naturally occurring and manmade biological threats continue to pose a "catastrophic danger" to the country. But the national biodefense approach has not evolved with the emerging threats, according to a new GAO report.

"Biodefense is fragmented across the federal government, and we've reported in the past that there are more than two dozen presidentially appointed individuals with biodefense responsibilities," says Christopher Currie, director of emergency management, national preparedness, and critical infrastructure protection at GAO. Currie was the lead author of the recent GAO report, Biodefense: Federal Efforts to Develop Biological Threat Awareness.

GAO has reported on the agencies and programs that oversee the nation's biodefense for years, tracking programs such as BioWatch and laboratories containing hazardous pathogens. Currie acknowledges that the country's biodefense landscape is complex due to the number of agencies involved and the breadth of threats.

"Each federal department has its own appropriations, own congressional oversight, and frankly its own world of stakeholders it deals with," he tells Security Management. "It's very difficult to make decisions across all of those on priorities when they are so separated. And everyone is involved to a different extent."

The GAO report takes a detailed look at the role of each of the key biodefense agencies—the U.S. Departments of Homeland Security (DHS), Defense (DoD), Agriculture (USDA), Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and how they develop and report biological threat awareness.

"Part of the reason we did this was just to show and describe to people what is going on, because it's difficult to understand across all these agencies who does what and why," Currie says. "The goal of this was to get in there and understand behind the scenes what all the federal departments are doing to identify the risks and threats that would lead on to next steps of prevention and protection. That might inform what countermeasures you develop, what detection technologies you develop, and so on."

While each of the agencies plays an important role in managing biothreats in their sector, the lack of an overarching strategy makes it more difficult to get a well-rounded picture of emerging threats and how the agencies plan to respond.

"One of the things we talk about in this threat report is that clearly there's a lot of formal and informal coordinating and communication between these departments," Currie says. "The problem is, how does that translate into an overall prioritized strategy? That's where I think the efforts kind of stop, and it's vague what the government's overall strategy and goals are."

Currie points to the spread of Ebola to the United States in 2014 as illustrative of the lack of a united strategy. After a series of missteps at a Dallas hospital left one man dead of the disease and two nurses infected, the federal government called for procedural reviews and the CDC promised to deploy rapid response teams to future possible Ebola cases.

"You saw this with Ebola—the White House counsel tends to get very involved when these kinds of instances and crises happen. They immediately stand up these ad hoc groups to coordinate the response effort, but those quickly go away once the paranoia and panic dies down and we go back to the status quo," Currie explains. "That's a great example of why we're asking these questions about who's in charge. Is it CDC? DHS? The White House? Who's in charge of communicating to the public?"

GAO asked this question in a 2015 report on the fragmented biodefense enterprise, but not much has changed since then. The Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, which is made up of former government officials and academic experts and analyzes the country's defense capabilities against biological threats, also came out with a 2015 report condemning the lack of federal leadership in the biodefense sector. The panel's primary recommendation was for the U.S. president to appoint the vice president as the leader of federal biodefense efforts. "This is the single best action the Administration can take to resolve the continued challenges in biodefense," the panel states. "The ad hoc implementation of our other recommendations in the absence of this leadership will only result in more of the same uncoordinated effort."

The panel continues to call for implementation of its action items, noting the "limited progress" that has been made since the 2015 report. "The federal government could have—and should have—completed 46 of the action items associated with our recommendations within one year," the panel states in a December 2016 assessment of federal efforts. "In the year since we published the Blueprint for Biodefense, the government made some progress on 17 of these, but only completed two."

Currie says he has not spoken directly with the current administration on whether it intends to make any changes in how biodefense is approached, but notes that the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act requires the key agencies to develop a national biodefense strategy. Currie says he's optimistic that the requirement will encourage the DoD, HHS, DHS, and USDA "to actually do what we've been saying for a few years now." The strategy was due to congressional committees in September 2017, but as of mid-November Currie says the process was still under way within the government. GAO will review the strategy once it is available and determine whether it addresses shared threat awareness.

"I know they are working on it, clearly there is someone in the administration that's focused on it, but I don't know a lot about where this falls in terms of priority for this administration versus other threats like cybersecurity or countering violent extremism," Currie notes. "That's the part that is unknown."

Currie acknowledges that President Trump has proposed budget cuts within the different key agencies that may affect biodefense research and preparedness, but it is unclear whether Congress will approve those cuts. He points out that without an overarching strategy, it is more challenging to make sure the right agencies have the right funding.

"It does raise questions about how big a priority the biothreat part is for each of these agencies," Currie says. "What does the administration think about DHS's role in this versus what other agencies are doing? That's part of the problem with this, we really don't know how eliminating what one organization or department does will affect the entire enterprise because it's so fragmented."

Meanwhile, biological threats continue to spread, and there is no singular platform to track them all. The CDC and USDA websites each have different lists of foodborne outbreaks and recalls. The description of DHS's role in biological security is found under a "Preventing Terrorism" section and does not list any current threats or prevention activities. A search for DoD biological security efforts leads to an acronym-heavy webpage that was last updated in 2014. And, in other parts of the world, European Union member states are seeking funding to study the rapidly spreading African swine fever, which is infecting livestock, by declaring it a global health security threat.

"Ultimately, we've seen a lot of different strategies come out over the years about pieces of biodefense and surveillance," Currie says. "It's one thing to have a strategy, but you have to have the execution and implementation plan for the strategy. Departments have to be clear about what they are supposed to be doing, and there has to be some sort of accountability, and that's a big question: Who's going to be ultimately accountable and who are the departments going to answer to in actually implementing and executing the strategy? I'm hopeful that the strategy will address that issue, because without that it's going to be difficult across such a big enterprise to implement."

To read a response to this article,click here.