A New Mandate for the Modern Library

Visit any public library on a Saturday morning and odds are good that people won’t just be in line waiting to check out books. Instead, they might be trying a morning yoga class, learning how to use a 3-D printer, attending a club meeting, or getting help with their passport application.

Yes, the books are still there, and they are still important to public libraries’ missions, but libraries are looking for new ways to attract visitors who are looking for something more than the latest New York Times bestseller.

“That’s part of how the library systems are adapting to what’s needed,” says Larry Volz, chief of security for the DC Public Library System. “If you keep buying hundreds and thousands of books, and people just aren’t doing books, then you have to rethink that. You have to say, ‘What do people really want?’ They want places to meet; they want open spaces to talk.”

And this focus on creating a space where people are encouraged to come, bring a friend, and spend the day creates new challenges and opportunities for library security. Security Management sat down with Volz and the security team at the New York Public Library to find out how they’re partnering with library staff and first responders to address new concerns.

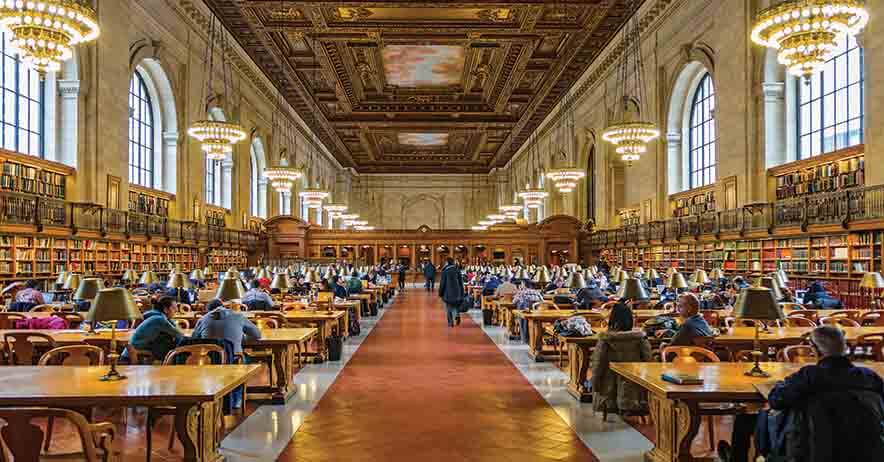

New York Public library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is an institution. Founded in 1895, it’s the United States’ largest public library system, with 88 neighborhood branches and four scholarly research centers serving more than 17 million people a year in three boroughs.

While it is home to millions of books, the NYPL also has historical collections that include Christopher Columbus’s 1493 letter announcing his discovery of the New World, George Washington’s original Farewell Address, and John Coltrane’s handwritten score of “Lover Man.” It offers 67,000 free programs to visitors annually, from author talks to art exhibitions to English classes.

Protecting this institution, its visitors, and its collection is a vast responsibility for Director of Security Services Tony Gonzalez and his security team of 60 proprietary employees—security managers, supervisors, and investigators—and 150 to 200 contract security guards.

“I have an excellent professional team, who have a combination of experience in law enforcement and then in working in private-sector security to become experts in navigating enforcement with customer service,” Gonzalez says.

The security team meets regularly with other library staff to help build relationships: the investigative team meets weekly with library managers, and security managers and directors meet monthly at networking meetings.

“We’re prideful in trying to build strong relationships with stakeholders because our philosophy is that security is a team effort—it doesn’t belong only to the security department. It also belongs to the other stakeholders: library managers, librarians, facility service people, communications, special events people,” Gonzalez adds. “Anybody who has staff membership and ownership can be considered part of the team.”

As a major public institution in New York City, the security team has partnered with the city when it has special programs using NYPL facilities. For instance, the city uses NYPL branches for its New York City ID Program, which was created by Mayor Bill de Blasio and is designed to give anyone who lives in the city the opportunity to get an official New York City ID.

The NYPL has also worked to build relationships and conduct tabletop exercises with New York City first responders, such as fire chiefs and watch commanders, because it’s critical to have decision makers involved. “Not the police officer or firefighter who’s going to respond, but their people who, once they’re on the scene, would be giving directions and making command decisions as to what next steps would be,” Gonzalez says.

Scenarios include active shooter, including one in which an armed intruder sets a fire. “We’ve tried to [make it] so that the training and the information that we get from these types of scenarios is as realistic as possible,” Gonzalez adds.

One unique aspect of these tabletop scenarios is a focus on preservation by including the head of the Preservation Department in these discussions.

“They’re the experts on–once the emergency is mitigated—how we can minimize the damage,” Gonzalez says. “They’ve been very proactive in working in conjunction with an outside expert on preservation and best practices.”

The NYPL Preservation Department “engages in discussions with the emergency responders, who were not aware of all the different treasures that are available at the library,” Gonzalez says. “After the tabletop exercises, we actually did a walk-through with them, and we gave them a special viewing of the treasures.”

This makes a major difference, Gonzalez says, because the emergency responders now have firsthand knowledge and have seen with their own eyes some of the artifacts and documents that, if damaged, would have “an impact on the present generation and future generations.” By doing the walk-through, first responders “become more passionate with their mission of safety and security,” Gonzalez adds.

The NYPL also works with first responders and its internal staff to plan for major weather events. Leading this effort is Donald Campbell, director of emergency management at NYPL, who updates Gonzalez on storms that might affect the library system and makes preparations for the storm itself.

Campbell liaises with the New York City Office of Emergency Management (OEM) and OEM Watch Command and is in constant contact with the National Weather Service should a major event be headed his way.

During Campbell’s first week on the job in September 2015, New York City was under a hurricane warning, and he had a crash course in prepping for the potential disaster, going through preparing for the crisis, notifying staff and keeping them safe, narrowing down essential personnel who would need to come to the library, keeping employees at home safe, and returning to normal services after the storm had passed.

As part of that process, the NYPL creates two emergency operations centers—one is the 39th Street location next to the NYPL’s main building and another is an offsite location outside of the flood zone.

To give those centers visibility into the NYPL facilities while a storm progresses, the centers receive feeds from the camera system, which provides views of each library. NYPL also has an e-alert system to update staff and keep them in the loop.

Staff expertise is derived from preparing for and weathering Hurricane Sandy—Campbell at New York City’s OEM and Gonzalez at a major college.

“We’ve experienced Sandy and know what to expect—to expect the unexpected,” Campbelll says. “We’re always thinking of that with life safety as the priority.”

Additionally, NYPL is developing command post exercises in case there’s a terrorist attack at one of its locations, given that its Stephen A. Schwarzman Building is the second most popular tourist attraction in New York City. In January, the New York Police Department (NYPD) worked with the NYPL to train staff on active shooter scenarios and safe evacuations to better protect the library, which is considered a soft target.

“We’ve taken a very proactive approach to try to mitigate something before it happens, going through these different scenarios,” Gonzalez says.

While this focus on terrorism may be extraordinary, the NYPL still has normal everyday library concerns that it needs to navigate, such as de-escalating situations with visitors.

One step the library security team has taken is transitioning from police-style uniforms to corporate uniforms. This has been beneficial, Gonzalez says, because often a police-like uniform would escalate a situation with a visitor who was upset.

Along with the change in uniform, the NYPL security team is focusing on communicating more effectively to help de-escalate situations. Campbell recently attended a training session, called “Dealing with Conflict,” which is designed to equip all NYPL staff with a consistent and useful framework to make every encounter with people the safest it can be.

NYPL trainers are certified by the Crisis Prevention Institute in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, following a vetting process by NYPL’s director of training, Craig Senecal. The institute trained and certified staff representatives from various departments in the NYPL to teach the content to all staff. Along with initially certifying NYPL staff, the institute also provides support materials and updates to the training, Gonzalez says.

The training incorporates verbal judo, which teaches trainees to use words to prevent, de-escalate, or end an attempted assault. The technique was initially used by law enforcement in the military.

The training is conducted in a classroom environment and begins with an introductory foundation course followed by an advanced training module on dealing with the challenges of mental illness in the workplace.

The training is conducted through lectures that incorporate a PowerPoint and scenario training. The types of scenarios vary, but generally deal with violations of the NYPL’s rules and regulations, Gonzalez explains. Issues such as uncooperative patrons, defiant employees, and violent outbursts from patrons are also addressed. These scenarios were chosen based on reviews of NYPL incident reports, which revealed which current incidents could be incorporated into the training.

“Generally, it is up to the instructor to use his or her experience at the library to introduce a scenario to discuss in class,” Gonzalez says. “The training provides tactics to deal with each of the selected scenarios, with the ultimate goal being that the student will be able to reduce tension in a conflict situation.”

For example, one key aspect of the training is teaching staff what tone of voice they should use when they address individuals and when to engage other departments or the police.

“Our department is not a sworn department—we don’t have any tools besides our capacity to verbally communicate,” Gonzalez explains.

Also crucial to the training is teaching security staff and librarians when to alert and bring in other stakeholders to help handle a situation. For instance, if a patron seems agitated because a security officer is engaging with them, the training teaches officers how to know when to bring over a library manager to speak with the patron and hopefully de-escalate the situation.

“It’s just being able to work together to communicate effectively to treat each patron with dignity and respect, no matter how volatile the situation may start to become,” Gonzalez says.

And if the library manager and security officers are unable to de-escalate the situation and it turns into a physical altercation, then they’re taught to contact the police. Or if it’s a situation where someone is having a medical issue, security officers and library managers are instructed to call 911 or the fire department.

“It’s just learning a broad skill set of handling everyday situations that may have the potential to escalate,” Gonzalez says.

That training is now being rolled out to various stakeholders within the system, starting with senior and middle management staff. The NYPL is surveying the initial participants to gather feedback to help fine tune the training, with the goal of delivering it to all staff and providing annual workshops.

“Eventually we want to train every single individual who has contact with the public with these strategies and with these skill sets,” Campbell says. “We want everyone on the same page and sending the same message.”

DC Public library

Congress created the District of Columbia Public Library System (DCPL) in 1896 “to furnish books and other printed matter and information service convenient to the homes and offices of all residents of the District,” according to the library system’s website.

The library system’s offices were previously housed at various locations, but in 1972 the Martin Luther King (MLK) Jr. Memorial Library opened in the heart of Washington, D.C., and became the new headquarters facility to connect the 25 other branches within the system.

The 400,000-square-foot building, constructed of matte black steel, brick, and bronzed-tinted glass has seven levels. These levels house public service areas, meeting rooms, exhibition space, administrative services, and the DCPL’s police department. “The brain is at MLK, but the heart and lungs are out in the community,” Volz says of the system’s design.

That system serves the approximately 650,00 residents of Washington, D.C., plus the hundreds of thousands of residents of nine surrounding counties who can get a library card, for free, to check out materials and participate in events at one of the system’s branch locations.

This means that the DCPL is under a constant renovation process to improve its services and better serve the communities its branches are located in, says Volz, who joined the system as chief of security in 2014 from the University of the District of Columbia.

“I am new to libraries. I am not new to police work,” Volz explains. “So when I came here, I actually started asking questions, and I learned so much about libraries—how libraries are changing because they’re a very important source of information. They’re a place for people to meet, and that’s how we have to gear our libraries.”

Aiding in that goal is the DCPL’s own special police officer (SPO) force, which Volz oversees. All officers—he declines to say the specific number—are armed and have powers of arrest, functioning as a police department within their jurisdiction of the library system.

“It enables you to do a lot more things—if you need to take more serious action, you can,” Volz explains. “You don’t have to call Metropolitan Police, but that is an option if we need backup—which is very, very seldom.”

SPOs are stationed throughout the system at its busiest branches. Other SPOs rove the system, making regular stops at branches and responding to requests for assistance when an incident occurs.

Because SPOs aren’t stationed at every branch within the system, they work closely with the librarians who identify and respond to problems.

“Our first level of people who take care of problems are the librarians,” Volz says. “They handle 90 percent of any possible issues we have.”

To prepare librarians to respond to those problems—ranging from a loud visitor to an emergency situation—they receive verbal judo training to teach them how to interact with visitors, just like the NYPL staff.

“It sounds rather aggressive, but it’s not,” Volz explains. “It’s a really good program because it teaches you how to deal with people…how to introduce yourself and talk about what the problem may be.”

This is beneficial for librarians because some visitors to the library may not be aware of what the rules are in the library, so it teaches librarians how to inform visitors without escalating the situation.

One common scenario is when visitors fall asleep in the library, which is not allowed. Using the verbal judo training, a librarian who sees someone sleeping will go over to the person, check on him, wake him up, and tell him he needs to stay awake because sleeping in the library is against the rules.

If the individual continues to fall asleep, librarians are then encouraged to rely on the SPOs to intervene. “We’re the backup,” Volz explains. “We handle the situation when it gets out of hand, or if the librarians can’t handle it, or someone just needs some more explanation.”

In the case of someone continually falling asleep in the library, SPOs are taught to address the person, ask if anything is wrong or whether there’s something the SPO can help with, and then recommend getting up and walking around for a while to stay awake.

This process helps ensure that visitors know what the library’s rules are—and that the rules are enforced without incident.

Another common problem that librarians are taught to handle during verbal judo training involves a visitor who becomes unruly or overly loud, disturbing other visitors in the typically quiet library.

“We get some people who sometimes get a little disorderly, they may not be happy with a service they got or may not understand a service they got, and the librarians are the ones who handle that,” Volz says. “If that reaches a point where it gets a little too loud, we normally get called and we’ll come in and say, ‘Listen, let’s try to sort this out. In the meantime, you need to hold it down because you’re really disturbing the other customers.’”

After the success of the verbal judo program, Volz says the next step is situational awareness to make sure librarians know how to handle themselves in case a hazardous situation occurs—such as the fire alarm going off.

Using video training and onsite training for staff, librarians are taught proper procedures through a program called “All Hazards,” Volz explains. “To say this is how this happens, this is how this works, and this is what you should do in case this occurs.”

Volz started the program at his previous employer—the University of the District of Columbia—for staff members and new students to teach them about the security department and what to do in an emergency.

Volz and Patrick Healy, the DCPL risk manager, conduct the training in an hour-long lecture. The training gives an overview of the police force and some of the hazardous situations that may occur at the library—such as a fire, a gas leak, an earthquake, or an active shooter.

Attendees are then given basic instructions on what to do in each scenario, focusing on sheltering in place or evacuating the building. The information is broken down “in a really simplistic manner,” Volz says, because “it’s unreasonable for a person to carry around 15-inch manuals of all the things that can go wrong.”

Patrons are typically alerted to whether they should evacuate or shelter in place by an alarm or announcement over the library system’s public address system, which Volz says will identify the emergency. For situations where staff and library patrons would evacuate—like a fire or gas leak—Volz instructs training attendees to grab their belongings, lock their office doors, and leave the building by a known route.

For situations where staff and library patrons would shelter in place—like an earthquake—Volz says he references the 2011 5.8 magnitude earthquake that hit Washington, D.C., and caused major damage at various locations in the city.

“I like to personalize the training to the audience and tie it in with things that I think they will know,” Volz explains. Many library employees either worked at the library or lived in the area when the earthquake happened, so Volz discusses what happened and how library staff should respond should an earthquake occur again, such as sheltering in place underneath a table to prevent objects from above from falling and crushing them.

Volz has also begun to include active shooter training in “All Hazards” as part of a new focus on securing soft targets. Attendees are encouraged to use the “Run. Hide. Fight.” model and to do what they feel most comfortable doing in an active shooter incident.

“We focus on, if you’re going to run and need to get away, here are the things you should consider before making that decision,” Volz explains, such as thinking about the route to take to exit the building quickly while bypassing a gunman.

Volz also encourages employees to regularly take different routes through the library to get to their destination to teach themselves varying routes they could use to evacuate the building.

“You should be taking different routes constantly because you never know what you’ll see and then if there’s a problem, you’ll know a different route you can take to get to your destination,” he explains.

Approximately 40 percent of MLK library staff had received the training at the time Volz was interviewed, and it had an 80 percent approval rating based on employee surveys. Volz plans to work with Healy to roll out the training to the rest of the library branches and include it in new employee orientation.

All of this training goes back to the idea that libraries are adapting to the modern era where people want to come to the library not just for the books, but to meet people and participate in activities in a safe environment.

“Libraries are geared towards what their communities’ needs are,” Volz says. “The library attempts to meet community needs, and if we do that, then we’re doing a great job.”