Pink: Be Intentional with Your Timing

Daniel Pink’s keynote message yesterday, “How to Make Time Your Ally and not Your Enemy,” can be distilled down to three main points:

- Our cognitive abilities don’t remain static during the course of the day.

- These daily fluctuations are more extreme than we realize.

- The best time to perform a task depends on the nature of the task.

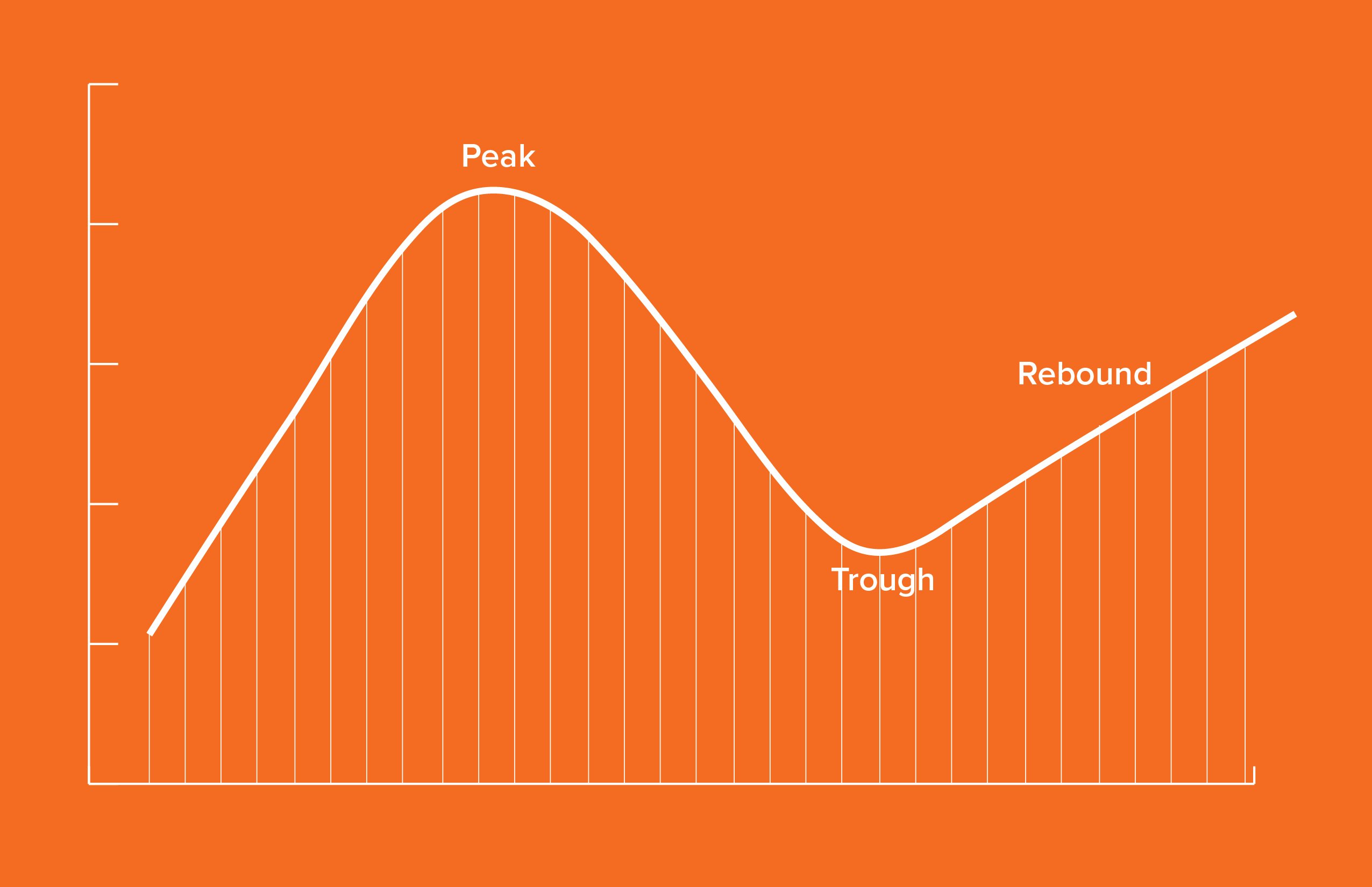

The Peak, the Trough, and the Rebound

Pink’s research took him to study after study that yielded a similar pattern. Everybody has a rhythm to their day, and it looks like this:

Each day has three distinct phases, and for most people, it builds to a peak, tumbles to a trough, and rebounds. Everybody, everyday, experiences these three phases.

In his presentation, and in his book, When: The Scientific Secrets to Perfect Timing, Pink cited dozens of academic research studies in a variety of fields that illustrate this pattern. One example examined hundreds of millions of tweets using artificial intelligence. The study concluded that in their tweets, people are happier, more upbeat, and more positive in the late morning to early afternoon and are decidedly less happy and more negative in mid-afternoon before rebounding as evening approaches.

The same pattern emerges in other settings. An analysis of thousands of pages of earnings calls corporate executives have with investors yielded a similar positive (in the morning), then negative (in the afternoon), emotional curve. The study showed real-world consequences as a result: Companies that held afternoon calls had real, if temporary, negative effects on their stock prices compared to companies that held the calls in the morning. Another analysis with critical real-world results found that hospitals make more mistakes resulting in worse patient outcomes when procedures are performed in the afternoon compared to procedures performed in the morning.

Chronotypes

The next layer to understanding this pattern is determining what time of day this means for yourself and the people you depend on. Pink lumps people into three categories, or chronotypes:

Larks: The early risers—people who start their day at 5:00 or 6:00 a.m. without an alarm.

Owls: The opposite of larks, these people stay up into the night and wake up several hours later than larks.

Third birds: The people in between larks and owls. Most people—approximately two-thirds according to one study—are third birds.

For larks, the peak is going to come in mid- to late morning; for third birds, a couple hours after that. The peaks are followed by noontime or early afternoon troughs and a rebound stage.

For the one-in-four people who are owls, the pattern is different. The research shows that when they get going in the late mornings, they start with a state of mind most akin to the rebound phase. The rebound is followed by a trough, and then they hit their peak in the evening or even late night. Why this is important is the next and final layer of understanding the importance of chronotypes.

When to Do What

Certain tasks are better suited for different phases.

“During the peak, that’s when we are most vigilant,” Pink explained in the session. “Vigilance means you’re able to bat away distractions. That makes peak the ideal time to do analytic work… work that requires heads down focus and attention: analyzing data, writing a report, carefully going over the steps of a strategy.”

Yan Byalik, CPP, is the security administrator for the City of Newport News, Virginia. He manages a team tasked with protecting the city’s critical infrastructure and serves on numerous city multidisciplinary working groups, providing security input on major initiatives such as mass vaccinations, election security, and special events.

For Byalik, one of his morning tasks—a task he undertakes when he is on the upswing—is reading shift reports. You may think that’s not the best use of time when you are on the upswing heading to your peak, but not so fast. Pink said the perfect time to do analytical work is peak time.

“Yes, reading shift reports can be really mundane,” Byalik says. “But I have come across some things reading those reports that are super critical. Maybe somebody missed something or didn’t tell us about something, and it could have resulted in a lawsuit or some kind of critical failure for the city if it wasn’t discovered and managed properly. That situational awareness that comes from reading those reports is pretty high on my priority list.”

Again, for most people, the peak is late morning to early midday. For owls, it comes much later.

So, is the rest of time just garbage time? Fortunately, no—the rebound turns out to have a different, but no less important feature.

In the rebound “our mood is up and our vigilance is down,” Pink said. “That’s a really interesting time. It’s an ideal time… for what’s called insight work, …work where you are iterating new ideas, solving nonobvious problems, where you’re seeing around corners, where you’re brainstorming.”

The trough? Well, that is pretty much garbage time.

“It’s a terrible time of day,” Pink said. “There are huge decrements in performance across a whole range of tasks. …So what you want to be doing is doing as much of your administrative work as you can then: answering routine emails, filling in your expense report. Things that don’t require massive brainpower or creativity.”

For Byalik, this is an ideal time to chase down and complete the random tasks that security is continually asked to do. For example, a staff person whose car was scratched in the parking lot may ask security to review video footage to see if anybody can be seen lingering next to the car. Or a manager will ask if one of their staff is leaving early.

“It’s not that these tasks are unimportant, because they are important,” Byalik says. “But these are not matters vital for public safety and they aren’t critical security tasks.”

Security, of course, like hospitals and a host of other sectors, cannot afford any garbage time. As session host Charles Alcock, senior editor with Aviation International News, put it: “We can’t just say, ‘Go away risk. I’m in a downtime.’”

Byalik illustrates this in stark terms. “A message we reinforce with our officers regularly is that their job is inherently dangerous. There are people out there that want to kill them,” Byalik says. “We emphasize with them that they are not first responders. They are zero responders—they are already there when critical events occur. If they fall asleep or are not paying attention, they’re not just jeopardizing the facility, they’re jeopardizing their own health and safety.”

In When, Pink noted that this garbage time is marked by “sloppy logic,” “dangerous stereotypes,” and “irrelevant information”—your basic recipe for security disaster. But all is not lost.

Breaks and Checklists

Perhaps the most important message is just understanding and accepting this natural shortcoming so you can plan your security procedures and processes around it. As a security leader, it is probably worth spending some time in your peak time and in your rebound time to contemplate how you can help your staff be as vigilant as possible in the garbage time. In the keynote, Pink offered two places to start.

First, embrace the magical restorative powers of the break—and preach it religiously to your teams.

Here’s a helpful rhyme from When: “Vigilance breaks prevent deadly mistakes.”

“We have gotten breaks totally wrong,” Pink said in the session. “We have completely undervalued breaks. I used to believe that amateurs took breaks and professionals didn’t. One hundred and eighty degrees wrong. High performers in every realm are intentional and take breaks. Breaks are part of our performance. They are not a concession. The way to get more work done and better work done is to be systematic and intelligent about breaks.”

Pink offered the following advice when considering how to be intentional about incorporating breaks into your routine, or the routines of your staff.

First, something beats nothing. Doing any kind of systematic break provides benefits. Pink said he incorporated a simple 20-second break once every 20 minutes into his routine where all he does is focus on an object outside his office window.

Second, moving breaks beat stationary breaks. The benefits of doing just about anything besides sitting still for hours are well documented. Adding physicality to your breaks—from a quick walk to busting out five or ten pushups—is a double-winner.

Next, social beats solo. Humans are social creatures—even introverts, maybe especially introverts. Interacting with someone in a nonwork way stimulates us and gets us more prepared to focus when back at work.

Fourth, outside beats inside. “Breaks in nature, even in an urban area…are more restorative than breaks inside. There’s some incredible research on that,” Pink said.

Finally, a fully detached break beats a semidetached break. Taking your phone to a different room and checking your email is not a restorative break.

The other technique Pink championed is the idea of using checklists. In the earlier example of hospitals making more mistakes in the afternoon than in the morning, one of the most effective solutions for decreasing the prevalence of afternoon mistakes is the rigid use of checklists.

Security has long embraced the checklist as a vigilance reinforcer. When a checklist becomes part of a routine, however, it can quickly lose effectiveness.

“Through so much of this research, you realize how important it is to be intentional,” Pink says in a discussion with The GSX Daily prior to his keynote. “You realize that we sleepwalk through things. And when you get into a groove, you can end up perfectly walking through the seven steps of a checklist but it’s no longer effective because you weren’t really paying attention to each item on the list and intentionally checking it off. So, you need some kind of hygiene for the checklist. You have to explicitly say, ‘We’ve used this checklist 25 times now, what’s working and what’s not working?’”

An important part of checklist hygiene is insisting on a culture where everybody is empowered and expected to hold others accountable to the checklist, and, from frontline security to managers, everyone is expected to analyze the effectiveness of the checklist and offer ideas to improve it.

At the city of Newport News, each posting has standard operating procedures (SOPs) that are unique to that facility and that post. They incorporate checklists and security reports. In some facilities, they use the equivalent of a technological checklist: officers on patrol push sensors throughout their route.

A Security Culture

Much more important than sensors or checklists, Byalik stresses the importance of the type of culture Pink described.

“You have to build a safety-sensitive culture in your team,” Byalik said. “And you have to lead from the front to make that happen. I try to be out and about as much as I can. I interact with our frontline officers regularly. They all know me. It’s important that I’m not some random suit sitting in an office somewhere.”

When an incident occurs, Byalik regularly shows up as a backup on the scene, as does his security leadership team.

“It helps to build that culture when I’m there side by side with the officers,” he said. “While we’re there together, we can immediately do a hot wash. I might notice that the officer turned his back on someone, and I can ask if it was an intentional action. And I’ve had officers point out actions I’ve taken. You get stronger when everyone knows these sessions are safe, that they can speak up, that they need to speak up. And that only happens if you’ve built a culture that encourages it.”

After presenting his three key findings, Pink concluded his keynote with three pieces of advice:

- Be much more deliberate and intentional about scheduling individual and team work. Move analytic tasks to the peak, administrative tasks to the trough, and insight tasks to the recovery.

- To protect vigilance, especially during the trough, use checklists and ensure that you make breaks a systematic part of your daily schedule.

“I would say that security is a very dynamic industry,” Byalik concludes. “There’s a lot of ebb and flow. There are daily routines, weekly routines, and monthly routines—there are numerous cyclical operations. As threats and threat environments change, as new technology comes out, bad guys come up with new ways of attacking our stuff, and we come up with new ways of defending it. Policies, procedures, routines—they all change in accordance with this ebb and flow.”

Scott Briscoe is the content development director for ASIS International, the publisher of Security Management—the parent publication of the GSX Daily.