The Calculus of Catastrophe

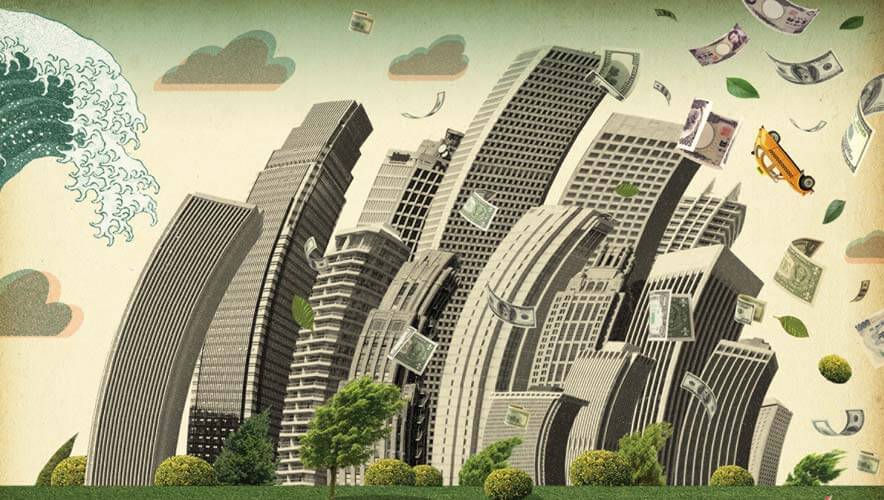

Cities are often cited as one of civilization’s greatest achievements. And their popularity continues to increase around the world, as more people are living in cities than ever before.

As a result, these vast urban areas have become concentrated wealth and productivity centers. The London region, for example, now accounts for 45 percent of the United Kindom’s economic output, triple the city’s 15 percent output rate in the 1960s, according to Cambridge University statistics.

This concentration makes cities powerful engines of business, but it also increases their exposure in the case of both natural and manmade disasters. If a major city goes down, much of a country’s economy will go with it. And with the world becoming more interconnected than ever, due to globalization and improvements in information technology, a disaster now has economic ramifications far beyond the country in which it strikes.

In an effort to get a handle on the economic consequences of disasters, researchers at Cambridge University’s Judge Business School and the Centre for Risk Studies conducted a risk assessment of 23 different types of catastrophic threats and the risks those threats would pose to the world’s 301 most productive cities.

The researchers used a tool called the Cambridge Risk Framework to assess the economic damage, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), that each disaster would cause over a 10-year period ending in 2025. The research was produced for the firm Lloyd’s, which used it to release Lloyd’s City Risk Index.

The 301 cities chosen for the index are the most productive ones, in terms of economic output, from the 50 largest economies of the world. The list includes the top 25 cities in the United States and the top 32 cities in China, the two countries with the largest economies in the world. Collectively, the 301 cities create half of the world’s GDP today, and are projected to produce two-thirds of GDP by 2025. All cities with more than 3 million in population are included in the list.

To evaluate potential catastrophes, the researchers went through 1,000 years of historical records and used the information to develop a taxonomy of threats. From this, researchers came up with the 23 most devastating threats from the known threat universe.

The most economically devastating threat is a manmade one—a market crash or banking crisis, which could cause lost GDP worldwide over the 10-year period. Next is interstate war, which could cost an estimated $500 billion in losses. Third is human pandemic, at $350 million in losses.

In general, manmade threats pose just as much economic risk as natural disasters. The research found that nearly half of total GDP risk is linked to manmade threats, including market crash, cyberattack, power outage, and nuclear accident.

The 301 cities in the index were ranked by vulnerability—the amount the city stood to lose from disasters. The three cities with the greatest loss potential are Taipei, with $201 billion in GDP at risk; Tokyo, $183 billion; and Seoul, $136 billion. Rounding out the top 10 most vulnerable cities are, in order, Manila, Tehran, Istanbul, New York City, Osaka, Los Angeles, and Shanghai.

The top threats, in terms of potential economic losses, differ for each city. For Taipei, Seoul, Manila, Osaka, and Shanghai, the biggest risk is from windstorms. For Tokyo and Tehran, it is an interstate war. For Istanbul, it is an earthquake. For New York and Los Angeles, it is a financial market crash or banking crisis.

Taking a broader view, the researchers found significance in the fact that a majority of the top 10 most vulnerable cities—and the top four overall—are Asian cities. This reflects a global economic shift in which economic power is shifting away from the developed economies of North America and Western Europe.

Moving forward, threats to world economic growth will be most significant in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Indian Subcontinent; the report shows that, collectively, 71 percent of the total GDP risk is carried by cities in emerging economies.

“This is a shift from historical patterns of loss,” the researchers write in their report. “Patterns of risk are changing—there is a shift in the geography of risk, so that future losses might be expected more in Asia and the developing markets.”

Although the general risk pattern may be moving toward Asia, recent natural disasters in the United States have ranked among the costliest in the world, according to another report, Annual Global Climate and Catastrophe Report, issued last year by the reinsurance company Aon.

The Aon report finds that, in the 10 years since Hurricane Katrina, the world has seen an annual average of 260 major natural disasters, with economic losses averaging $211 billion annually.

Since 1980, two of the five costliest disasters occurred at least partly in the United States. The Atlantic hurricane season disaster in 2005 was the second costliest disaster at $209 billion, and the 1988 U.S drought ranked fifth at $81 billion in losses. The costliest disaster was the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, which caused $221 billion in losses.

Moreover, the negative economic impacts of these disasters can linger for years, according to the findings of a third report, produced by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The NBER report, The Causal Effect of Environmental Catastrophe on Long-Run Economic Growth: Evidence From 6,700 Cyclones, found that after a cyclone strikes, a country’s economic growth slows a little bit in each of the next 15 years before stabilizing. This causes countries to be poorer for decades.

“This result reshapes our understanding of disaster’s human impact from a short-lived period of destruction and recovery to a multi-decade alteration of a country’s future,” wrote researcher Amir Jina, who coauthored the report along with Solomon Hsiang. “This means that we need to rethink disaster policy—focusing much more on the long-term.”

The most effective way to reduce long-term negative impacts may be to focus on resilience before the disaster occurs, the Cambridge research suggests. The study tries to estimate, in a large-scale fashion, how much the risk from disasters could be reduced through increased resilience and physical vulnerability improvements.

Researchers did this by assessing each city in two areas—the vulnerability of its physical infrastructure, and its social and economic resilience. Improvements made in both areas reduce risks, depending on the level of the improvements made. If all cities could reach the top level in terms of both infrastructure and resilience, then overall GDP risk would be reduced by 54 percent, the researchers found.

And the importance of resilience also applies to manmade disasters. For example, the financial reform efforts and regulatory changes—such as the Dodd-Frank Act that the United States implemented after the financial crisis of 2008—could make cites more resilient if another crisis occurs, explains Glenn Dorr, regional director of the northeast United States for Lloyd’s.

“You could argue that Dodd-Frank was a piece of resilience legislation,” Dorr says.