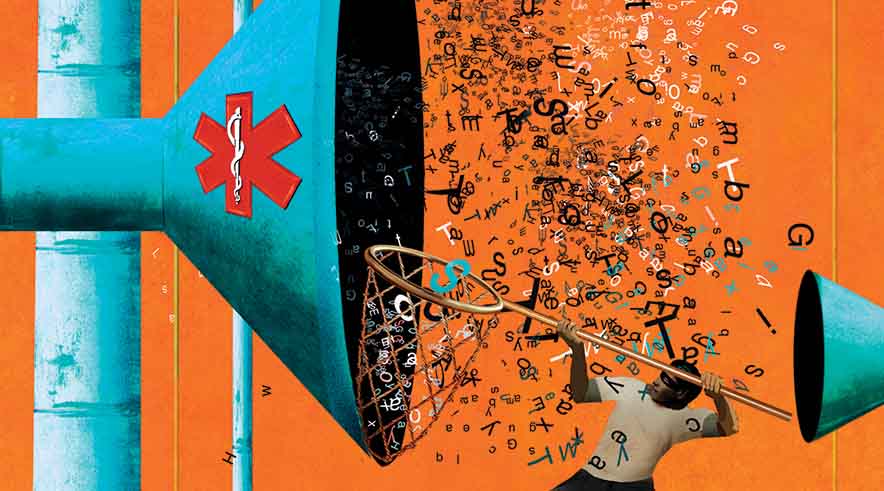

On the Record

Prolific American bank robber Willie Sutton stole an estimated $2 million from banks during his 40-year criminal career, a stunning sum for the early 20th century. When asked by a reporter why he robbed so many financial institutions, he replied, “Because that’s where the money is.”

That infamous line has since transformed into what’s known as Sutton’s law, a term widely used for training medical students. It means they should consider the most obvious diagnosis for an ailing patient before moving on to other possibilities. But for hackers, Sutton’s law ironically ties into the very reason they are targeting patient information from hospitals, insurance companies, and other medical institutions–patient healthcare information is extremely valuable.

On the black market, electronic medical records have sold for more than credit cards. According to a September 2014 report by Reuters, stolen health credentials were selling for around $10 each, which is 10 to 20 times the value of a credit card number.

“The bad guys know that personal information in a healthcare record is far better than stealing a credit card,” says John Prisco, president and CEO of Triumfant, a company that provides network protection services to businesses. “The problem with healthcare records is that they’re almost immortal, whereas a credit card has a shelf life of a day or even hours before it’s reported or shut down.”

Information contained in a patient’s medical record includes Social Security numbers, addresses, and dates of birth, in addition to medical details. “You can’t change your prior address; you can’t change your birthday; you can’t change where you were born. All those things travel around with you for your whole life,” Prisco explains. “If somebody’s going to try to take out a loan and they use your credit to do it, they’ve got a lot of information to substantiate that they’re you, even though they’re not you.”

Plans to protect patient information face numerous challenges, including cyberattacks, regulatory compliance, and interoperability.

CYBERATTACKS

Cyberbreaches in the medical industry are becoming more and more common. Between 2013 and 2014, healthcare companies saw a 72 percent increase in cyberattacks, according to a study by Symantec.

Perhaps even more stunning than the frequency of attacks is the sheer number of people affected. At the beginning of 2015, health insurer Anthem Inc. said that its database had been penetrated in an attack, compromising the personal information of some 80 million people. That overshadowed another recent hack, in which Community Health Systems suffered the compromise of 4.5 million patient records in late 2014.

Feris Rifai, CEO and founder of Bay Dynamics, a cybersecurity solutions firm, adds that healthcare organizations have made access to electronic medical records more convenient for patients, but in doing so have increased the attack surface. “By creating portals for patients…to do business in a modern era, they’re open to threats and there are definite risks that they’re susceptible to.”

Healthcare companies also suffer from using older systems or not keeping records up to date, notes Mike Spanbauer, vice president of research at NSS Labs. In the Anthem breach, for example, records of patients dating as far back as 2004 were compromised. “There are records systems and other applications which are not as modern as some of the more enterprise and productivity-centric platforms, meaning that they’re written on old libraries and, therefore, potentially susceptible to an attack,” he notes. “Healthcare, historically, has not invested as aggressively in IT and systems modernization.”

Mergers and acquisitions, which are common among healthcare companies, create another obstacle, as IT systems must be migrated, Spanbauer says. “If you’ve got multiple firewall types or disparate systems then it further increases the challenge.”

COMPLIANCE

Simply complying with the laws designed to safeguard patient information doesn’t mean that a company’s IT systems are secure, notes Rifai. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 is the standard for patient privacy, and “requires that covered entities apply appropriate administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect the privacy of protected health information (PHI), in any form,” according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. But that is simply a guideline, and additional measures must be taken, especially in training employees. “There are ways to check the box and be compliant, do the right things, but you need visibility across your organization,” says Rifai, who adds that the first place to look is at employee behavior.

In the Anthem breach in January of this year, hackers obtained the credentials of a database administrator and accessed the organization’s network. The hackers then slowly leaked out patient information over time, so there wasn’t a particularly alarming event occurring on that database administrator’s machine. To protect against such breaches, anomaly detection software can learn the normal behavior of an employee over time, then alert whenever anything is out of the ordinary, notes Rifai.

Training at the desktop level for end users is a critical piece of the puzzle in preventing an attack, he adds. One of the most effective methods is teaching employees to spot a social engineering campaign, such as a spear phishing e-mail. These messages are disguised to appear as if sent from a legitimate user, but when clicked on, they can download malware or serve as a foothold for attackers to gain entry to the network.

“If you’re doing it just to be compliant, maybe twice a year training, it just doesn’t have the same impact as when someone commits an infraction,” notes Rifai. “You educate them on the spot, you let them know that this should not have happened, and you get them at their desktop.” (For more on cybersecurity training for employees, see “Teach a Man to Phish” in the September issue of Security Management.)

Funding for security managers at healthcare companies is also an issue, notes Prisco, and he emphasizes the importance of getting C-level buy-in. “This is a cost to companies, it’s not a profit center, so you get the attitude from lots of companies that, ‘well if I’m protecting a million dollar liability, I’m not going to spend $10 million trying to protect it.’ So there needs to be a vast change in the way that the decision makers think about security.”

Security can counter such an argument by stressing that no dollar value can be placed on a company’s reputation, or that company executives are underestimating the liability. “It’s realizing that the million dollar liability may grow into something much larger and more permanent,” notes Prisco. “There are real tangible and measurable consequences [to cyber events], and I think the C-suite needs to understand these can become a lot larger than the liability they’re protecting.”

Rifai adds that the healthcare companies he works with recognize that they are a target, and they are taking important steps toward bolstering their security, including taking advantage of advanced tools like analytics and anomaly monitoring to catch threats before any permanent damage is done. “The days of hoping you’re not a target are gone. You have to do something about it,” he says. “I think there’s a broad recognition within the healthcare industry that that’s absolutely the case.”

INTEROPERABILITY

The move to digitized medical records means that criminal actors can now gain access to sensitive personal information more easily. But experts say the digitization of that information has also led to huge benefits for patients and healthcare providers alike.

Spanbauer points out the challenge that healthcare organizations face as they migrate paper-based records to digital ones, but also notes the benefits. “It’s a pretty considerable IT challenge when you’re trying to establish some sort of common record systems between providers and do so as securely as a banking system,” he says. “There’s a lot at stake and a lot to be gained if done right.”

For one, greater interoperability of electronic records would inevitably lead to better emergency medical care during disasters, says Barry Greene, chief information officer at the New York Guard—the state’s military defense unit. Greene has worked on providing IT services to healthcare providers during disasters such as the Haiti earthquake, Hurricane Katrina, and Hurricane Sandy.

“Interoperability of electronic medical records is still in its infancy,” notes Greene. “Most agencies and entities are still siloed–that is, the local hospital is still not necessarily sharing medical records with the dentist office down the block who isn’t sharing them with the primary care provider a mile to the south.”

National database. There is currently no database of U.S. healthcare records, but that reality may be closer than ever. The largest database of patient medical history available today is hosted by Surescripts. The company recently moved into the electronic healthcare records realm when it bought three major electronic health record vendors in May 2015. Greene says that the company’s National Record Locator Service can serve as a model moving forward for patient records in the United States, and the New York Guard has used it during training scenarios.

“Right now some of the situations we are training in, we can already pull a patient’s prescription history from Surescripts’ national data repository. This will speed the process of making sure patients who need medications get them from a point of distribution center, what we call a POD,” he says.

Greene adds that keeping track of who has been administered what medication can prevent black market dealings from popping up in a disaster, in which one person goes around to different PODs to get a prescription pill to sell illegally.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the U.S. military have a comprehensive patient lookup called HealtheForces. This cloud-based tool, which boasts investments of more than $57 million, is the largest health information data exchange and electronic health record platform in U.S. history, according to its website. Greene notes this could serve as a model for the nation moving forward. “From what I’ve seen, the most cost-effective path we could take as a nation would be to let the military health system and the VA create the backbone of a lot of this national record capability,” he says. “And once that backbone is formally set up, everybody interconnects with that. Think of it as the train track. Now everybody else can put their trains on the track.”

Federal roadmap. There are efforts at the federal level to create a one-stop shop for electronic medical records. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) released a draft document last January proposing interoperability of healthcare IT infrastructure, including electronic health records. The first version of the draft, Connecting Health and Care for the Nation: A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap, “outlines the critical actions for different stakeholder groups necessary to help achieve an interoperable health IT ecosystem,” according to the ONC’s website. The roadmap proposes ways for electronic records to be gathered, stored, and shared.

The agency held a public comment period from February to May of 2015 for stakeholders to submit their concerns or suggestions, and several expressed fears about what a nationalized system could mean. For example, the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS) stated that it has “serious concerns about the impact that the Interoperability Roadmap will ultimately have on medical office expenses.” The statement said that “by and large, electronic medical records have increased costs significantly, reduced privacy, and led to some devastating medical errors.”

The AAPS went on to say that “electronic medical records are often riddled with errors, rendering the goal of interoperability one of dubious value, or even harmful. Repetition and reliance on errors is detrimental to patient care.”

Other organizations want a more efficient move toward interoperability than the decade-long plan suggested by the ONC. “We are concerned that a 10-year plan for a learning health system is too prolonged and would leave U.S. health care interoperability behind most other industries and countries,” wrote Michael Jackson, general manager of consumer healthcare, health and life sciences at the Intel Corporation.

Another advocacy group concerned about the ONC roadmap is the Citizens’ Council for Health Freedom (CCHF). Twila Brase, president and cofounder of CCHF, tells Security Management her organization believes that combining the electronic health records of everyone in the United States would hinder individualized patient care. “When you build a national system of all your private healthcare data–which also means mental health data, lifestyle data, genetic data, comments that you make to your doctor–then what you have done is you have infringed upon the confidential doctor-patient relationship. You’ve made the doctor’s office a scary place.”

Brase points out that HIPAA actually provides for the sharing of patient information, meaning that healthcare entities with a “need to know” are able to share that information freely unless state law says otherwise. According to the law, “The health care provider may share or discuss only the information that the person involved needs to know about the patient’s care or payment for care.”

Brase says such language is dangerously vague. “How many people have a ‘need to know,’ and would the patient be happy with all those need to know people having access to their full medical records?”

State initiatives. At the state level, there has been some progress made toward centralizing patient healthcare information. Some have created master patient lookups where providers can access either full patient information or at least a list of who has treated the patient so there is a point of contact. New York, for example, has made progress by incentivizing private and public healthcare companies to aggregate their healthcare information through the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Program, run by the Office of the Medicaid Inspector General.

Emergency care. While the sharing of patient data raises privacy issues, saving patients’ lives is the top priority in an emergency, says Greene. In a disaster situation such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, he notes that medical workers must comply with state laws when dealing with patient medical records.

But there are ways to work around those rules if necessary. Some states have what is known as the “break the glass” procedure, which means that a medical worker can temporarily access a patient record during a disaster. There are also different rules among states for patient privacy, including “opt-in” or “opt-out” procedures. With opt-in, a patient has to give a doctor’s office permission to share his or her medical records with another organization, for example. In an opt-out situation, it’s assumed a patient record is okay to share with other providers unless expressed otherwise.

During a disaster, Greene adds, the ability to not only view, but also edit patient information, is critical. “There has to be a way not only to pull that information from a central repository but also put new information back,” says Greene. “Almost like taking a library book down and then returning it with a few extra pages in it now because it’s the individual patient’s information. And that truly is a challenge.”